Saying the quiet part loud: Owners' greed defined baseball in the 2010s

The Modern Era Committee, one of the National Baseball Hall of Fame's four auxiliary voting bodies, rectified a longstanding injustice when it posthumously elected Marvin Miller to Cooperstown earlier in December. Miller, as it happens, wanted nothing to do with the Hall of Fame, expressing in 2008 his desire to be removed from future consideration after being denied enshrinement for the third time, but the recognition was nevertheless overdue.

No individual did more to revolutionize the economics of baseball. As first executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, Miller negotiated the game's first collective bargaining agreement, helped end the reserve clause (thereby giving birth to free agency), and paved the way for players to enrich themselves - not merely their team's owners - off their own talents.

Ironically, Miller's election to the Hall of Fame comes at a time when baseball, as a collective corporate entity, is being particularly transparent in its efforts to denude players of the earning power that Miller's work afforded them.

In 2019, the average major-league salary dropped for an unprecedented second straight year, even as revenues continued to soar. The year prior, league revenues totalled $10.3 billion, according to Forbes, setting a new gross revenue record for a 16th consecutive season. Meanwhile, the league's poorest franchise was recently valued at $1 billion. Yet, the players' share of that wealth - the wealth they generate - continues to dwindle. Over the last half-decade, player salaries have comprised a smaller and smaller percentage of total revenues, peaking at 57.3% in 2015 and falling to 54.2% by 2018, per Forbes. While that may not seem significant, 3% of league revenues in 2018 equated to $309 million.

Owners are increasingly comfortable pocketing more of the money pouring into the game, and their front-office lackeys are getting increasingly creative in facilitating it. In the interest of "sustainability" or "flexibility" or other such euphemisms, baseball executives resort to all kinds of bad-faith maneuvering to keep salaries down, from manipulating the service time of top prospects to avoiding the free-agent market to opting not to tender contracts to perfectly fine arbitration-eligible players.

"We're very concerned," Boston Red Sox slugger J.D. Martinez told USA Today in July. "It's been a little lopsided the last couple of years, and I know the association definitely wants to do something about it."

"The players are very cognizant what's going on with economic situations because it's not just affecting the peripheral players," added Washington Nationals ace Max Scherzer. "It's affecting every player."

And as baseball's owners bathe in tubs filled with cash, luxuriating in unprecedented economic prosperity, their response to their discontented labor force amounts to little more than a shrug.

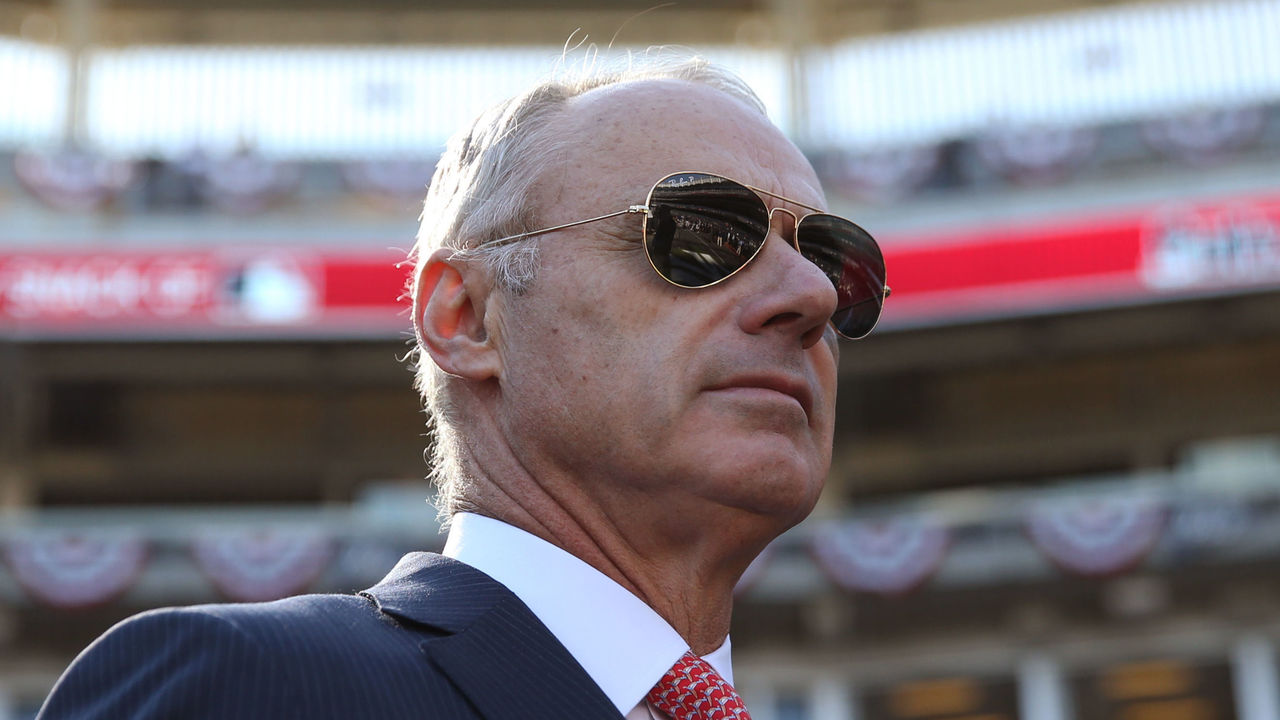

"Maybe Marvin Miller's financial system doesn't work anymore," commissioner Rob Manfred told MLBPA representatives this summer, according to Craig Calcaterra of NBC Sports.

The mounting frustration among the players, however, is merely a symptom of the corporate greed that defined the last decade in baseball, a widespread and naked commitment to maximizing profits that has created the possibility of a labor stoppage when the current CBA expires two Decembers from now. Baseball fans don't need a strike or a lockout to appreciate the extent of the owners' collective avarice, though. They already know.

Since 2012, the first year of the expanded wild-card era, Major League Baseball's attendance numbers have dropped roughly 8.5%, tumbling in each of the last seven seasons. This year, the league saw its worst attendance numbers since 2003, when the United States was still wresting itself out of a recession, with only 68,494,895 fans pouring through the turnstiles in 2019. It's not hard to see why.

Four teams lost 100 games or more this year, tying the dubious record set in 2002, while three clubs won at least 100 games. It's evidence of a competitive crisis that has, along with the increasing cost of attending a Major League Baseball game, alienated fans. But it's not the successes of the Chicago Cubs and Houston Astros - moribund franchises transformed into juggernauts by tanking, or being deliberately bad for an extended period of time for the sake of sustained future success at the big-league level - that sucked the competitiveness out of the game. It's greed.

Historically, fielding a competitive team was the best way to ensure big profits. Before the days of cable television and streaming services, team owners needed butts in seats to make money, and the best way to get said butts in said seats was by winning baseball games. That's not the case anymore.

Increasingly lucrative local and national television contracts, along with the league's recent sale of a majority stake in its digital media spinoff, BAMTech, for $2.6 billion, has kept teams rolling in money irrespective of wins and losses; in 2018, for instance, the Kansas City Royals (and every team) received a one-time payout of more than $50 million from the BAMTech sale, about $20 million from their local TV rights-holder, and roughly $50 million from the league's central fund (comprised of revenues from national broadcast rights, licensing, and sponsorship). In other words, had the Royals gone 0-162 and played in front of an empty stadium every night, they still would've made about $120 million in revenue in 2018. (And the Royals have one of the league's least lucrative local TV deals.)

Teams don't need to be good to make money. So, increasingly, they don't try to be. And fans, as a result, aren't showing up. While multiple factors contribute to waning attendance numbers, they nevertheless seem to be indicative of a broader disillusionment with baseball: This year's World Series drew fewer than 14 million total viewers, according to Variety, making it the least watched Fall Classic in five years.

"We have some of the most remarkably talented players our game has seen as a whole in a long time," MLBPA head Tony Clark told the Associated Press in September. "But the willful failure of too many franchises to field competitive teams and put their best players on the field is unquestionably hurting our industry."

As Clark intimated, though, the problem extends beyond tanking. In a climate where contending is optional, every team, regardless of financial stature or the state of its roster, has been emboldened to prioritize the bottom line over the product on the field. In some cases, owners and front-office types don't even try to hide it, unfazed about saying the quiet part loud.

When asked last spring what advice he would give fans growing uneasy about Francisco Lindor's uncertain long-term future in Cleveland, Indians owner Paul Dolan didn't so much as pretend he was interested in signing the beloved All-Star shortstop to an extension that would keep him with the franchise beyond his arbitration years. "Enjoy him," Dolan told Zack Meisel of The Athletic. "We control him for three more years. Enjoy him and then we’ll see what happens." Less than a year later, the Indians - despite finishing 93-69 in 2019 - seem all but guaranteed to unload Lindor as part of a broader effort to cut payroll; earlier in December, the Indians traded longtime ace and two-time Cy Young award winner Corey Kluber to Texas in what amounted to a salary dump.

Meanwhile, even with the makings of a fine team in place, the Chicago Cubs are currently trying to trade away one of their best players, former National League MVP Kris Bryant, in a naked attempt to slash expenses for 2020. Despite being valued at $3.1 billion earlier this year, the Cubs have spent the nascent offseason crying poverty, just as they did last winter, and have reportedly been telling player agents that they need to clear out payroll before engaging in serious negotiations.

They're not the only financial juggernaut more preoccupied with cutting costs than winning a World Series, though. After opting not to spring for Bryce Harper or re-sign Manny Machado last winter in an obvious effort to get under the luxury-tax threshold of $206 million, the Los Angeles Dodgers - who haven't won a World Series since 1988 and were recently pegged as the 10th-most valuable franchise in all of professional sports ($3.3 billion) - don't seem inclined to make a meaningful addition this winter either, even with their projected 2020 payroll sitting at just over $170 million, according to Cot's. Despite the Dodgers' ostensible interest in top free agents Gerrit Cole and Anthony Rendon, they didn't land either of them, and now most of the market's impact talent has signed elsewhere.

In short, a bunch of teams aren't trying at all, while many teams that are trying to be competitive are only doing so insofar as their profit margins aren't compromised and their books aren't bogged down with potentially onerous long-term commitments. Baseball, over the last decade, became an asset-management industry in which winning a World Series was more incidental than essential.

And while the owners' singleminded pursuit of profit has left players disgruntled and fans disinterested at the major-league level, their greed now threatens to decimate the minor leagues as well.

With their current operating agreement set to expire less than a year from now, Major League Baseball recently submitted a devastating proposal to Minor League Baseball, tabling a radical restructuring of the lower levels of the minors that would effectively destroy 42 of the game's 160 affiliates. Again, there's no mystery as to why.

"For us, minor-league baseball is not a moneymaker," one general manager recently told Yahoo's Tim Brown. "There's no profit. The return is generating major-league players. We'd do it better in smaller classes, with more teachers."

Under this proposal, which has spawned a public feud between MLB and MiLB, local economies would be upended, and baseball fans in non-major-league cities across the country would potentially lose access to professional baseball. The callousness of the scheme elicited a response from presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, who expressed his outrage in a series of letters to Manfred.

"Let's be clear," Sanders wrote in his first letter. "Your proposal to slash the number of minor-league teams has nothing to do with what is good for baseball, but it has everything to do with greed."

You won't find a better snapshot of the state of baseball as the decade comes to a close: The owners' greed has metastasized to the point that a presidential candidate with significantly bigger fish to fry - 10 months into a grueling campaign and fresh off a heart attack - couldn't help but call it out.

It's tempting, of course, to see the current thawing of the free-agent market as a step in the right direction. Virtually every major free agent was off the board well before Christmas, while spring training was underway when Machado and Harper finally signed. Stephen Strasburg and then Cole received record-breaking contracts that hint at a possible market correction. But Harper and Mike Trout ultimately got record-breaking deals last winter, too, and salaries still went down overall. Competition still lagged. And the underlying system remains unchanged.

So long as it does, greed will be the central organizing principle throughout the league. And it certainly doesn't sound like Major League Baseball is inclined to entertain radical changes to that system - one that doesn't sufficiently incentivize teams to contend, nor allow players to capitalize on their earning power at the height of their talents - in the upcoming CBA negotiations.

"(There's) not going to be a deal where we pay you in economics to get labor peace," Manfred said in his summer meeting with MLBPA reps.

Brace yourselves, in other words, for the game's first work stoppage in more than a quarter-century. It's coming. The powers that be, through their increasingly reprehensible machinations over the last decade, have left the players no choice but to strike.

You don't have to be Marvin Miller to see that.

Jonah Birenbaum is theScore's senior MLB writer. He steams a good ham. You can find him on Twitter @birenball.