Explaining a Hall of Fame vote and process

The Baseball Hall of Fame voting process is far from perfect. But because it's so difficult to compel 75% of any one group to agree on any one thing - that's the percentage required for immortalization in Cooperstown, New York - the membership's been kept exclusive.

There's little guidance on how to vote, and voters bring all sorts of different perspectives and biases into the process. This can be viewed as a bug or a feature, as that diversity of thought - and sometimes lack of it - keeps the Hall small. Overwhelming consensus is rare. At the very least, the Baseball Writers' Association of America, the voters and the stewards of the Hall, of which I'm a member, haven't watered down Cooperstown.

Still, while the vote will never be a perfect science, I believe we can do better as an electorate. We can think more critically and objectively about who should be in the Hall.

The ballot's once again crowded because of the difficult path to enshrinement, and deserving players will be at risk of being left out as time encroaches upon their candidacies' shelf lives. All ballots must be postmarked by Dec. 31, and the the results will be unveiled live on MLB Network on Jan. 23.

Candidates get 10 years on the ballot, as long as they're appearing on at least 5% of ballots. If they fail to be inducted, their fate is left to committees. While not a death knell - committees have selected more than half (139) of the 270 players in the Hall - it's not ideal, either.

The one rule, the one major constraint remains: voters cannot select more than 10 players. This plays a role in creating a logjam.

This is my second year as a Hall of Fame voter, and it's a more difficult vote this time. It's a crowded single sheet of paper.

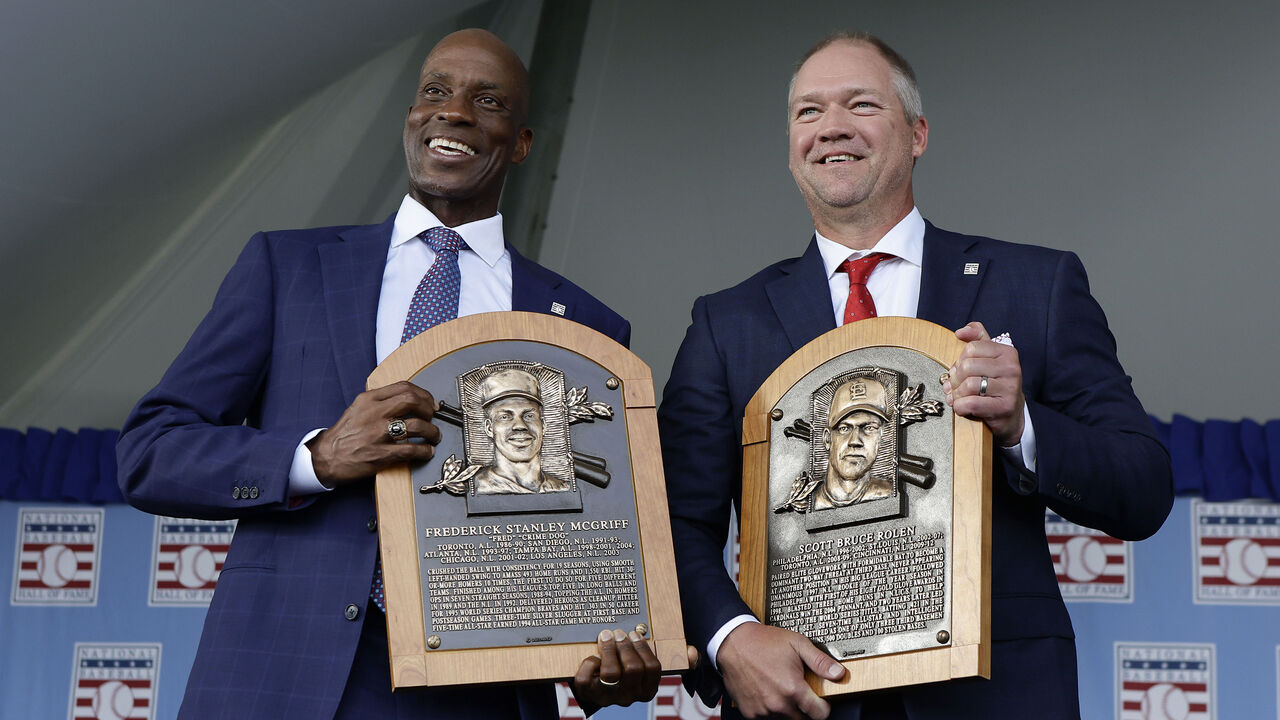

I checked 10 boxes last year - the maximum number. Scott Rolen was on my ballot and was inducted into the Hall. Jeff Kent was also on my ballot last year but fell short in his final year of eligibility.

That means I have eight holdovers, two vacant spots, and 12 first-year candidates to consider: José Bautista, Adrián Beltré, Bartolo Colon, Adrián González, Matt Holliday, Victor Martinez, Joe Mauer, Brandon Phillips, José Reyes, James Shields, Chase Utley, and David Wright.

It's difficult math.

Fans and players deserve transparency from voters, who ought to have a process and methodology they can explain and defend. It's a very small voting cohort for an institution many care about. My main goal is to root out as much bias and subjectivity as possible in my vote.

In my second year as a voter, I'm again sticking with the process I outlined last year. It's based upon a few tenets:

- Traditional statistical benchmarks can't be used as primary measures in determining who's in and who's out. The game's changed too much. Pitchers simply don't pitch as deeply into games, and strikeout rates are elevated because of pitching skill gains and changes to hitters' approach. Players must be judged against their peers, not against ghosts. That means career WAR and a player's peak (WAR7, their best seven seasons) are important measures I employ. I believe in balancing peak performance and longevity. I also employ OPS+ for hitters and ERA+ for pitchers, which adjusts for run-scoring environments and ballparks. (For pitchers, I use a couple other measures to adjust for the lack of innings in this era.) Baseball Reference's WAR isn't a perfect measure, but I like how analyst Tom Tango characterizes the metric: "Does WAR offer fact? No. Does it reflect reality? Yes." I want my vote to reflect reality as best it can.

- To determine who ought to be in the Hall, I respect large-sample precedent. Of the 17,610 major-league players to debut between 1871 and 1999, only 1.5% - 270 players - have reached Cooperstown. That's a small number. So if a player fits squarely in that group by the performance measures chosen, if one fits comfortably in that bell-shaped-curve Hall of Fame population at his respective position, he owns a strong candidacy.

- Steroid use isn't a black-or-white issue, it's a gray one. It states as much in clause "e" regarding Hall eligibility: "Any player on Baseball's ineligible list shall not be an eligible candidate." To be ineligible over PEDs, however, a player must be suspended three times. Otherwise, they're eligible. That doesn't mean a single suspension shouldn't be penalized by voters, but my view is that one suspension cannot disqualify a candidate, as the player is still on the ballot. Moreover, it's impossible to know all violators, especially before PED testing. Voters are advised to consider "character" in their voting choices, and for some, PED use is a sufficient enough violation to invoke a character clause. But the problem with that view is the Hall has always made room for "infamy," as The New York Times' Bill Pennington wrote in 2013, from Ty Cobb, to Cap Anson, to Orlando Cepeda. MLB historian John Thorn told Pennington: "Plaster saints is not what we have in the Hall of Fame. Many were far from moral exemplars."

These are my eligible holdovers; I believe they all remain worthy candidates:

- Bobby Abreu

- Carlos Beltrán

- Todd Helton

- Andruw Jones

- Manny Ramirez

- Alex Rodriguez

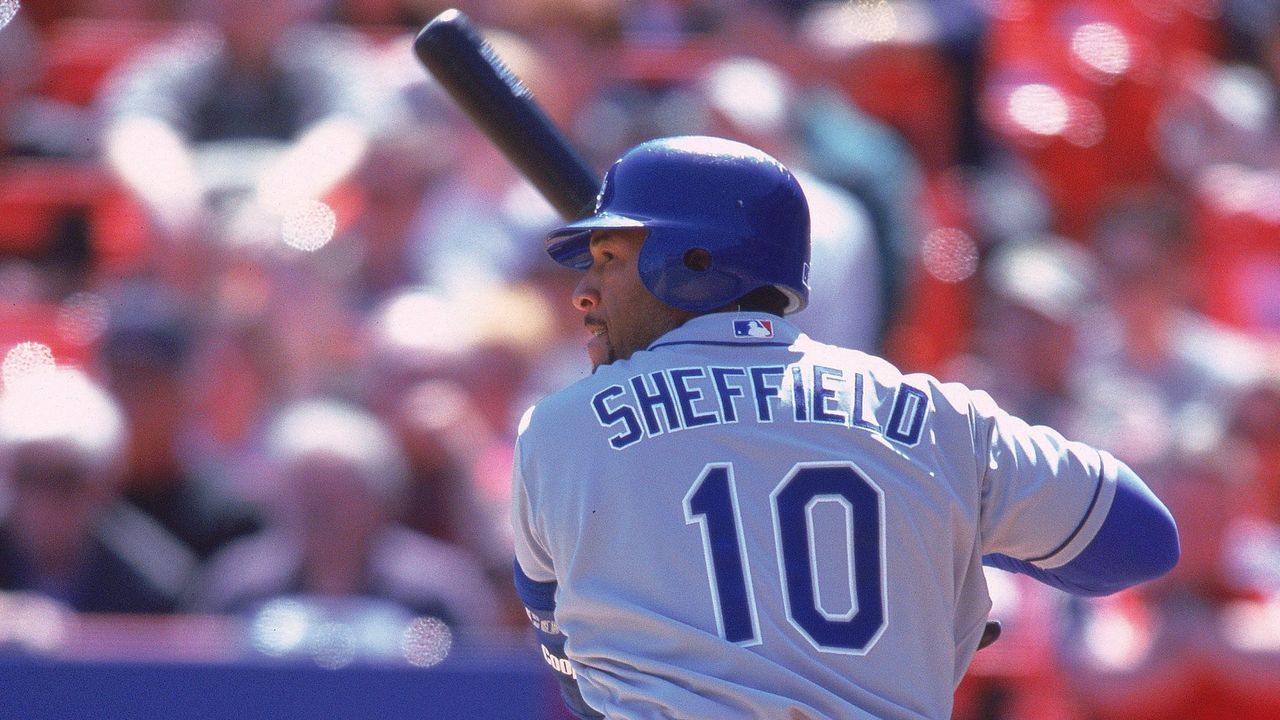

- Gary Sheffield

- Billy Wagner

For a full explanation of last year's ballot and the above candidates, please read last year's piece on my rookie ballot. But I'd like to share a few notes on the holdovers:

- Among the group, Jones is the only player who didn't fit within a standard deviation of the Hall of Fame median performance at his respective position in all measures. He fit within the two WAR measures, but fell short in OPS+ (while including OPS+ might appear to be double-counting, I wanted to place more weight on offensive performance, which can be measured with more certainty). That said, Jones owns the greatest defensive WAR total in the game's history (24.2 WAR), and his glove clearly passed the eye test, too. He also clears the 60-WAR threshold (62.7 WAR). That's important: 126 position players have reached 60 WAR and 89 are in the Hall. Even though WAR's a relatively new measure, it's done a good job reflecting past reality.

- To address steroid users, I discount the career record of those who tested positive or admitted to use by 10%. It's not a perfect process, but it's an attempt to reserve the space for truly great talents who are a part of that era's history, while eliminating fringe candidates who might have been pushed over the line by performance enhancers. Ramirez, Rodriguez, and Sheffield all received 10% hits but still crossed the threshold.

- Yes, Abreu was that good. He was caught somewhat between eras, playing part of his career pre-"Moneyball" when his OBP skills (career .395 mark) weren't fully appreciated. But he wasn't just an OBP bat. From 1998 to 2010, no MLB right fielder produced more WAR than Abreu. Only Larry Walker produced a better OBP, and only Ichiro Suzuki stole more bases during that time. Abreu is one of six players to hit at least 288 homers and steal 400 bases, and he ranks 15th among all right fielders in WAR7.

Those are my incumbents.

Now, who from this year's class deserves a vote?

Let's start with Beltré.

Not only does Beltré exceed traditional measures like reaching 3,000 hits (3,166), he also ranks third all time among third baseman in WAR (93.5) and 14th in peak performance. An elite defender, he played 2,759 games at third base, second only to Brooks Robinson's 2,870. He should be a lock to enter the Hall.

Beltré takes up one of my open slots, and fits near the top of the list if ranking it in order.

That leaves one open spot.

Chase Utley is within a standard deviation of the median WAR and OPS+ among Hall of Fame second basemen, and is above the Hall median for his peak. His top seasons were special, averaging 27 home runs a year, a .298/.388/.523 slash line, and a 133 OPS+ as a middle infielder from his age 26-31 seasons. Seven of the eight second basemen to rank ahead of him in WAR7 are in the Hall, with Robinson Canó not yet on the ballot.

Utley also ranks fifth in WAR among all players eligible on the ballot. For me, he's another lock in his first year.

Then there's Mauer, another first-year player expected to have an excellent chance at induction.

Mauer's candidacy isn't without flaws. He was behind the plate for only 7,883 innings, far less than some primary catchers who've entered the Hall; that volume ranks 44th among all catchers since 1990. And he wasn't an elite performer at first base, where he spent the close of his career.

But Mauer did enough at catcher to earn a spot.

His WAR7, all from years when he was catching, trails only Gary Carter, Johnny Bench, Mike Piazza, and Ivan Rodriguez at the position. They're all Hall of Famers. If we include only the seasons when Mauer was catching, he'd still be within a standard deviation of the median Hall of Famer career WAR at the position. While batting average is largely devalued today, it fueled his elite on-base skills. He was a .306 career hitter and is the only catcher to win three batting titles.

Those three are first-ballot locks for this voter.

There were some other close calls. David Wright was an excellent player who fits within a standard deviation of Hall third basemen in WAR/WAR7/OPS+ and deserves further consideration. But among this position-player group, he falls below a career WAR of 50, while only the catcher, Mauer, falls below 60.

My issue with adding three new players to my ballot is that I retained eight. One holdover must be cut.

My final three spots came down to Abreu, Beltrán, Sheffield, and Wagner. And it's here where I'm voting strategically.

Let's start with Wagner.

Relievers are special cases, and they should have to clear a high bar. They're generally failed starting pitchers, after all.

They'll almost always lose the volume game. Only the rarest relievers like Mariano Rivera will compile career WAR comparable to a Hall candidate who's a position player or starting pitcher. Wagner's 15th all time in reliever WAR (27.7) and only six of the relievers above him are in the Hall.

Wagner would also represent a first in terms of lack of innings.

No pitcher who spent the majority of his career in the AL or NL entered the Hall with fewer than 1,000 innings pitched. Bruce Sutter (1,042 innings) and Trevor Hoffman (1,089) are the closest. Wagner finished his career at 903 innings.

But per inning, few have been better.

Wagner's better than the median of the small group of relief pitchers in the Hall in terms of WAR7 and ERA+, and within a standard deviation of career WAR among Hall relievers.

In fact, his career 187 ERA+ trails only Rivera - among all pitchers - in the Live Ball Era.

Failed starters or not - Wagner never started a major-league game - relievers play an integral role in the modern game.

Relievers' candidacies take a leap forward if we evaluate them also by win probability added (WPA), which adds up the change in win expectancy from one plate appearance to the next. It essentially measures how much impact a player had on game outcomes, performance not independent of game context. Relievers pitch in more higher-leverage innings, so some can have nearly an equal outcome on game results over the course of a season or career.

From 1995 to 2010, Wagner ranked 11th in WPA among pitchers. Rivera ranked first followed by Randy Johnson, Pedro Martinez, Roger Clemens, Roy Halladay, Curt Schilling, Greg Maddux, John Smoltz, Hoffman (another reliever), Johan Santana, and Wagner.

That's a heck of a list and speaks to how dominant Wagner was when games mattered most. He gets my vote again.

I also checked the box next to Sheffield's name. Not only because of the iconic bat waggle and lightning-quick swing that launched 509 home runs - and probably sent another 300 just foul - but because even with a 10% PED penalty, he still falls within a standard deviation of the Hall of Fame median of WAR, WAR7, and OPS+ for a right fielder. However, his resume is the weakest among the 11 players I deem to be Hall worthy.

Still, he owns a greater career WAR than David Ortiz - whose own career is clouded by PED allegations - Vladimir Guerrero Sr., Willie Stargell, and Harmon Killebrew. And because this is Sheffield's final year on the ballot, that distinction serves as something like a tiebreaker.

For me, Abreu's a Hall of Famer whose candidacy deserves more time to be considered by the electorate. He's in danger of falling off the ballot as it becomes more crowded, so I'm using one of my final checkmarks on him.

The cut is Beltrán.

Like with steroids, handling on-field cheating is another difficult matter. And Beltrán was involved in one of the greater on-field cheating scandals in the game's history.

Now, there's no precedent for banning sign-stealers. As brazen as the scheme was, devised by Beltrán and executed by the Astros, MLB didn't discipline those players. I do think Beltrán's career should be discounted in the spirit of invoking sportsmanship and character demerits, as is done for PED users, and his resume becomes less robust as a result. But even with a similar PED-user penalty, he's Hall worthy. I plan to vote for him again in future years.

Unlike Sheffield and Wagner, who are running out of time, or Abreu, who's in danger of falling off the ballot, Beltrán is only in his second year of eligibility and doesn't appear at any risk of falling off, earning a 46.5% vote last year.

Remember: it's not a perfect science. Some nuance, even with statistical guides, is required.

My 2024 selections:

- Bobby Abreu

- Adrián Beltré

- Todd Helton

- Andruw Jones

- Joe Mauer

- Manny Ramirez

- Alex Rodriguez

- Gary Sheffield

- Chase Utley

- Billy Wagner

Overall, my ballot's again extremely hitter heavy, but there's simply a lack of Hall-worthy pitchers by my measures.

Andy Pettitte and Mark Buehrle are stronger candidates than Colon and Shields, but their peak (WAR7) performances fell short - and they aren't above the Hall median in any performance category.

While Pettitte, Buehrle, Sheffield, Jones, and Abreu all had similar overall WAR production, Jones was above the Hall average in center field in terms of peak performance, Abreu was above the Hall median in OPS+, and Abreu was a better player in terms of OPS+ versus the pitchers' ERA+ marks.

Is my ballot too large? I don't believe so. If anything, ballots are becoming too tight.

Writers have elected fewer than 1% of players (0.074%) to debut in the 1990s, the lowest overall induction rate of any decade. Writers have always been a tough crowd since they started voting in 1936, electing only 131 players to date. The committees will likely help fill voids, but since the 1960s, fewer and fewer players are getting in. Hall induction rates have decreased each decade since the 1950s (2.03%). The 1890s have the greatest percentage of Hall of Famers (2.46%) and the 1920s are next (2.38%). Are players getting worse? I don't believe so.

It's increasingly a small Hall in relative terms. More deserve to be included, and this is one small effort to help crack open the gates a bit more for those deserving entry.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.