Heisman Film Room: Tua Tagovailoa is a star in the making

We're used to Alabama's running backs winning or competing for the Heisman. It often appears the voters hand the thing out as a kind of team award - "You guys were dominant, so here's a trophy for the figurehead on offense."

This year will be different. Finally, Nick Saban has a quarterback with genuine Heisman aspirations (feel free to groan).

Tua Tagovailoa enters as a heavy favorite to make it to New York after his performance in the national title game made him a household name.

The only thing holding him back: a quarterback competition. The new redshirt rule and Jalen Hurts' 24-2 career record give the veteran quarterback an outside shot of reclaiming his spot from the young pup.

Alabama shouldn't give it to him.

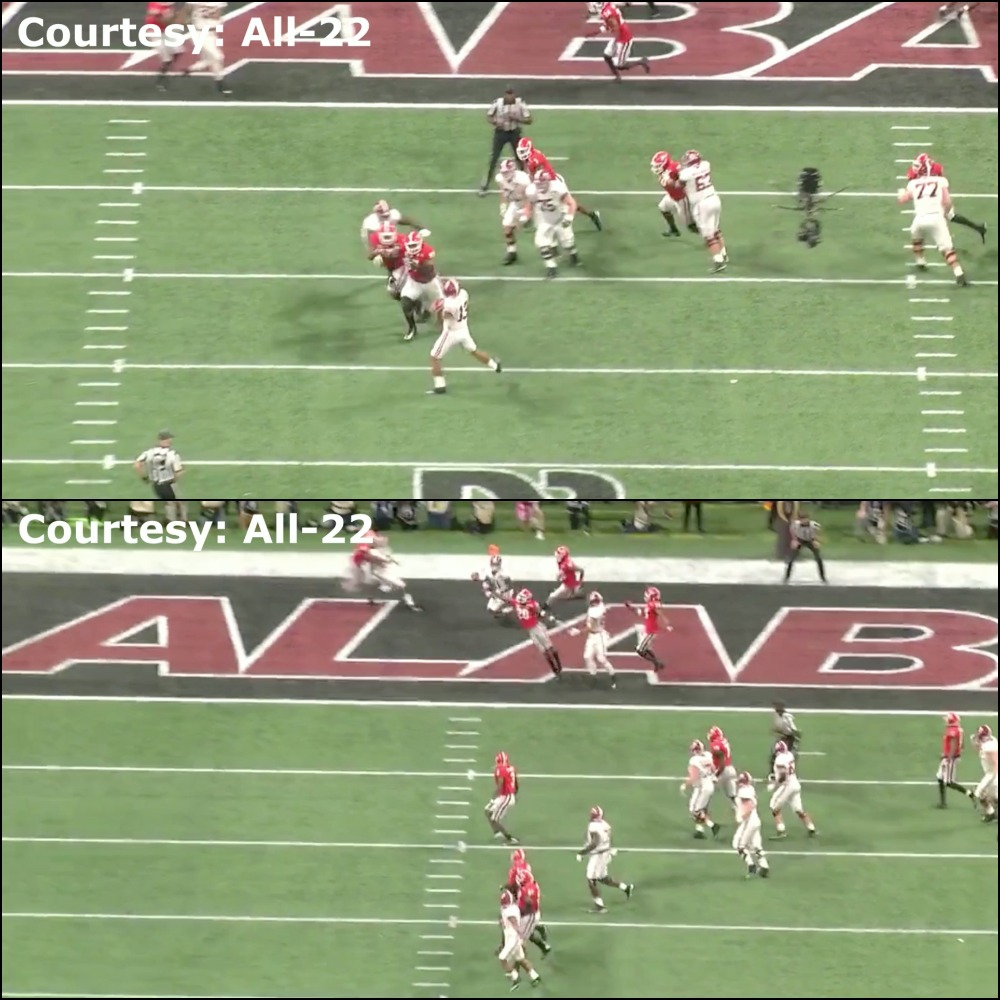

Tagovailoa stepped in against a snarling, fire-breathing Georgia defense on the grandest college stage of all and more than held his own. Freshmen don't marshal come-from-behind victories while coming off the bench against a top-10 defense with NFL-caliber speed. What he did was bonkers, really.

(Photo courtesy: Getty Images)

Small sample size or not, Tagovailoa showed against the Bulldogs - and in mop-up duty throughout the season - that he has something special; something that elevates him above Hurts.

He's a perfect fit for the modern version of Saban's attack, which blends spread-option principles on the ground with Air Raid passing concepts. As he showed in that electric championship performance, Tagovailoa can stretch the field vertically in a way Hurts failed to in his two years as the team's starter. Oh, and Tagovailoa happens to be a better improviser, too.

Still, there are some issues that will give Saban and his staff pause. Tagovailoa isn't perfect. As a thrower, he's imprecise, often indecisive, and arrhythmic.

He's a feel player. He likes to improvise. Like most young quarterbacks, he plays see-it-throw-it football, rather than the rhythm-based passing style coaches crave (tying the quarterback's drop-back to his receiver's steps).

Alabama did a nice job of restricting what he was asked to read during his freshman year, not overwhelming the young QB. Tagovailoa sports rare field vision and awareness, and some full-field reads were built into the system. For the most part, however, he was given a heavy dose of half-field reads (reading only one side of the field), saving him from himself.

Take this deep cross with a double-post concept, for instance:

That's something the 2017 staff picked up from Lane Kiffin's time in Alabama: a deep drop from the shotgun off play-action. Former OC Brian Daboll did a nice job of using small wrinkles to buy his quarterbacks time to make decisions.

It's an atypical style. It gives the quarterback plenty of time and room to scan the field. The play concept restricts the read for the quarterback. It's classic high-low stuff. Tagovailoa plants his eyes on a patch of grass or singular defender. Once he sees one of his guys come into the picture, he rips the throw. There's no need to worry about any of the complexities of rhythm-based attacks.

Those tweaks are important, as Tagovailoa is a serial gambler. He wants to get the ball out of his hand and vertical in a hurry. That's a nice switch-up from Hurts, who routinely refused to throw the ball beyond the sticks. But it routinely leads to indecisiveness, with throws left on the field or forced into dangerous spots.

Everything needs to be snappier: his decisions, his processing, his release. Not every play has to be a home-run shot. Sometimes, you just have to hit the back foot, get the ball out, and move on with the game. Keep the offense on schedule, as coaches say. Tagovailoa is so keen to hit the deep pass he'll hold onto the ball too long.

Other times, he panics. You can almost feel his indecision through the TV screen. Before you know it, he's chucked a ball into a sea of bodies.

Yuck.

Flashes of that special field awareness are there. His most famous throw, the overtime dagger to win the national championship, is a great example:

Sure, it came on a blown coverage - the near-side cornerback screwed up what should've been a four-deep or quarters look. But watch how quickly Tagovailoa snaps his neck toward that side of the field and delivers the ball before the boundary safety can corral from the hash.

He has to get better at anticipating his throws against particular coverages. You can't learn that stuff standing on the sideline.

It's also fair to knock his precision. He completes passes, but they're not always precise. There's a difference. Completion percentage is about the play design versus coverage, the protection, how receivers ran their routes, and the accuracy of the quarterback's throw. It's often credited to a quarterback, but really it's a team stat.

Precision, meanwhile, is all on the QB: Where does he put the ball? Does he throw differently against different leverages? Does his receiver have a chance to run after the catch? Does the receiver need to break stride?

Watch how Tagovailoa leaves this throw behind his receiver, forcing him to turn back for the ball:

Still, the good easily outweighs the bad.

Hyperbole ensued following Tagovailoa's national championship performance. That inevitably led to a backlash. Don't overact, the critics said. It was one half. Look at the flaws.

The truth, as always, is in the middle. Remember: we're judging on a meager 58 drop-backs. That makes the evaluation tougher. But it also means he hasn't had a bunch of time to work on things and correct mistakes.

Tagovailoa wasn't great throughout 2017, but the potential he flashed in high school translated to the college game. No stage was too big. Defenses weren't too fast. He has the skills to be really, really special.

Some young guys grow in increments. Tagovailoa honing one skill now doesn't mean he'll neglect the others forever.

His release can be funky at times. He'll drag his arm down toward the turf before raising the thing up like he's chucking a javelin. Fixing that will take reps. When needed, though, he adapts. It's as though survival skills kick in.

Tagovailoa is a quality off-platform thrower, meaning he can throw from unorthodox angles despite his feet not being set. In those instances, he plays on instincts. He shortens his release. He whips his arm. He can sling any throw from any release point he likes. It's more natural.

That's a great throw under fire. It would be easy for a player with his foot speed to bail out of the pocket, as Hurts often did. Tagovailoa appears unafraid to take a shot as long as he can get the ball where it needs to be.

Don't confuse that with a lack of pocket mobility, though. He may not scamper away, but Tagovailoa shows enormous potential at manipulating the pocket, maneuvering around to find the right throwing lane, hitting stick-slide-climb throws, and dancing around to buy time for his receivers.

The numbers concur: Tagovailoa was sacked on 3.8 percent of his drop-backs. By comparison, Hurts - who would look to run away from danger rather than deliver a throw - was dropped by defenders on 8.6 percent of his drop-backs.

Freshmen aren't supposed to move so calmly; they're supposed to panic. Pair that with natural arm talent and you have a deadly weapon from inside the pocket.

All of this lends to his creativity. Yes, it leads to him holding the ball too long on quick drops, but it also leads to moments of magic in which he keeps plays alive with his feet and delivers the ball to spots where only his receiver can make a play.

Above, on fourth down, Alabama motioned to empty. That gave Tagovailoa two signals: it's man coverage, and if there's a blitz, someone will be open. Georgia mushed its rush, looking to contain the quarterback in the pocket and dropping seven defenders into coverage.

Tagovailoa recognized it, holding onto the ball a tick longer than he would have preferred. He passed up an open man in the flat. Nobody else was open. With two defenders bearing down on him, he delivered a strike, moving to his left, with his body weight moving backward. Talk about off-platform.

Somehow, he contorted his body to get enough zip on the ball and squeeze it by the closing Georgia defender:

The degree of difficulty on that throw was just shy of impossible.

It'll be fun to see how new 'Bama OC Mike Locksley uses Tagovailoa in the run game. It could be the key to his Heisman chances. You know voters go gaga for a dual threat.

Alabama wants to be a zone-run and stretch attack; get a hat on a hat and let the running backs read the field and exploit spaces, with the quarterback able to pull the ball and slip out the backside if the read defender overpursues.

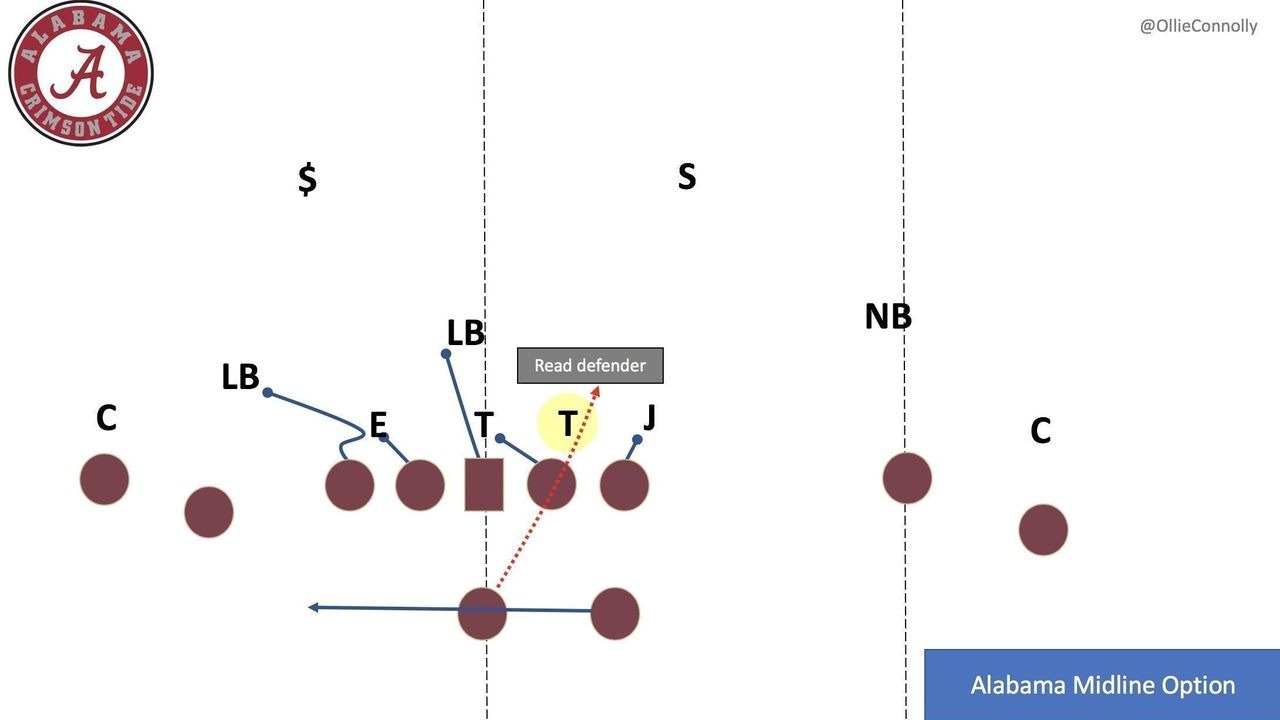

The offense's biggest change has come in the style of option, using vertical options that read an interior defender (down lineman or linebacker), making the quarterback the straight-line option, with the running back picking up the perimeter role.

Locksley's cup of tea is a basic midline read:

It works the same as an end read: If the defender crashes to the mesh point, the quarterback pulls the ball and keeps it. If the defender sits, the QB hands the ball off to his back, and a defender has been blocked through a read, making the play a 10-on-10 contest.

Edge defenders are used to the option. It's their bread and butter these days. Not inside guys. They're used to being menaces who only see the quarterback's eyes when they've buried him into the turf. Tease them with a free path to the ball and they'll jump all over it.

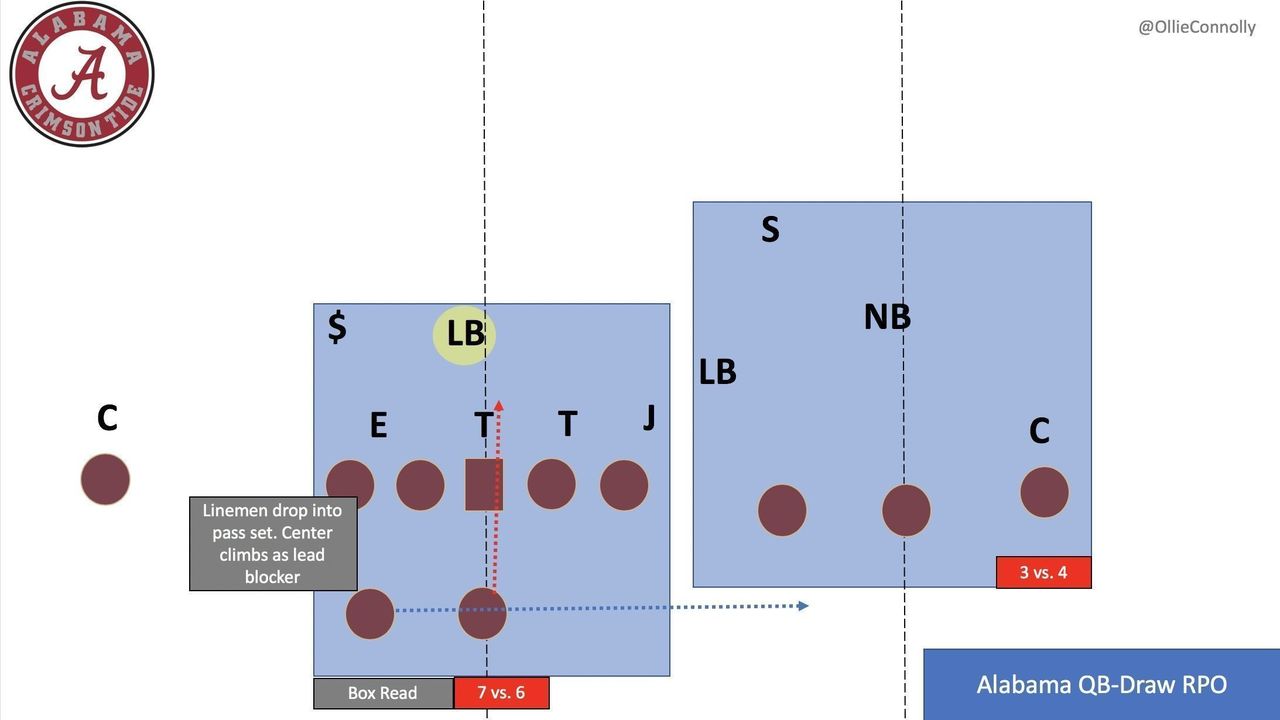

It's been fun to watch the offense shapeshift. Now it's all about the quarterback run and how that propels the traditional ground game. Even the Tide's run-pass option (RPO) package gives the quarterback a straight-line option. One of the most common is a swing pass tagged with a quarterback draw box read:

The running back charges across the formation toward a three-receiver set. The quarterback reads the box. If the defense stays static, the quarterback has numbers on the perimeter. Easy yards. If a defender tracks the flaring back, the QB pulls the ball and runs it straight ahead.

Tagovailoa must be licking his chops. I'm getting giddy just thinking about it. He's a more slippery runner than Hurts. Alabama used Hurts on more direct short-yardage runs. He'd take a direct snap and peel in behind a pulling guard.

That's not Tagovailoa's game. He's better creating for himself in space than being told which gap to attack. He has the vision and speed to do damage in the open field.

It's something that separates him from the rest of the Heisman pack. There are only a couple other quarterbacks in a position to put up the same volume of passing and rushing totals and contend for the national championship. If he performs in big games on the way to the playoff, Tagovailoa will be in a league of his own.

Now all he has to do is win the job.