What does it mean to draft a big man in today's NBA?

Basketball, more than any other sport, naturally selects for size. While a million factors contribute to an individual's ability to play it at the highest level, being large is the game's predominant biological imperative.

But in the NBA there's also a tipping point, past which size can start to become a hindrance. That point has become increasingly clear since the early-2000s rule changes, which legalized zone-style schemes, introduced the defensive three-second rule, cracked down on hand-checking, and laid the groundwork for the pace-and-space era. In a game that's become faster and more perimeter-oriented, big men have been marginalized because they're typically the slowest and least coordinated players on the floor, limited in increasingly important areas like shooting, ball-handling, passing, and defending in space.

There are exceptions, of course. Giannis Antetokounmpo and Anthony Davis are 6-foot-11 and gallop around the court like gazelles; Kevin Durant is listed at 6-foot-10 (and believed to be taller than that) and he handles and shoots better than almost any guard; Nikola Jokic is a 7-footer who might be the second-best passer alive. These players take advantage of their size without being confined by it.

With today's fluid positional archetypes, roles are dictated more by skill sets than physical profiles. Durant and Antetokounmpo, for instance, are taller than some bigs but play more like wings. In that framework, the concept of "traditional big men" has become shorthand for center- or power forward-sized players who play close to the basket at both ends and don't operate as off-the-dribble playmakers, volume 3-point shooters, or perimeter defenders.

At their best, traditional bigs can still be franchise players (Joel Embiid fits both bills), and can still hold immense value as screeners, roll men, rebounders, and rim-protectors. Interior defense is as important as it's ever been. But at the lower end of the spectrum, they also represent perhaps the most widely available player type in the league. Their replaceability speaks as much to the abundance of alternatives as it does to their diminished utility.

Part of the reason the supply of bigs is outpacing the need is that the power forward position is now primarily the domain of wing players. Where teams used to require two bigs to fill out a five-man lineup, traditional bigs are now centers and centers alone. (Two-big alignments only accounted for about 9% of all NBA minutes last season, down from nearly 60% in 2011-12.)

Remembrance of busts past

It's fascinating to look at these trends through the lens of the draft.

The draft represents possibility, particularly for lottery teams that pick at the top. Those cellar-dwellers are usually looking for franchise saviors, which makes the top of the draft something of a window into how rebuilding teams view the future of the league. And for a time, a lot of them badly misread that future. The NBA seemed to change at a faster pace than did the conventional wisdom about selecting its next batch of players.

Even as gameplay trends bent more and more toward shot-creators, the age-old truism that "you can't teach height" continued to govern certain draft decisions. Andrew Bogut (Milwaukee, 2005) was picked first overall in a draft that featured Chris Paul. Greg Oden (Portland, 2007) went No. 1 over Durant. Hasheem Thabeet (Memphis, 2009) went No. 2 ahead of James Harden and Steph Curry.

Drafting big is considered drafting safe - whatever shortcomings a 7-footer may come into the league with, he'll come with the unalienable skill of being huge in a game featuring goals set 10 feet off the floor. But the majority of memorable busts throughout history have been big men, from LaRue Martin to Sam Bowie to Michael Olowokandi to Kwame Brown to Darko Milicic to Nikoloz Tskitishvili to Andrea Bargnani to Oden to Thabeet to Jahlil Okafor.

It's obviously easy to question those decisions in hindsight, and plenty of wings and guards go bust, too. But draft history is littered with examples of how fixating on size can lead teams to overlook other flaws and red flags in prospects' games. It may be unfair to harp on the Oden pick given the cosmically unlucky barrage of injuries that wrecked his promising career, but there's also some evidence that taller players get hurt at higher rates than smaller ones, which eats into the "safe pick" argument somewhat.

Though draft trends eventually evolved with the times, plenty of recent decisions have seemed to reflect outdated thinking. Just two years ago, Deandre Ayton (Phoenix) and Marvin Bagley (Sacramento) were taken first and second overall - ahead of Luka Doncic (Dallas via Atlanta).

What's telling about the Oden pick is that it wasn't the least bit controversial back in 2007. In 13 years since, the league's been taken over by wing creators like Durant and dynamic pick-and-roll playmakers like Doncic, while continuing to devalue centers, which is why the Ayton pick brought far more scrutiny.

Both selections were made under the pretext of safety. But opportunity cost is a risk in its own right.

Evolving draft trends

In fairness to the Suns, Ayton isn't just some galoot they drafted solely for his 7-foot, 260-pound frame; he's a skilled player with a realistic path to offensive stardom. But big men need to do a lot to become pillars of contending teams in this era. For all the unicorns dotting the NBA landscape, when was the last time a team won a championship with a center as its best player?

Defensively, they either need to be able to routinely switch out onto the perimeter and track smaller players in space, or be monster back-line anchors around the rim. On offense, they need to have some combination of a dominant low-post game, face-up chops, a credible 3-point stroke, elite high-post passing, and finishing ability on the roll.

The bigs in the league who can be called franchise players - Davis, Jokic, Embiid, Bam Adebayo, Karl-Anthony Towns, and Rudy Gobert - either possess a majority of those skills at both ends or are so overwhelmingly good on one side of the ball that their shortcomings on the other can be overlooked. And even then, the respective struggles of one-way bigs like Towns (on defense) and Gobert (on offense) have put firm ceilings on their teams.

So, deciding whether to select a big man at or near the top of the draft has become a matter of sussing out the type of big they can be at the NBA level. And teams have been getting more discerning in that regard.

There's still a premium on size - tall ball-handlers might be the league's most sought-after commodity - but more as an ancillary benefit to a player's skill package than simply for size's sake. Last year, the only traditional big man taken in the lottery was Jaxson Hayes, who went eighth overall.

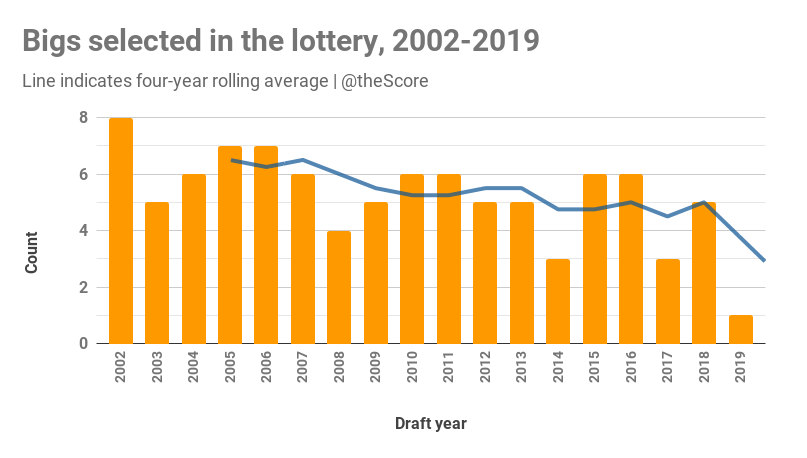

Here's a look at the number of bigs* who've been selected in the lottery each year since 2002, which was the first draft after the illegal defense rules were lifted (the hand-checking rules were implemented in 2004):

According to research from Dimitrije Curcic at RunRepeat, the height of the average NBA rookie peaked around 2000 at just under 6-foot-8, and by 2019 had dipped down to about 6-foot-6.

That trend looks set to continue with this year's draft, in which the only bigs considered locks to get picked in the lottery are James Wiseman and Onyeka Okongwu (depending on how you'd classify 6-foot-8 tweener Obi Toppin).

Looking ahead

Reports indicate Wiseman is almost certain to hear his name called among the top three picks Wednesday, and several mocks project Okongwu to go top five. Both have considerable potential, but neither represents the kind of paradigm-shifting evolutionary advancement that made bigs like Davis and Towns slam-dunk top picks in the modern era.

Wiseman is considered the draft's safest pick, and in this case it's hard to disagree. He's listed at 7-foot-1 with a 7-foot-6 wingspan and 9-foot-4 standing reach, and he pairs those extraordinary measurables with nimble feet and elite leaping ability. While his body of work is small (he played only 69 minutes of college ball for reasons we don't need to rehash here), his literal body is big enough and dexterous enough to make him feel virtually bust-proof. Even a lower-end outcome could see him settle in as a lob-feasting rim-runner with major gravitational pull as a roll man.

For now, he decidedly lacks the softer skills the aforementioned franchise bigs possess; he doesn't create shots for himself or for others and doesn't read the floor particularly well. That can all change in time, of course, but scouting reports and film from his brief college cameo paint Wiseman as more DeAndre Jordan than Embiid. Absent a refined post game, 3-point range, or passing chops, he might need to grow into a Gobert-level rim-protector to be a legit franchise player.

To be clear, a DeAndre Jordan career arc would not be a remotely bad outcome. Jordan's made three All-NBA teams and a pair of All-Defensive teams, and would undoubtedly be a top-10 pick in a 2008 redraft. But as a non-shooting, non-playmaking big, he represents the high-end version of a relatively common archetype.

On one hand, you can argue that unpolished but physically gifted rim-runners like Jordan (35th), Clint Capela (25th), and Mitchell Robinson (41st) are actually undervalued and have been drafted too low. On the other hand, you can make a case that it's easy to find those types of players later in the draft. Either way, the solidity of Wiseman's floor isn't being disputed. The pressing question is whether he has a ceiling worthy of a top-three pick.

"Simply put, few executives doubt that his size, length, and athleticism will translate into being a starting-quality NBA center," The Athletic's Sam Vecenie wrote in his mock draft, which has Wiseman going second overall to Golden State. "Where the disagreement comes is with whether or not he has star upside, something that is necessary for a team to be willing to take a center at the top of the draft in today's day and age. Some think his defensive ability on the interior does bring that kind of upside. Others are less convinced."

Okongwu, at 6-foot-9 with a 7-foot-1 wingspan, doesn't have quite the same physical tools to fall back on, and his ability to score at the NBA level is a question mark. But he's a similarly impressive athlete who appears more likely to break out of the traditional mold and avoid getting pigeonholed at center.

He can do a bit more with the ball, and seems to possess the combination of length, strength, and lateral mobility to be a multi-purpose defender. For what it's worth, Okongwu has drawn comparisons to - and purports to model his game after - Adebayo, the closest thing there is to a modern big-man prototype outside of Davis.

It might be more illuminating to see what the decision-making calculus on Wiseman and Okongwu looked like in a different draft year because a major reason they're uncontroversial top-five picks in 2020 is the lack of better options in an ostensibly weak class.

The Warriors' position at No. 2 also changes the equation, especially because Wiseman would fill a clear need on their roster. If they make the pick for themselves, landing a future star won't be as much of an imperative as it is for most teams that pick second overall. If ever there was a team that could afford to draft for floor and short-term fit rather than long-term upside, it's the one that already employs Curry, Klay Thompson, and Draymond Green.

By the same token, the lack of any clear-cut, no-brainer top picks is what makes this an interesting intellectual exercise. Wiseman and Okongwu could very well turn out to be the best players in the draft. In a copycat league, it's also easy to imagine a scenario in which teams overcorrect toward perimeter players. Picking a guard or wing simply because that's the direction the league is trending would be just as foolish as all those past decisions to draft bigs primarily because size is an unteachable skill.

The objective is always to get the best player available, regardless of size or position. Sometimes, the safest picks are also the best picks.

Joe Wolfond is a features writer for theScore.