The Brewer Way: How Milwaukee became a World Series contender

In the winter before the pandemic arrived, Corbin Burnes was trying to get better. He had to. He posted an 8.82 ERA in 2019, one of the worst marks in the majors. So he went out to the synthetic turf mound in the backyard of his suburban Phoenix home looking for a fix. He threw ball after ball into the netting behind the makeshift plate, experimenting with grips. His wife helped collect the baseballs that accumulated on the ground.

Even though the Milwaukee Brewers' state-of-the-art pitching lab at the club's new spring training complex was just a few miles from his house, he didn't spend much time there. His self-help quest wasn't driven by spin-tracking data or high-speed camera images. His backyard bullpen offered a low-tech feedback loop, guided by what he felt and saw. What felt right, what he created, was not the slider he intended to throw.

Initially, he sought a pitch in the "88-90 mph range," Burnes told theScore, but as he kept working on it, as he kept throwing it, its velocity kept increasing. The pitch became a mid-to-upper 90s blur of late-breaking filth that seemed impossible to make quality contact against. What he built is a unicorn pitch. The offering is akin to Kenley Jansen's peak cutter, only Burnes is, of course, a starting pitcher.

"When we came back to summer camp, it was kinda like, 'Whoa, you got something here,'" Burnes said.

Corbin Burnes: Cutter and Slider grips. pic.twitter.com/kLpn4yyJSq

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) April 14, 2021

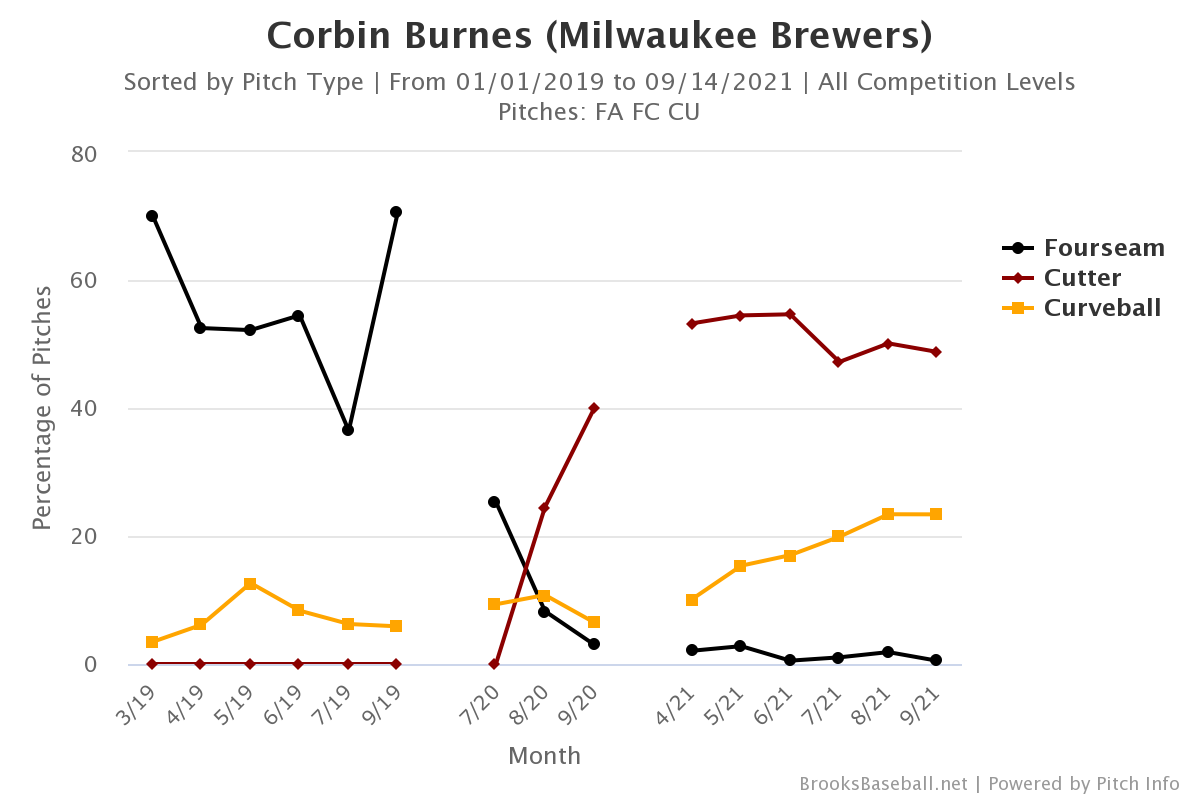

Last season, Burnes stopped throwing his four-seam fastball and replaced much of that usage with his cutter. He was the most improved pitcher in baseball in 2020. Burnes was even better early this season and - incredibly - he's kept improving even as baseball cracked down on sticky stuff and he suffered some spin decline.

Burnes has a 2.10 ERA and .193 opponents batting average in the second half of the season, compared to a 2.36 and .210 in the first half. He's gotten better because he keeps evolving. He's spread apart his fingers on his cutter grip this year, which added velocity to it, and now enjoys above-average vertical movement - what appears as a rising effect to batters - and above-average horizontal movement on it.

Surprised I didn't notice this earlier, but I think Corbin Burnes has separated his fingers on his cutter grip this year. Could be the reason behind the vertical movement gain.

— Lance Brozdowski (@LanceBroz) April 14, 2021

Shape more like 4S than slider = Grip more like 4S than slider. #Brewers pic.twitter.com/CDB3x2Lb9q

Burnes further expanded his skill set by increasing his curveball usage as this season went along. His hammer curve grades even better than his cutter, as opponents are hitting only .073 against it. He used it to throw eight no-hit innings Saturday in Cleveland, combining with Josh Hader for the ninth no-hitter in the majors this season. After never throwing the curve more than 8% of the time in a previous season, he's thrown it on about a quarter of his offerings in the second half.

"The curveball is more something I picked up this year. We found this year that I was able to throw it with a little more effectiveness," Burnes said of his work with the Brewers staff. "It provides a good speed differential off of the sinker and cutter. Kind of plays if a right- or left-handed batter is in there."

Brewers bullpen coach Steve Karsay, who's watched the evolution of Burnes and his pitch arsenal from his time in the bullpen to his struggles in 2019 to his breakout season, said: "I mean, really, the only comp I can think of is (Jacob) deGrom."

Like deGrom, Burnes is one of the few individual pitchers on the planet to feature four above-average pitches per FanGraphs' run values and premium velocity. Burnes now has five when including his curveball.

Burnes' remarkable pivot is a big reason why the Brewers have become a threat to win it all.

The "Oriole Way" and "Cardinal Way" celebrated standardized, top-down player development processes during those organizations' heydays. If there is a "Brewers' Way" - an organizational belief system that explains how this small-market club became a World Series contender - it's not a one-size-fits-all philosophy but tailored toward individuals instead. The Brewers have built upon player strengths and added skills that complement them. It's a story about continuous improvement, ideally driven by the player. While a lot of teams are focused on this in the data-driven age of player development, the Brewers are executing better than most.

For instance: Burnes, Brandon Woodruff, and Freddy Peralta each rank among the top 27 starting pitchers in WAR gains since 2019.

When veteran Brewers pitcher Brett Anderson came up through the Arizona Diamondbacks organization, he said coaches and club officials wanted everyone to try and throw like then-Diamondbacks ace Brandon Webb. The problem, of course, was no one could throw a sinker like Webb.

"They don't try to pigeonhole guys or change them one way or the other," Anderson said of the Brewers' methods. "We have sinker guys, four-seam-up guys, cutter guys, it's working with our strengths and going from there."

The Brewers' road map to a title begins with a special rotation, but the improvement stories and the collaborations between self-help efforts and targeted instruction exist all over the roster, which might be the most complete in the game.

When Milwaukee acquired Willy Adames on May 21, it became perhaps the most symbiotic transaction of 2021.

Once a promising prospect, Adames was struggling in Tampa Bay. He hit .197 with the Rays this season and struck out in 36% of his at-bats. He was seemingly chasing every breaking ball that fell below the strike zone. The Rays traded him to Milwaukee with reliever Trevor Richards for pitchers J.P. Feyereisen and Drew Rasmussen.

Behind Adames in the Rays organization was baseball's No. 1 prospect, Wander Franco, also a shortstop. It's fair to wonder if Franco's shadow led Adames to press early this season, although Adames said that wasn't the case because the Rays constantly move players around the field. By late spring, though, the amiable Adames was tired of the questions about Franco. The two are close and Adames considers himself a mentor to Franco.

"Every time I was doing an interview it was the same question, 'Are you worried about Wander coming up?' It was kind of annoying after a while," Adames told theScore. "I was at the point where I had to say the same answer for everybody."

When he arrived in the visiting clubhouse in Cincinnati on May 22 for his first game as a Brewer, that question disappeared. Brewers hitting coach Andy Haines pulled him aside in the indoor batting cages in the depths of the stadium. Here was a chance to reset.

Haines, seated next to Adames, arranged two laptops before them: one featured video of Adames in 2019, his best year, and the other showed video of some poor swings from earlier in the season. The Brewers did their homework on Adames; they knew he was a premium athlete, a plus runner, and a quality defensive shortstop. He'd demonstrated above-average hard-hit ability when he connected with a pitch - the problem was that wasn't happening often enough.

Haines wanted to know why Adames changed his swing.

Adames explained that his struggles became pronounced in the postseason last year when the Rays advanced to the World Series. In the fifth inning of Game 1 against the Dodgers, Mookie Betts walked and stole second base, meeting Adames at the bag.

They were amiable division rivals during Betts' time with Boston. Betts had watched Adames struggle in the playoffs. So, in the middle of the game, between pitches at Globe Life Field, at second base, Betts said he might be able to help him.

"He came up randomly and told me that he had the perfect guy to help me get to the next level. I was so surprised," Adames said.

After the game, Adames sent Betts his cell number through an Instagram message and Betts responded with a text and a name to call: Lorenzo Garmendia, private hitting instructor to Betts and a number of pros.

After the Dodgers beat the Rays, Adames made the trip to Miami to begin working with Garmendia. He developed a new routine that included one-handed drills, using a new customized bat, and countless reps against high-velocity pitching machines. The idea was to better unlock his power and hit the ball harder and in the air more often, like Betts had done.

Adames brought his new swing and his new approach into the season. Initially, it didn't work.

Haines listened to the story and what Adames was trying to accomplish. The coach didn't suggest making wholesale changes to Adames' new swing or routine.

"The one-hand drill, the bat that (Garmendia) gave me … hitting off the machine a lot, that's what we were doing in Miami every day," Adames said. "I am still doing the same routine."

Haines suggested one tweak, however: get more upright in his stance like he'd been in 2019.

Adames kept the routine he learned in Miami, as well as the swing path and leg kick. What he changed was his posture. When he begins his swing he starts with his back upright.

"I just try to ask the right questions to get to where I think we should probably get to," Haines said. "Empowering him to see the information, but talk us through how he got here."

Almost immediately, Adames became a different player in Milwaukee. He stopped chasing as much and cut his strikeout rate dramatically. He was hitting .294 with the Brewers before landing on the IL this month with a quad strain. Adames said he expects to be back next week. Hidden amid his contact issues in Tampa this season were improved power-per-contact numbers. He produced a career-best hard-hit rate of 44.5%, which Adames believes is a product of his new swing. That carried over to Milwaukee (45.2%). What's changed is he was making more contact after adjusting his stance.

"(Haines) helped me be taller at the plate," Adames said. "That helps me to see the pitch better, and recognize the pitch better."

If there's a "Brewers' Way," perhaps it shows up here: the club didn't pressure Adames to make dramatic changes. They believe he was correct in trying to unlock his power and he's transitioned from a ground-ball hitter to a fly-ball hitter this year - increasing his fly-ball rate to 40% from 31%. Rather, they collaborated to make slight adjustments. Like with Burnes, the impetus to improve started with the player.

And as much as Adames needed the Brewers, the Brewers needed him.

Since the club acquired Adames in late May, Milwaukee boasts a different - and far more prolific - offense. The Brewers ranked 12th in the NL in runs scored and tied for 26th in the majors through May 21, but rank first in the NL in the second half and fourth in the majors since the trade.

Adames improved his hitting while playing a premium, up-the-middle position. Improving in the center of the field with players who can contribute on both sides of the ball gives the Brewers an edge. And there, in the middle of the field, Adames isn't alone in growth.

The Brewers were interested in signing Kolten Wong last winter in part because of his excellent glove. They also signed Jackie Bradley Jr. in the offseason to bolster their outfield defense.

Milwaukee doesn't just have an elite pitching staff and improving lineup; they also have the game's best defense, according to FanGraphs' defensive metric, and rank third in Ultimate Zone Rating and fifth in Defensive Runs Saved. Wong's a big part of that.

While his glove has rarely slumped, it's his improvement offensively that has led to Wong's bounce-back season. He's another Brewer who was focused on fixing a weakness.

When Wong's $12.5-million option was declined by the Cardinals last October, it was something of a jolt. He felt he had to get more out of his bat. He hit one home run in 208 plate appearances last year and had one of his poorer offensive seasons.

So late last fall, he dove into his numbers, using public databases on the internet to see if he could identify an area to improve, a weakness that wasn't obvious. He always believed in a contact-focused, two-strike approach. He was coached to believe in that since his youth, and owns a below-average strikeout rate for his career as a result. What he found, though, is that his two-strike approach and his consistent efforts to trade power for contact was actually hurting him.

"I started to realize that my swing-and-miss rates were pretty similar regardless if I was going to no leg kick or just trying to put the ball in play," Wong said. "This year when I got to two strikes, I decided I was not going to shorten up."

The results: Wong's slugging percentage with two strikes is up by nearly 100 points. His overall slugging percentage (.464) is a career high. While his swing-and-miss rate is up slightly, his power gains have more than made the trade-off worth it - he's on the cusp of his second 3 WAR season. By weighted runs created plus, he's having the best hitting season of his career (115). He's made the two-year, $18-million contract he signed a major bargain for the club.

And what honed Wong's new approach even further was one of Haines' most frequent messages, albeit one of his rare one-size-fits-all beliefs: Be aggressive, but stay within the strike zone. Instead of flailing at pitches off the plate with two strikes, Wong tried to tighten his zone discipline with two strikes.

Haines periodically gives reports to position players, grading their swing decisions and zone discipline.

"It's just kind of our process and how we go about continuous improvement," Haines said. "I think that's what an MLB season is. You have to use the length of the season to help you, not hurt you. I'm a big believer in that.

"We feel like as we continue to show our guys quality information, more predictive (metrics), how they are getting to their outcomes … (results) will show up over time. … We're making sure they value the correct things."

Through May 21, the Brewers had a 26.3% strikeout rate as a team, above the MLB average through that date (24.1%). Since then, it's dropped to 23.1% - below the MLB average of 23.3% for that period. Compared to last year, there are four Brewers who rank in the top 76 of WAR gainers, year over year, in the majors: Adames, Wong, Omar Narvaez (who also works with Garmendia), and Luis Urias.

Yes, Milwaukee's also had some notable decliners, such as Bradley Jr. and Keston Hiura, and injuries have perhaps sapped Christian Yelich's power, but the pitching-first Brewers are on pace for their fourth-best position player WAR season since 2011 - coupled with what is already their best pitching season in franchise history by WAR.

Manager Craig Counsell said he feels his players are more and more buying into the notion of the "circular" nature of a batting order, wearing down opponents through quality at-bats.

"We're not a big home-run team," Counsell said. "But the quality of at-bats we get throughout a game. … That's what's helped us score runs at times. We make it really tough on guys and maybe there's a crack somewhere."

On the surface, the role of Brewers' bullpen coach seems like one of the least eventful jobs in baseball for the first five or so innings of a game. The phone rarely rings that early - a Brewers starting pitcher is often shoving. So what does Karsay do out there early in games?

"We watch the game. We have our iPads out there. We'll talk about our sequences, and what happened in yesterday's game for the guys that pitched," Karsay said. "By the fourth, fifth inning, guys start to get locked in."

Karsay represents much of what a club wants in a coach. He was a major-league player who dealt with highs and lows that included Tommy John surgery. He owns that experience, but he's also taught himself how to use new available tools. He's one of the coaches who keeps an eye on any changes to pitchers' release-point data and quality-of-stuff metrics to make sure there are no "red flags."

He said the Brewers' individualized approach is especially important in the bullpen, where games become matchup-based in the later innings.

"The biggest challenge is to treat each guy as an individual," Karsay said. "They are all puzzle pieces that you have to piece together to make a bullpen work as efficiently as possible."

Here, too, the Brewers keep improving. Consider the case of Devin Williams, Karsay said, who burst on the season last year as a dominant back-end arm along with Josh Hader. Williams is still evolving and keeps improving one of the best pitches in baseball: his changeup.

"His changeup is something special," Karsay said. "He's had it his whole life. But he's refined it more. … It's him learning how to use his fastball with it in combination, to move his changeup to both sides of the plate, not get too heavy with it."

Like so many of his teammates, Hader, an All-Star, is getting better, too: his ERA and fastball velocity in 2021 are career bests.

The Brewers look like a legit World Series threat as the playoffs near. They'll make the long season work for them, using its length to keep improving, to keep getting better.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.

HEADLINES

- Red Sox star Devers leaves game with knee discomfort

- Phillies' Suárez dazzles in complete-game shutout over Rockies

- Mets overcome Pirates, Jones for 9th win in 12 games

- J-Rod downplays slow start: 'I will never stress so much' so early

- Cora laments Casas' failed steal attempt: 'There's no excuse, he knows it'