The Phillies are a working model of Dave Dombrowski's all-in mentality

Often in the modern game, we hear baseball executives talk about hedging - not trading too much of tomorrow for today. They're usually hesitant to part with top prospects. They talk about wanting to sustain a contention window.

In the expanded playoffs era, and thanks to the randomness of the postseason, many believe it's better to place as many bets as possible - take multiple cracks at the postseason over a longer period rather than go all-in on one season or a short window.

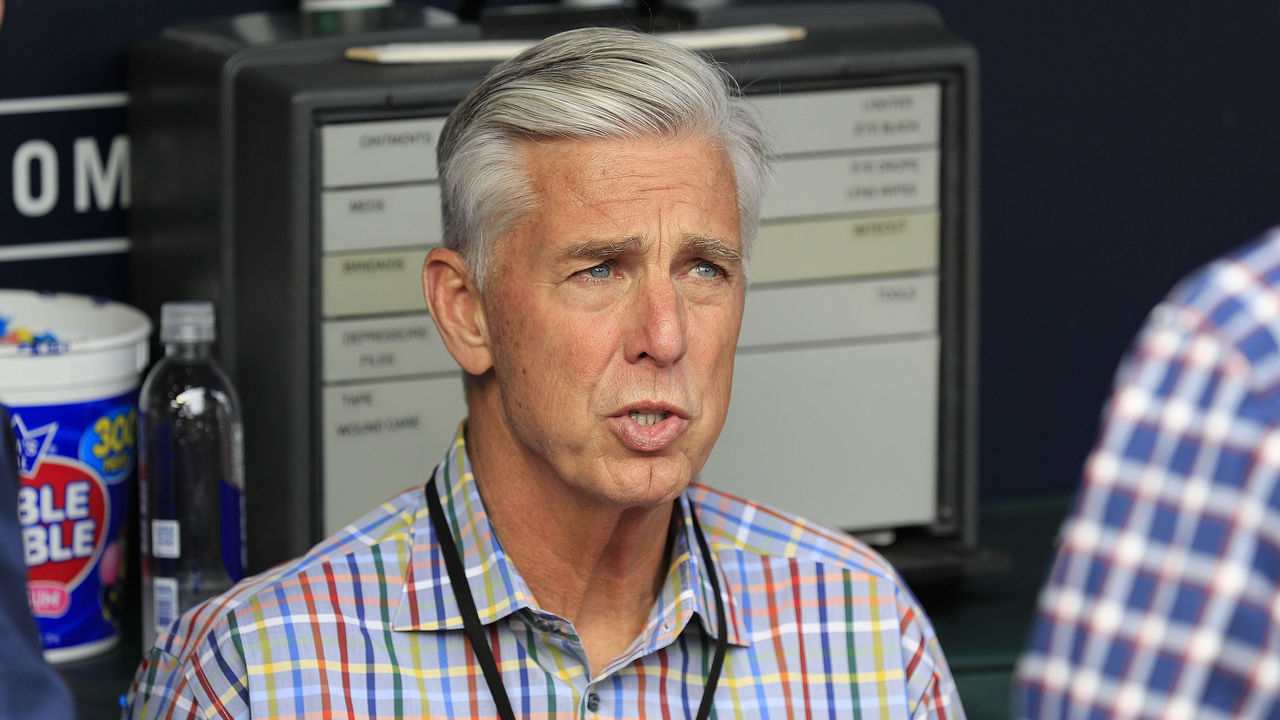

Then there's the approach of Philadelphia Phillies baseball operations chief Dave Dombrowski.

When the Phillies clinched the National League pennant Sunday, they became the fourth team Dombrowski's guided to the World Series. He's won five league championships and two World Series titles: with the Florida Marlins in 1997 and the Boston Red Sox in 2018. Perhaps more executives ought to consider adopting his approach.

Dombrowski owns a reputation for going all-in, for being willing to part with prospects and owners' dollars in trading tomorrow for today. He often invests heavily in proven star talent, particularly two specific types of players: top-of-the-rotation arms and middle-of-the-order sluggers.

How effective is the Dombrowski Way? We explore.

His teams' overall record in the regular season, covering 34 full and partial seasons, is actually slightly below .500 (.492). But it's a better mark than what his respective clubs did in the combined five seasons before he took over as general manager (.479). Interestingly, clubs won at about the same rate in the first five years after he left (.492).

But Dombrowski's best years - when he most heavily bets on a team - are generally when he beats the field. He's taken clubs to the postseason on 10 occasions.

His clubs more often make the postseason than those of the same organizations under the leadership that came before and after him (noting that the Marlins didn't exist before Dombrowski became their expansion GM.) The five organizations have only two playoff berths: The 2013 Red Sox won a title in the five-year window before Dombrowski arrived, and the 2003 Marlins won a World Series a few years after the infamous fire sale that followed their 1997 title under Dombrowski.

While Dombrowski's overall wins and losses may appear middling, his best years have been very productive and generally better than what preceded and followed.

His all-in approach helps lift teams to the top of the game. Perhaps he builds teams that are better suited for October, like this year's Phillies.

The 1997 Marlins won 92 regular-season games and the World Series, becoming the first wild-card team to do so.

As a team's top baseball executive, Dombrowski's built only eight teams that won 90 or more games. But his teams that do advance to October generally don't exit early.

The only team he built that won more than 95 games was the 2018 Red Sox (108 wins), which won the World Series over the Dodgers.

Dombrowski's first stop was with the Montreal Expos, taking over as GM at age 31 in the middle of the 1988 season. He was an outlier in the GM chair, the youngest in the game at the time before it became standard practice for young, Ivy League-educated executives to be hired for those jobs in the post-"Moneyball" world.

Montreal is the only club he didn't take to the postseason. He left to lead the expansion Marlins more than a year before they took the field in 1993. But as GM, and previously as Expos director of player development, he played a role in developing what became one of the game's best farm systems in the early and mid-1990s.

His reputation as an aggressive trader began up north, and it's where he had one of his greatest misses: trading for Mark Langston, a quality pitcher and soon-to-be free agent, by surrendering a package that included future 300-game winner and Hall of Famer Randy Johnson. The trade happened in late May and Langston was spectacular in 24 starts, earning a 2.39 ERA and 4.9 bWAR, but Montreal finished 81-81. Langston signed with the Angels that winter.

Dombrowski didn't stop going big, though.

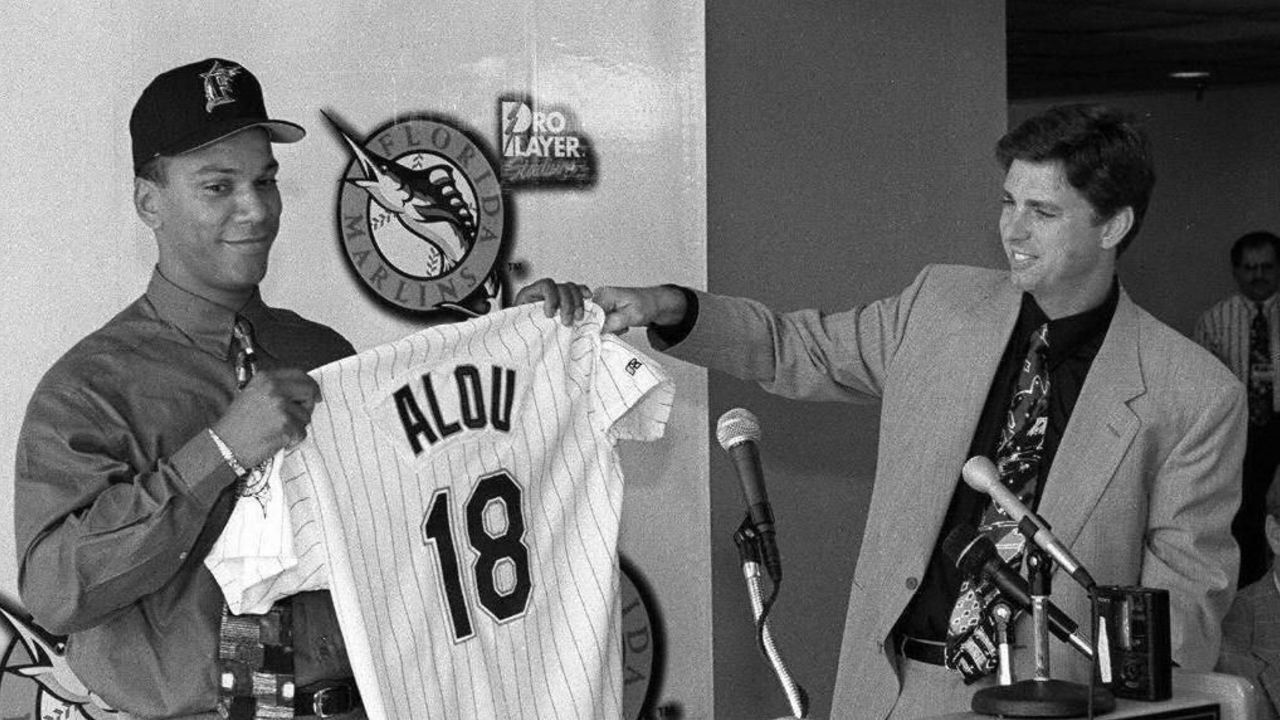

He made a deal to acquire Gary Sheffield with the Marlins in 1993, and signed pitchers Kevin Brown, Alex Fernandez, and Al Leiter, and outfielder Moises Alou in free agency. His spending spree in the winter of 1996 - $89 million for six players - was a record at the time. It was supplemented with homegrown talent like shortstop Edgar Renteria and catcher Charles Johnson, and outfielder Jeff Conine via the expansion draft.

The Tigers' two World Series teams were built around big-ticket players, too: acquiring Carlos Guillen, Miguel Cabrera, and Max Scherzer via trade; scooping Ivan Rodriguez, Kenny Rogers, Magglio Ordonez, and Victor Martinez in free agency; and landing power ace Justin Verlander with the second overall pick in 2004. The Tigers also added big-dollar signings who had initial impact but didn't always age well, like Prince Fielder. (Dombrowski did manage to peddle Fielder's contract to Texas for Ian Kinsler.)

The Tigers hit bottom early in Dombrowski's tenure, losing 119 games in 2003, his second season at the helm. But Detroit was in the World Series by 2006 thanks to Rodriguez, Guillen, Ordonez, Rogers, Verlander, and Curtis Granderson, a third-round pick in Dombrowski's first Tigers draft in 2002.

Dombrowski displays a willingness to emphasize offense over defense, like he did when the Tigers moved Cabrera back to third base to accommodate Fielder in 2012, the last time Detroit went to the World Series. And like this year's Phillies.

By Defensive Runs Saved, the 2022 Phillies ranked 25th in the majors (minus-35), and the 2012 Tigers ranked 24th (minus-29). The 1997 Marlins also ranked below average, according to the more limited advanced defensive metrics available at the time. However, the 2018 Red Sox were in the middle of the pack defensively and the 2006 Tigers ranked as an excellent defensive team.

A more common thread is Dombrowski's preference for high-end talent, especially with a focus on top-of-the line aces and sluggers.

San Francisco Giants pitching director Brian Bannister, who worked under Dombrowski, shared recently what he feels makes Dombrowski a great executive. One factor is that Dombrowski is willing to pay the price for elite talent, even if those deals are portrayed publicly as overpayments.

3. He believes in blue chip players.

— Brian Bannister (@RealBanny) October 23, 2022

In today’s analytical game, it’s often about who “wins” the trade or $/WAR or other internal valuation metrics.

Baseball teams have become very smart.

But this can lead to a lack of trade liquidity.

Wrote Bannister: "By always waiting patiently for 'smart' trades or avoiding larger free-agent contracts, it admittedly reduces career risk and public scrutiny. But by being willing to lose a trade slightly at times from a valuation perspective, it often gives you access to special players.

"Dave believes that players with a proven track record have special qualities and will rise to the occasion. Especially in the postseason. This occurred when (Boston) won the World Series in 2018 and it’s occurring for the Phillies right now."

Of course, you have to have ownership's commitment to acquire such players. Four of the five clubs Dombrowski built that reached the postseason ranked in the top seven of Opening Day payroll, according to data at Baseball Cube.

That's the kind of strategy that might play especially well in October, when the game is different.

Aces take on a greater share of postseason innings than they do in the regular season, and home runs account for a greater portion of scoring. Behind a pair of aces in Zack Wheeler and Aaron Nola, and sluggers Kyle Schwarber, Bryce Harper, and Rhys Hoskins, the Phillies went from being the last team to make the NL playoff field to the last one standing.

Yes, the only player Dombrowski acquired in that aforementioned group was Schwarber, but outsiders thought it was foolhardy to put him in left field opposite the equally defensively challenged Nick Castellanos in right. Dombrowski otherwise didn't have to do as much building with this pennant winner as in previous stops. He added Jose Alvarado and Brandon Marsh in trades. Some young players took steps forward under a player-development process that was overhauled by the previous regime.

Perhaps Dombrowski's most important decision this year was changing managers mid-season, removing Joe Girardi after a 22-29 start and replacing him with Rob Thomson. It's hard to measure, but past associates like Bannister say Dombrowski possesses an excellent feel for his clubs.

Yet, for all his success, he's also been fired twice as an executive, and certainly left some franchise cupboards more barren than when he took over.

Remarkably in September 2019, less than a year after leading the Red Sox to a World Series title, he was out in Boston. It was a year in which the club underachieved, with contracts like Chris Sale's and David Price's looking like they were underwater. The club's farm system was ranked 25th by MLB Pipeline, down from No. 2 in 2015 when Dombrowski arrived.

He was dismissed in Detroit in 2015 after the club's talent pipeline ran dry. The Tigers are still struggling today and haven't had a winning season since 2016, although Dombrowski's successor, Alex Avila, shares in that blame. Since 2015, the Tigers have lost more games than every team except Baltimore.

Perhaps Dombrowski is more of a builder than a sustainer, but flags fly forever. If he can raise one more this October in Philadelphia, the fan base will certainly believe in his method.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.