Week 2 Film Study: Surging Stanford dominates third-down battle vs. USC

Here's a look at some of the more intriguing film-related developments from Week 2 of the college football season:

USC-Stanford: A battle of third-down pressure schemes

Games between good teams often come down to which side performs best on third downs.

USC-Stanford was no different, with the so-called money down living up to its reputation. Each team entered with different third-down plans, and the Cardinal executed, but the Trojans didn’t.

Stanford came after JT Daniels. The true freshman quarterback was a millisecond slow on everything, including his processing, decisions, and throws.

Typically, freshman quarterbacks struggle to diagnose what’s happening on the back end when defensive coordinators get fancy and show one thing pre-snap, then morph to another look post-snap. Stanford indulged in no such wizardry. Its defensive backs played man coverage across the board, daring Daniels to beat them.

The fun took place up front. Stanford defensive coordinator Duane Akina threw every kind of man blitz you can imagine at Daniels from all sorts of formations. Linebackers, defensive backs, and edge defenders crisscrossed at the line of scrimmage. USC’s offensive line struggled to pick up who was coming and from where.

Man blitzes are easier for quarterbacks to attack. If the defense sends an extra pass-rusher there’s one less defender in coverage, so either someone is open, or there are one-on-one matchups all over the field.

Quarterbacks have to get the ball out quickly, and Daniels couldn't as Stanford stunned him early by looping its linebackers and attacking up the gut. The Cardinal dropped a safety into a “robber” spot in the middle of the field, a low-hole defender who reads the eyes of the quarterback and attacks the ball:

Daniels failed to adjust and didn't speed up his internal clock. Above, he was a tick slow on his read and throw. His pass should have been intercepted.

Akina relented a couple times, and Daniels was much more productive when Stanford rushed just four:

The young Trojans quarterback has a knack for climbing through and then escaping the pocket, rather than spinning out and bailing as quick as possible. That’s a veteran move, and he also does a nice job of keeping his eyes downfield while looking for receivers to uncover, instead of dropping his sight line and charging toward the first down.

Akina’s defense handed the road map to USC’s opponents for the foreseeable future. Until Daniels proves he can take on the blitz, the Trojans' offense is going to be in trouble. Basic single-man blitzes (often called a "green dog," meaning that if your man stays in to protect, blitz!) torpedoed USC’s third-down attack:

It was different and baffling on the other side of the ball. USC’s brain trust opted to play its DBs further back, using a mix of combo-zone and off-man coverages. They still sent pressure, but the blitzes were zone pressures, dropping a defensive lineman into coverage and bringing a blitzer from a different spot.

Stanford’s K.J. Costello is a decent quarterback. He’s fine for an offense built on its ground game, with a big arm and the ability to stretch the field. But he’s not a precise thrower.

Costello is a rhythm thrower. He wants to hit his back foot and get the ball out. A defensive coordinator's job is to break that rhythm by throwing off the timing of routes with press coverage, or moving the QB off his spot.

USC opted for neither, particularly on third-and-long, which is a cardinal sin. Costello was allowed to sit back, survey the landscape, and look for open receivers. As long as his receivers found the soft spots in zones, the Stanford offense was in business.

Spoiler: they did.

Costello closed the first half with a five-play, 51-yard touchdown drive, marching his unit down the field in an efficient two-minute drill. Every throw he completed was against soft, off-man coverage, and it was too easy.

USC’s staff blew this one.

Laviska Shenault: holy moly!

Laviska Shenault was easily the best player on the field for Colorado’s rivalry win over Nebraska. After putting up 212 yards on 11 receptions with a touchdown in Week 1 against Colorado State, he posted 185 all-purpose yards with two touchdowns on Saturday.

Shenault is the complete package, with the size to shake press coverage, the sudden quickness to beat cornerbacks at the stem of his route or in the open field, the length and intuition to create early and late separation, and the innate ability to contort his body in the air.

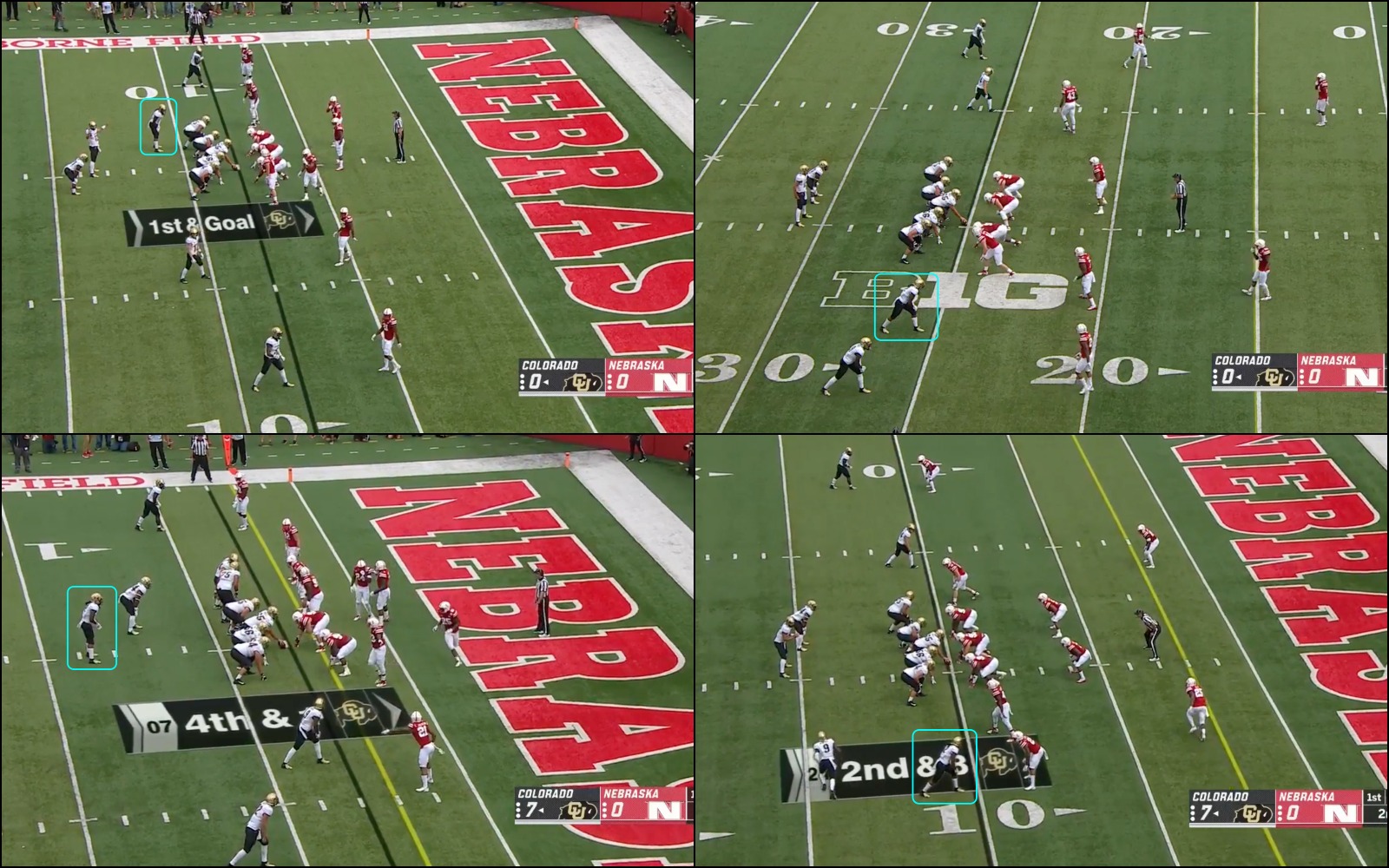

That was all on display Saturday. His back-breaking, game-winning touchdown was the best example:

Sheanult was in the slot, and Nebraska had its slot corner in press coverage. The corner seemed nervous to get his hands on the receiver, perhaps knowing Shenault has the length, agility, and slippery hips to blow by him.

Instead, the corner played the leverage game, not attempting to jam or re-route Shenault. He played with inside technique while shepherding Shenault toward the sideline, knowing that would make the throw more difficult.

Shenault quickly exposed that mistake when he created instant separation, hitting the corner with a stutter step.

Against press, Shenault would normally have to give the cornerback less access to his midsection. But the corner didn’t bump him, so he was able to get a free release from the line and gallop to full speed untouched. Colorado quarterback Steven Montez hit Shenault with a fantastic throw.

How Mike MacIntyre’s team uses the sophomore is interesting. He flexes right across the offensive formation, aligning anywhere and everywhere. At any point, he could be in the backfield as a wildcat quarterback, offset as a wing, lined up on the boundary, or in the slot.

He’s effective from anywhere, showing good patience as a runner - allowing his blocks to develop - and the power to create yards after contact:

On Saturday, he played a lot of snaps as a wing offset like a tight end, which is a creative wrinkle. Colorado dictated matchups, forcing a corner to drop into the box (a favorable look to run against), or matching Shenault up against a linebacker in coverage.

Nebraska countered the wing wrinkle with zone looks, which presented different problems because all eyes were on the quarterback.

Zone defenses are particularly susceptible to creative gadget plays, which is what Colorado leaned on to counter Nebraska’s adjustment:

Shenault helped to sell the above play. He feigned to block, then peeled out on a wheel route, elongating his route while gaining outside leverage on the cornerback.

A lot of receivers get antsy in that situation, and they’re eager to shoot upfield. Shenault did a good job of being patient as the slow-developing concept took shape. He worked through his gears effortlessly, creating daylight between himself and the corralling defender. With a better throw, it would have been six points.

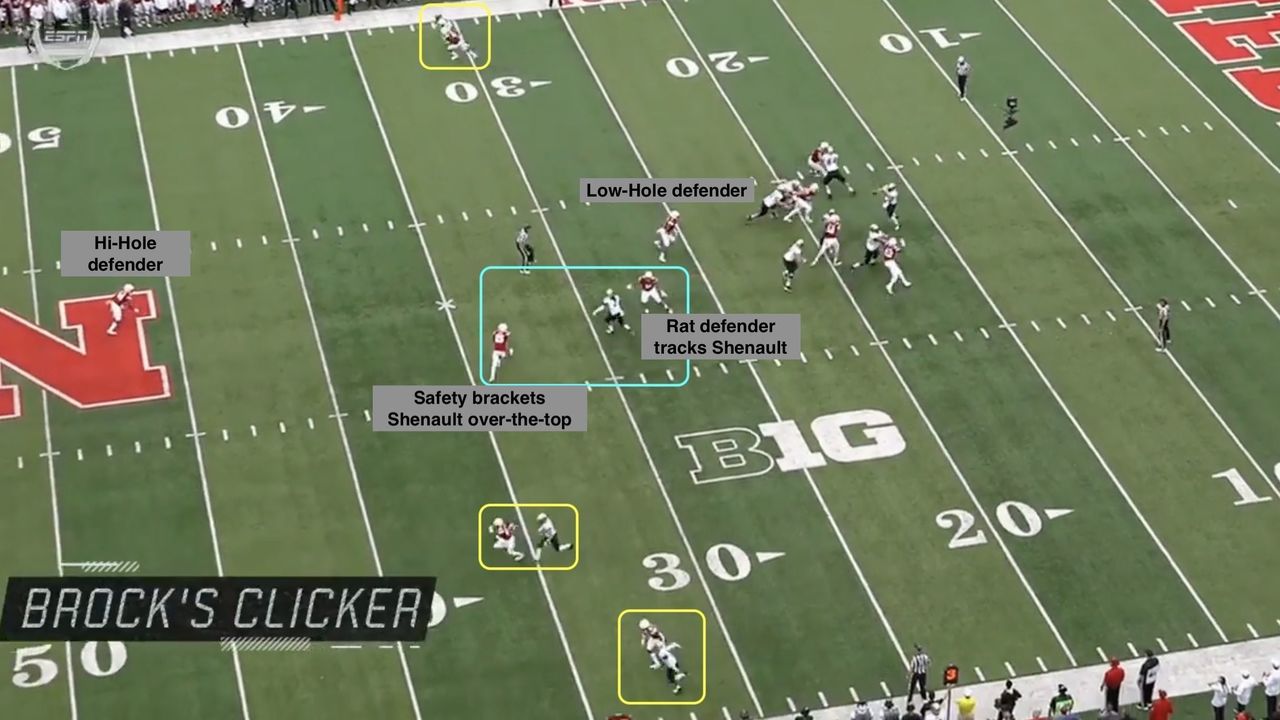

Elsewhere on the field, Nebraska sold out and double-teamed the sophomore. It wasn't a fancy cone coverage, a leverage-based double-team in which a defense doesn’t have to take two of its defenders out of a play regardless of the offensive play call.

Nope. We’re talking about an old-school double-team, with two defenders tracking a single receiver:

On the play above, the Cornhuskers' defense lined up in a six-across look with both linebackers dropping back. One linebacker slipped to the low hole, keeping his eyes on the quarterback. The other ‘backer - the “rat” defender - turned and bolted for Shenault, looking to re-route any in-breaking route.

The rat defender didn’t quite get there. Which was fine, because he had safety help over the top. Nebraska, which started in a two-deep safety set, spun one safety down to bracket Shenault over the top and pick up any crosser. Every other defender played bump-and-run, with a single-deep safety serving as a safety blanket:

That’s an awful lot of attention being paid to one guy. Yet that one guy became open anyway before the safety could pick him up. Unfortunately for Colorado, Nebraska’s front four got home to take down the quarterback before he could hit his favorite target.

Shenault is a special one. Keep an eye on him throughout the season.

Florida’s defense: A tale of gap integrity

Florida’s offense received criticism throughout the Jim McElwain era. But McElwain also sneakily torpedoed the Gators' defense.

Florida’s defensive front looked small, and its front four was routinely run off the ball by schools that had no business competing at the line of scrimmage.

Florida’s linebackers were an equal issue. Their problems were twofold: They struggled with the intricacies of the game, and McElwain prioritizing defenders who could turn, run, and make plays in space made them lighter against the run.

The same issues that plagued the unit a year ago appeared again on Saturday night when Kentucky snapped its 31-game losing streak.

Dan Mullen, Florida's new head coach, fields a defense featuring more flexibility and hybrid gap alignments. Todd Grantham, the Gators' defensive coordinator, likes to use lots of pre-snap movement. But the Gators have been fairly vanilla early in the season. They don’t have the talent to pull off what Mullen or Grantham want to achieve.

Gators defenders are still making routine errors, and gap discipline is non-existent. Two defenders often attack the same gap, leaving a massive void elsewhere.

Starting linebacker Vosean Joseph (No. 11) looked completely lost on Saturday. He consistently filled the wrong gap, pinching a gap further down than his assignment. Kentucky running back Benny Snell took full advantage:

Florida’s front struggles with all the little things, like reading the body position of a teammate and making the right adjustment, maintaining their width against inside runs, and the contain defender setting a hard edge.

Kentucky’s slew of option concepts made matters worse. This is brutal:

That’s on Joseph again. Florida’s edge defender pinched inside, losing his inside shoulder and conceding the edge. Scraping over the top and looping around the outside shoulder of his fellow linebacker would have allowed him to recover.

Defenders don’t do things haphazardly. The edge rusher pinched inside because he spotted it was a gap scheme, pull concept. Otherwise, he would have sat down, or charged into the backfield (as is normal vs. the option). Joseph didn’t adjust the way his teammate did.

Florida switched up its linebacking corps in the second half, with Rayshad Jackson subbing in for Joseph. Jackson, a redshirt sophomore, is a special teams whizz. However, he's made just 14 tackles in his collegiate career, with most of his production coming in garbage time against UAB in 2017.

Jackson isn’t an SEC-caliber linebacker and it showed, with the ugliness continuing, the wrong lanes being filled, and Kentucky’s option attack taking over:

Everyone was fooled on that play. A single-man quarterback counter sits somewhere in every playbook. Yet all of the Gators' second-level defenders cheated toward the play-fake, vacating space for Kentucky’s quarterback to take off and score.

Florida was missing its best off-ball linebacker, David Reese, due to an injury. But Reese is built similarly to the rest of his unit. He's a see-ball-get-ball guy who sorts through the trash and is excellent in space. Florida doesn't have anybody who can come downhill effectively and take on blocks.

That problem is compounded by the down linemen. The team's defensive line is its strength. But it’s another unit built around agility and first-step quickness rather than size. Kentucky ran the Gators' defensive linemen off the ball over and over again on Saturday night:

In his postgame press conference, Mullen talked at length about the need to be more physical.

There isn’t an easy fix on the roster. An ill-equipped strength program has limited Florida for years. Top recruits haven’t developed into SEC-caliber starters, let alone stars.

The likes of CeCe Jefferson - who was suspended for a violation of team rules on Saturday - are more hype than substance. Take the decal and nameplates off, and you see a small, sluggish, ill-disciplined outfit.

Mullen and his staff have a much greater rebuilding job ahead of them than folks understand.

(Photos courtesy: Getty Images)