Week 1 Film Study: Alabama still unstoppable, Miami O-line a disaster

You'll be told not to overreact to Week 1. Poppycock! Overreact at will.

Let's review the film and break down some interesting tidbits from an entertaining weekend on the field:

Alabama's offense is schematically unstoppable

The most intimidating thing in college football used to be Nick Saban's defense. Now, it's his offense. Like all modern pace-and-space styles, Saban wants to play one-on-one football. And more often than not, his side is better than yours.

Louisville found that out the hard way.

Saban has continued to evolve and adapt his system, and change was evident on Saturday. The new raft of offensive coaches has shifted the team's scheme from a focus on spread play-action concepts to run-pass options (RPOs) - the "you go here, I go here" kind.

In theory, RPOs mean a defender can never be right. In Week 1, the Crimson Tide supplemented their classic outside/inside-zone ground attack with some hold-fold reads:

On the play, quarterback Tua Tagovailoa reads a defender to his right:

If the defender holds his position, Tagovailoa would hand the ball to his running back. But if the defender crashes toward the line of scrimmage - as in the example above - the quarterback pulls the ball back and flips a pass into the vacated space. Football doesn’t get any easier.

Teams that are defending RPOs - particularly against Alabama - want to play out of split-safety looks, typically running some variation of a quarters-match defense (four deep defenders running matchup zones). That allows them to compress the field, double a slot receiver, and limit explosive plays.

Keep two defenders deep, however, and you lighten the box. That's a non-starter against Alabama, particularly since Saban embraced spread-option football, adding a quarterback-run element to the system.

The Tide's offensive line and backfield is littered with blue-chip, future-pro talents. Tacking on a mobile quarterback forces the defense to cover an extra gap, which is a defensive coordinator's worst nightmare. It's tough enough to stop Alabama from rampaging downhill when the numbers are in your favor, let alone when you gift away the numerical advantage.

It was all too much for an overmatched Louisville defense to deal with. Take this play for instance:

It's a quarterback lead zone, run out of a "nub" play design - a receiving formation on one side (the right, in this case), and a running formation to the other. On the play, the Tide's tight end climbs up to seal the first second-level defender in sight. Meanwhile, the running back leads the way for his quarterback, clearing out the outermost defender. Through its formation alone, Alabama was able to dictate one-on-one matchups. Tagovailoa ran untouched to the end zone.

An overwhelming run game, supplemented by that constant threat of a quarterback run, forces an opponent to start spinning its safeties, rotating them toward the line of scrimmage in order to form a wall at the second level and get an additional body in the box.

That's when Tagovailoa feasts. Adding a guy to the box removes him from coverage. Now the math problem flips, as it creates one-on-one matchups in the passing game rather than on the ground. And guess what? Tagovailoa and his receivers are blue-chippers, too, and they can take advantage of favorable matchups - something Jalen Hurts isn't always able to do.

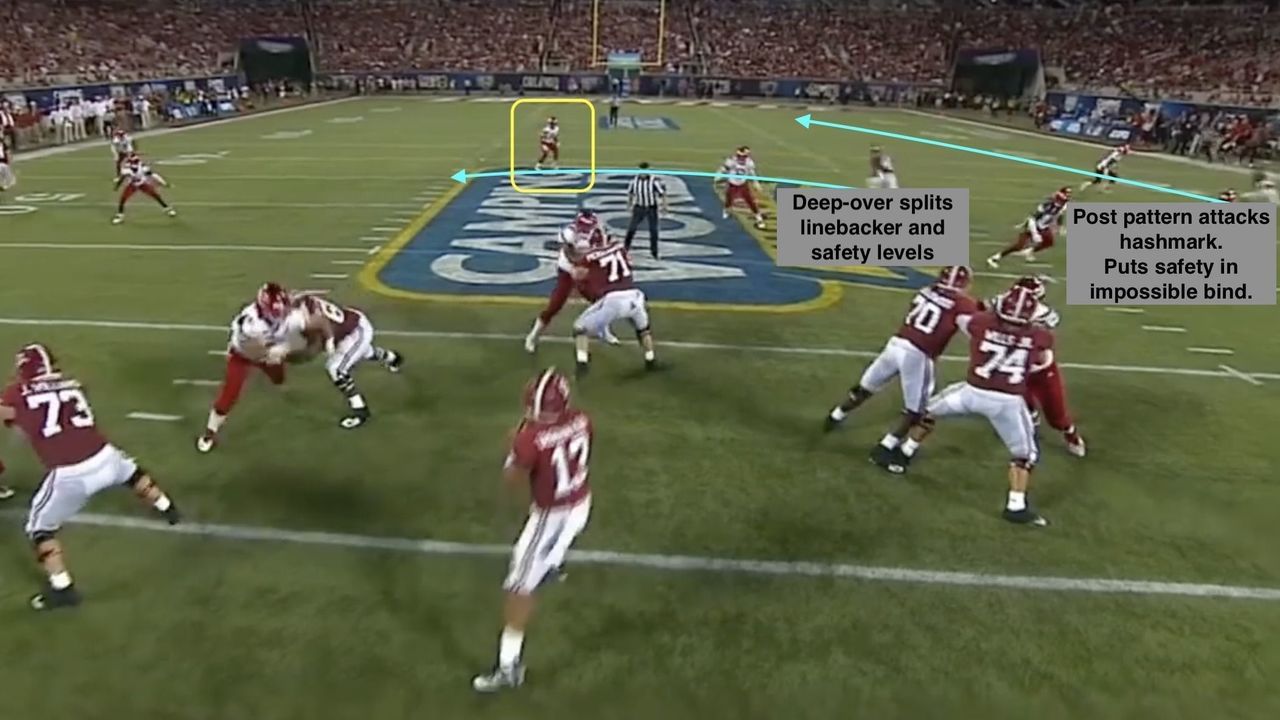

Louisville began to spin its safeties early in Saturday's contest, leaving a safety on a single-high island. Alabama isolated him and attacked the weakest point - the seams:

It doesn’t get much better than that. Alabama ran a deep-over route tagged with a post, which is a classic high-low concept. The safety was put in a no-win situation - either driving in on the crossing route or shuffling over to help cover the post:

In this case, he opted for the crosser and Tagovailoa nailed the post.

Schematically speaking, the only way to slow down this 'Bama offense is to consistently generate organic pressure with the front four while deploying a pair of wicked smart safeties in the secondary. Theoretically, a team could then use a two-deep package and bracket in-breaking routes while generating enough pressure up front to throw off the passing game and slow down the rushing attack.

But those creatures don't grow on trees. And even then, it probably wouldn't be enough. The rest of Saban's squad is still better.

Alabama was previously a team loaded with talent, but flawed at the most important position on the field. The offense caused the same math problem a year ago, but Hurts didn’t always make opponents pay. Now, Saban has one of the most gifted quarterbacks in the country.

At this point, it's flat-out unfair.

Miami has major protection issues

Miami lost the battle for the line of scrimmage on both sides of the ball against LSU on Sunday night. For a team with genuine conference title hopes, it was downright embarrassing.

A bunch of the blame will be placed on quarterback Malik Rosier. That's not entirely wrong; he's not good enough. But his offensive line did him no favors.

LSU defensive coordinator Dave Aranda, the highest-paid coordinator in the land, bamboozled Miami with his series of man blitzes and zone-pressure packages. Aranda is a blitzing savant. Anybody could rush, and anybody could drop. It's tricky to pick up. Miami had no idea who was coming or going.

The O-line looked lost. The play below is indefensible:

How do you end up in a situation where "Buck" linebacker K'Lavon Chaisson, an explosive, powerful, intimidating pass-rusher, is allowed to run free into the chest of your quarterback?

The left side of Miami's line isn’t springy enough to compete at the highest level. Those guys struggle against serious SEC-caliber speed. They can't get out of their stance in time or dip against speedsters who swoop around the edge.

Athletic flaws are tough to cover up, but you can compensate - particularly against slower-developing pressure concepts - by being switched on mentally and being in the right place to block the right guy.

On the play above, Miami's left tackle was so concerned with picking up the boundary corner blitz that he ignored the guy standing across from him. Meanwhile, the left guard fell for the initial movement of LSU's interior defensive lineman, shooting toward the left tackle before cutting toward the center. Rosier paid the price.

This wasn't a one-off. Even when Miami kept extra guys in to help block, LSU still ran free to the quarterback:

The play above is as basic as it gets. It's a one-for-one zone blitz by LSU, in which a first-level guy drops and a second-level defender rushes the passer. Specifically, LSU's edge defender drops into the low-hole spot, displacing the the "Mike" linebacker, who runs in a straight line to the quarterback. And that's despite Miami having six blockers against four rushers. Terrible.

All night, Miami suffered breakdowns in protection:

There wasn't one specific flaw, or one player whom Aranda and company picked on. Miami's entire group struggled.

The Hurricanes' staff entered the year believing the quarterback spot was the only issue, and that they could coach around it and return to the ACC championship game. The offensive line could prove to be a greater concern.

West Virginia's defense is surprisingly frisky

All eyes in Charlotte were on Will Grier, and he was great, but Dana Holgorsen's defense stole the show. The unit proved to be positively energetic, which is a great sign for a team hoping to compete with Oklahoma at the top of the Big 12.

The Mountaineers consistently fooled Tennessee’s offensive line. They ran a serious of stuns, twists, and gap exchanges, muddying any read concepts and forcing linemen to communicate and display awareness, rather than relying on their athletic traits.

The smartest tactical switch was stemming the defensive line. That means lining up defensive linemen in certain gaps, and then moving them prior to the snap. Tennessee would line up for a play and identify which offensive lineman was blocking which defender. After the protection was set, West Virginia moved, so the Vols had to re-identify who was blocking whom.

Tennessee couldn't cope. West Virginia's down linemen lived in the Vols' backfield.

Kenny Bigelow was the brightest star. The former USC man was once a blue-chip, top-five recruit in the country. A couple of knee injuries later, he was viewed as dispensable by the Trojans.

When he showed up in West Virginia, the team feared it had received damaged goods. Why would USC let him go? He couldn’t be as athletic as he once was, right?

Wrong. Bigelow looked every part the speed-to-power menace he was billed as coming out of high school. His speed off the snap is frightening. He combines that with an assortment of pass-rush moves.

Bigelow bullied Brandon Kennedy, Tennessee's center, who isn’t in the same athletic league. By stemming its defensive line, WVU could assure a one-on-one matchup. It wasn't a fair contest:

Bigelow’s emergence could be a game-changer. Holgorsen knew his offense would be good, but he was unsure about the defense. Performances like the one on Saturday are more than a little encouraging.

Notre Dame beat Michigan at its own game

Jim Harbaugh and Shea Patterson stole the headlines following Michigan’s defeat at the hands of Notre Dame. That's fair, as their first outing as a coach-quarterback tandem was a borderline disaster. But let's give some credit to Notre Dame's new defensive coordinator, Clark Lea.

Sure, Lea got a little lucky. He faced a quarterback being squeezed into an ill-fitting system. Michigan's pair of young offensive tackles literally gifted a quarterback pressure on every other drop-back, per ProFootballFocus.

But Lea still beat Michigan at its own game. Wolverines defensive coordinator Don Brown, is famous for his quirky packages. He's constantly seeking to get as much speed on the field as possible, and runs as many trap coverages as any defensive coach this side of Bill Belichick.

Lea's defense looked almost like a mirror image. Notre Dame ran a series of five-across, six-across, and double A-Gap "mug" fronts, dropping linebackers down to the line of scrimmage before either blitzing, dropping into coverage, or green-dogging. If your man stays into protect, blitz!

Notre Dame wasn't content with just lining up guys and letting them stay or go, though. Lea ran a barrage of zone blitzes and crisscross looks, with linebackers intersecting and switching their gaps post-snap. There was a high-five party in the backfield, and everybody was invited.

Patterson had to figure out who was coming and who was going. That takes a couple of extra beats, and his linemen couldn't hold up. The quarterback looked flustered and antsy to get rid of the ball - even when both linebackers bailed and he had more time.

Notre Dame did a great job of dictating the terms of engagement and keeping Michigan off-balance. That’s another Brown staple. Harbaugh and Co. got a taste of their own medicine, and I don’t think they enjoyed it.

(Photos courtesy: ESPN)