Jacob deGrom's a late bloomer. Will that affect his Hall of Fame chances?

When Cleveland's Trevor Stephan, a Rule 5 pick, took the mound at Comerica Park on April 3, he became the 10,000th person to pitch in a major-league game, according to the Baseball-Reference.com database. The total number of players in major-league history stands at 19,963. If it were possible to gather everyone who played in a major-league game and seat them in, say, Fenway Park, the stadium would remain far from capacity. And if it were possible to gather the entire collection of Hall of Fame starting pitchers and seat them in a couple of the field boxes behind home plate, they would only fill four and a half rows.

Framed that way, you get a better sense of how few people have actually played in the majors, and how select it is to be in the company of other Hall of Famers. Out of the now 10,036 major leaguers to pitch in a game, out of countless millions who hoped to do so as amateurs, only 68 are enshrined primarily for their work as a starting pitcher.

So it's worth asking: How much more does Jacob deGrom have to do to eventually become one of them?

Has he done enough already? If his career is relatively short but brilliant, can he alter how voters consider Hall performance?

The New York Mets' uber ace continues to dazzle the baseball world. He's the game's best starting pitcher since 2017 by WAR and ERA, and remarkably continues to improve in his early 30s. He's so good there is some talk about whether deGrom will have enough longevity, enough time on the field, to earn Hall of Fame enshrinement given the obstacle of the late start to his career. Tom Tango, MLB's senior data architect, ran a Twitter poll over the weekend, and the vast majority of respondents believed deGrom owns a 75% chance or better to make the Hall. How much more must he do to increase his chances?

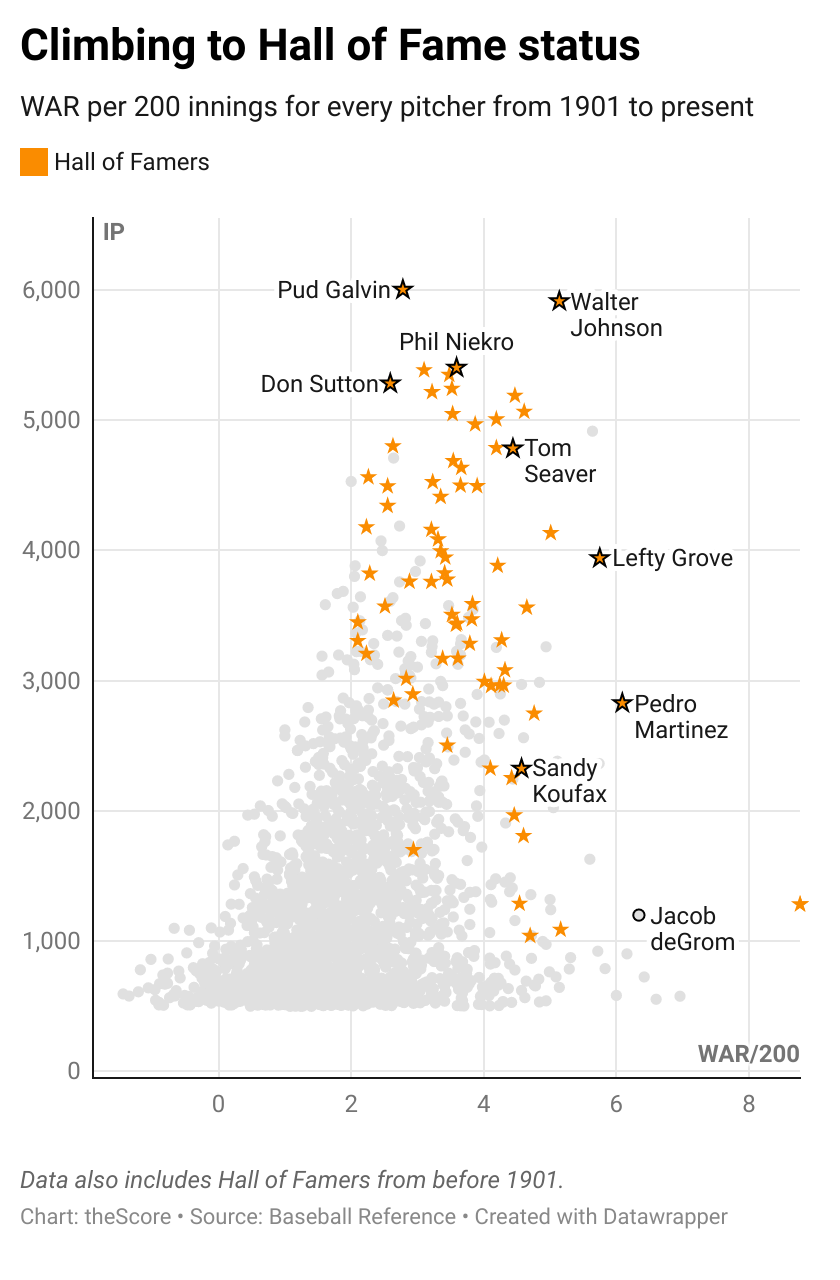

Given his unreal performance and unusual career shape, there's no one like deGrom. It's tough to place him in context.

In a couple months, deGrom will join Clayton Kershaw as a 33-year-old. DeGrom was a freshman shortstop at Stetson (Fla.) University when Kershaw broke into the major leagues in 2008. DeGrom didn't convert to pitching until he was a junior. By the time Kershaw won his first Cy Young in 2011, deGrom had made six starts in rookie ball and was recovering from Tommy John surgery.

And just as he's changed what many thought possible about performance on a pitching mound - he's struck out 50 of the 101 batters he's faced this year and allowed only a single run - perhaps deGrom will also change what many think is necessary on a Hall of Fame resume. A Hall debate is often about the quality of a peak versus the accumulation of stats. Ideally, a candidate does both. But as innings are reduced across the board for starting pitchers, perhaps Cooperstown cases will become much more weighted toward peaks.

By traditional standards, deGrom would face an impossible task. He'd have to win 228 more games to reach 300, which was traditionally a clincher for enshrinement. Yes, as dominant as deGrom's been, he has only 72 wins in 187 career starts despite a lifetime 2.55 ERA. Oh, those Mets teammates of his.

He's also well short of late Roy Halladay's 203 wins, the fewest of any starting pitcher to be inducted since Rube Marquard in 1971 (201 wins).

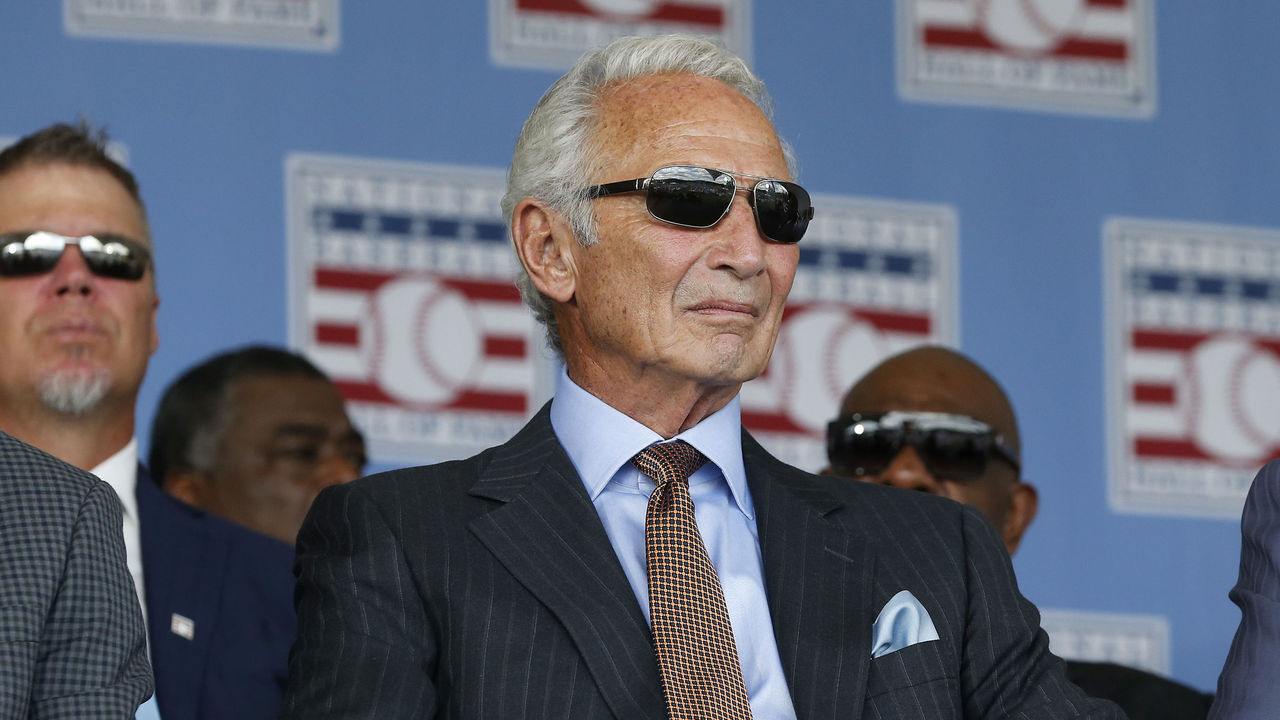

Perhaps the best historical comp for deGrom is Sandy Koufax, who finished with only 165 wins, well short of the average for a Hall of Fame starter (274.9 wins) at the time of his induction in 1972.

Koufax pitched 12 years, amassing four top-three finishes in Cy Young voting, all consecutive, winning three times from 1963-66. He retired at the peak of his powers following the 1966 season due to injuries. DeGrom owns two Cy Youngs and finished in the top eight in Cy Young voting four times since 2017. Koufax got into the Hall based largely on his brilliant four-year run. DeGrom enjoys a better career ERA+ (153) than Koufax (131), and deGrom's ERA+ since the start of 2017 (165) is near that of Koufax's 1963-66 run (172).

If deGrom wins another Cy Young this year, is his resume much different from that of Koufax?

There are some other outliers in terms of accumulation. Dizzy Dean (150 wins) and Addie Joss (160), who died of tuberculous meningitis in 1911 at age 31, are two others who didn't reach 200 wins.

DeGrom, like almost all modern pitchers, faces an innings problem when it comes to reaching historical benchmarks. Of those 68 starting pitchers in the Hall of Fame, 56 reached 3,000 innings. No active players have pitched 3,000 innings and only two have exceeded 2,600: Justin Verlander and Zack Greinke. DeGrom stands four outs away from 1,200.

BBWAA voters are slowly evolving in their practices and considerations. More voters are valuing new-age measures like wins above replacement, though not uniformly. By advanced measures, deGrom (38 WAR) doesn't have to go far to surpass Jack Morris' 43 career WAR. Some voters are devaluing wins. They're well aware of the lack of support deGrom's teammates often give him and they know that careers and outings are shortening.

And if one weighs peak performance heavily over longevity, there's an argument to be made that deGrom's already a Hall of Famer.

Consider that on a WAR-per-inning basis, the only pitcher to throw at least 1,000 innings and rank better than deGrom is Mariano Rivera, who, of course, was a reliever.

Moreover, deGrom's career ERA+, which adjusts for ballpark and run environments, trails only that of Rivera, Kershaw, and Pedro Martinez among all pitchers to have tossed at least 1,000 innings.

If deGrom records another top-five finish in WAR this year, he'll join Bob Gibson and Greg Maddux in an eighth-place tie with three such all-time finishes.

In looking at the best seven years of a pitching career, deGrom does rank quite well, sitting 108th.

On a pure skills basis, few have been more talented. He also keeps getting better. Consider that his swinging strike rate was a record for a starting pitcher last season at 20% and it's climbed to 24% this season. He owns the top two and four of the top 10 fastball velocity seasons for starting pitchers at ages when those speeds are usually in decline. No one owns deGrom's blend of command, pitch diversity, or velocity.

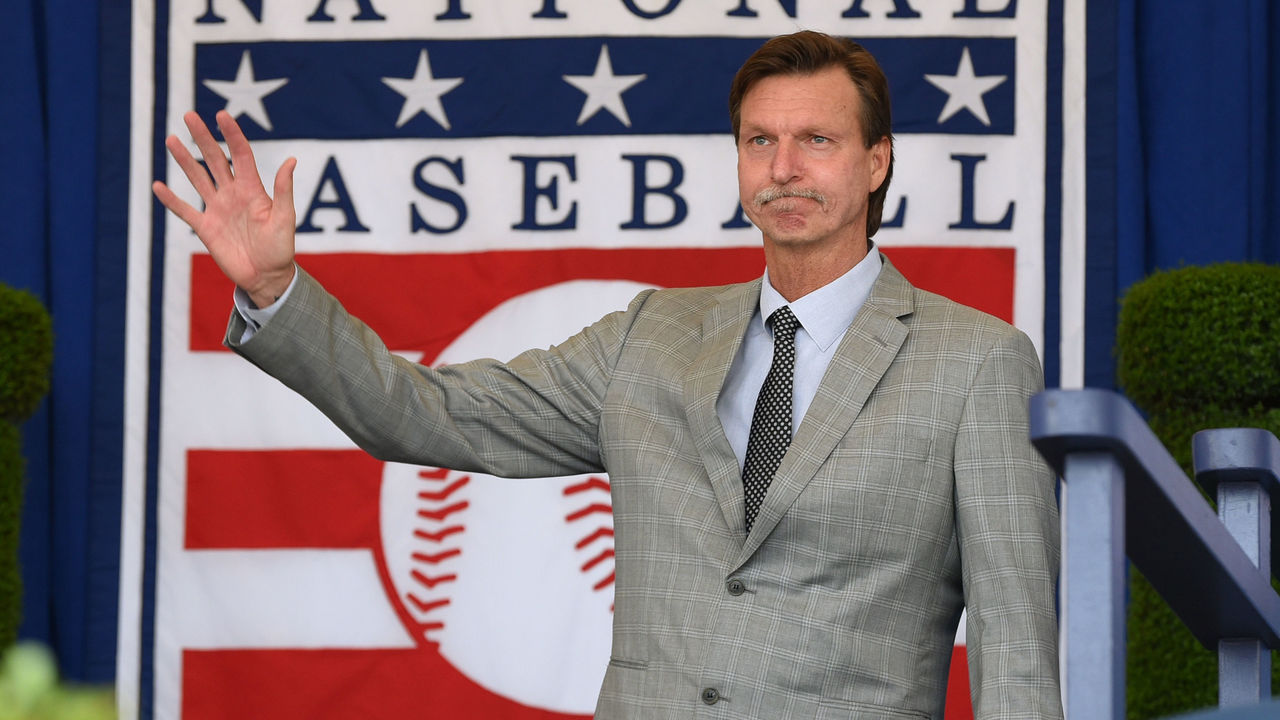

Perhaps deGrom will make this debate moot and have a Randy Johnson-like career in his mid-to-late 30s. After age 32, Johnson recorded 199 wins to become the last modern-era player to reach 300 wins.

Another way to consider who ought to be in the Hall is to consider performance compared to that player's contemporaries, rather than historical benchmarks. For instance, there are only 17 active pitchers with 100 or more wins and only two have reached 200 (Verlander has 226, Greinke 210).

As MLB.com's Mike Petriello found, only 3.5% of all pitchers who recorded 500 or more innings have reached the Hall. DeGrom is near the top 3.5% of his contemporaries. Among 21st century pitchers, deGrom ranks within the top 5% in WAR among pitchers to throw at least 500 innings.

The problem is that recent generations of pitchers are underrepresented in Cooperstown.

For instance, Petriello found 4.8% of pitchers born between 1931-40 reached the Hall. In 1941-50 it was 3.7%, falling to 2.5% in 1951-60. It leveled out a bit in 1961-70 (2.7%) before crashing to 0.8% for 1971-1980 birth years.

Halladay and Martinez are the only two starting pitchers in the Hall who were born within the last 50 years. Players born later? Good luck, especially if ballots remain crowded and constrained by a maximum of 10 affirmative votes per ballot.

Who knows what the voting electorate will look like five years after deGrom stops pitching. Who knows how Hall standards might have changed. Who knows what numbers deGrom might have accumulated. But whether it's deGrom or another pitcher with a short but brilliant career, the question of what it means to be a Hall of Famer is going to be tested.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer. Follow him on Twitter at @Travis_Sawchik.