How baseball Hall of Fame voting trends are evolving

This year's Baseball Hall of Fame vote figures to be one of the more interesting ones when results are revealed Jan. 25.

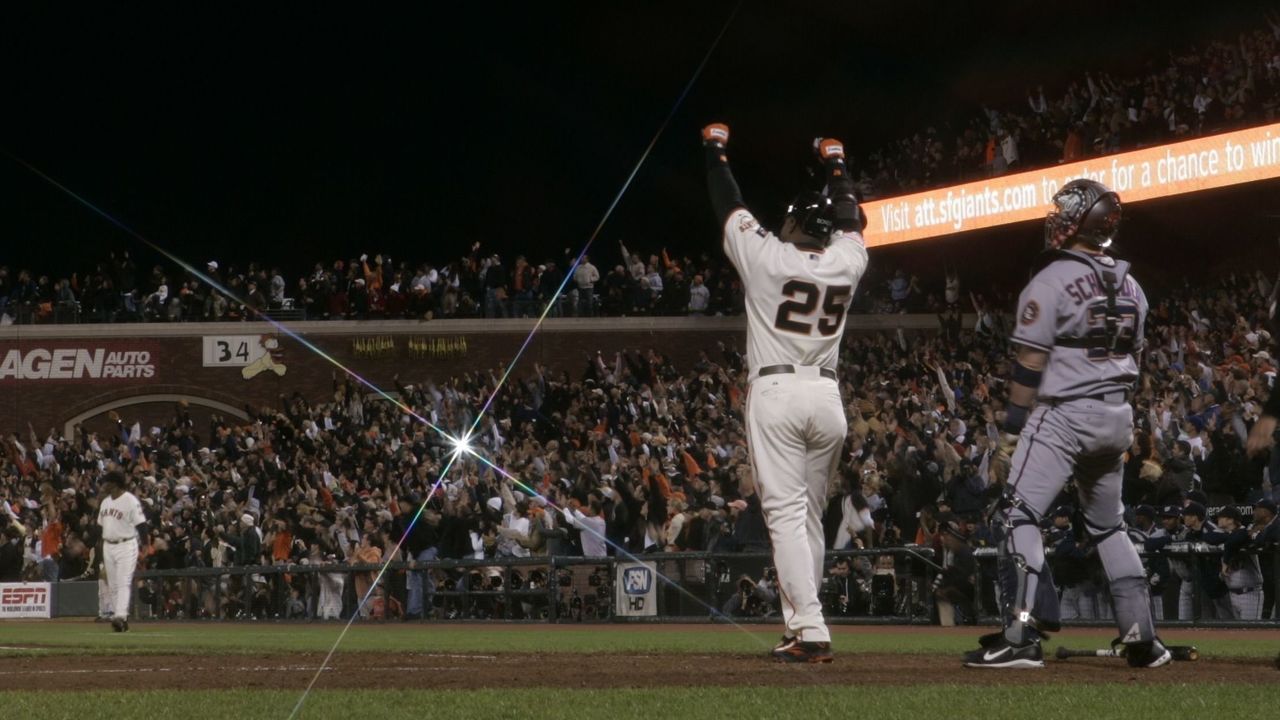

Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, and Sammy Sosa, superstars whose careers were tainted by suspicions of performance-enhancing drug use, are in their 10th and final year of consideration by voters from the Baseball Writers' Association of America. Bonds' and Clemens' candidacies are gaining traction.

A player needs to be selected on 75% of submitted ballots to earn the call to the Hall, and Bonds and Clemens are inching up. Bonds received a 61.8% vote share last year, while Clemens sat at 61.6%. Those rates are much higher compared to their 2013 ballot debuts, when Bonds received 36.2% of votes and Clemens 37.6%. If they don't get in on the writer vote this year, their fates will be left to era-specific committees to decide in the future.

Their controversial cases have clogged up the ballot for a decade, and either way - with their removal or admittance - the logjam will be reduced next year. (Voters can select no more than 10 players on their ballots, a constraint many want eliminated.)

As the vote gradually moves beyond these high-profile PED cases, this year's vote is also interesting because the Hall process and the electorate are evolving. The Hall has become more difficult to enter in recent decades, too exclusive in the context of historical precedent. As a result, modern-era players have become underrepresented as a percentage of Hall inductees. But recent trends could help reverse that.

In MLB history, 1.52% of all players to debut between 1871-1999 have reached the Hall. The rate ran as hot as 2.46% in the 1890s, and 2.38% in the 1920s, but declined every decade since the 1950s, cooling to 1.17% in the 1980s and 0.69% in the 1990s, the lowest on record. No player to debut in the 2000s is yet in the Hall.

From 1871 through 1939, 1.79% of all players to debut reached the Hall. From 1979-99, the rate stands at 1.03%.

To understand how the Hall is evolving and how modern players' odds might be improving in the future, theScore spoke with Ryan Thibodaux, who's been tracking publicly released ballots and voting trends since 2014.

Thibodaux said one of the most interesting things about the electorate is how it has decreased in size. To earn a Hall of Fame vote, writers have to be BBWAA members for 10 years. But a new rule established in 2016 removed voters who hadn't been active members for 10 or more years.

"That really makes a huge difference, especially when most of the people who have left the electorate are the older voters," Thibodaux said. "Certainly they are more anti-PED than the younger voters. They also don't vote based on analytics as much. They tend to be smaller-Hall style voters."

The number of voters dropped from 549 in 2015 to 440 in 2016. After the ballots peaked at 581 in 2011, they've resided between 440 and 397 since the rule change.

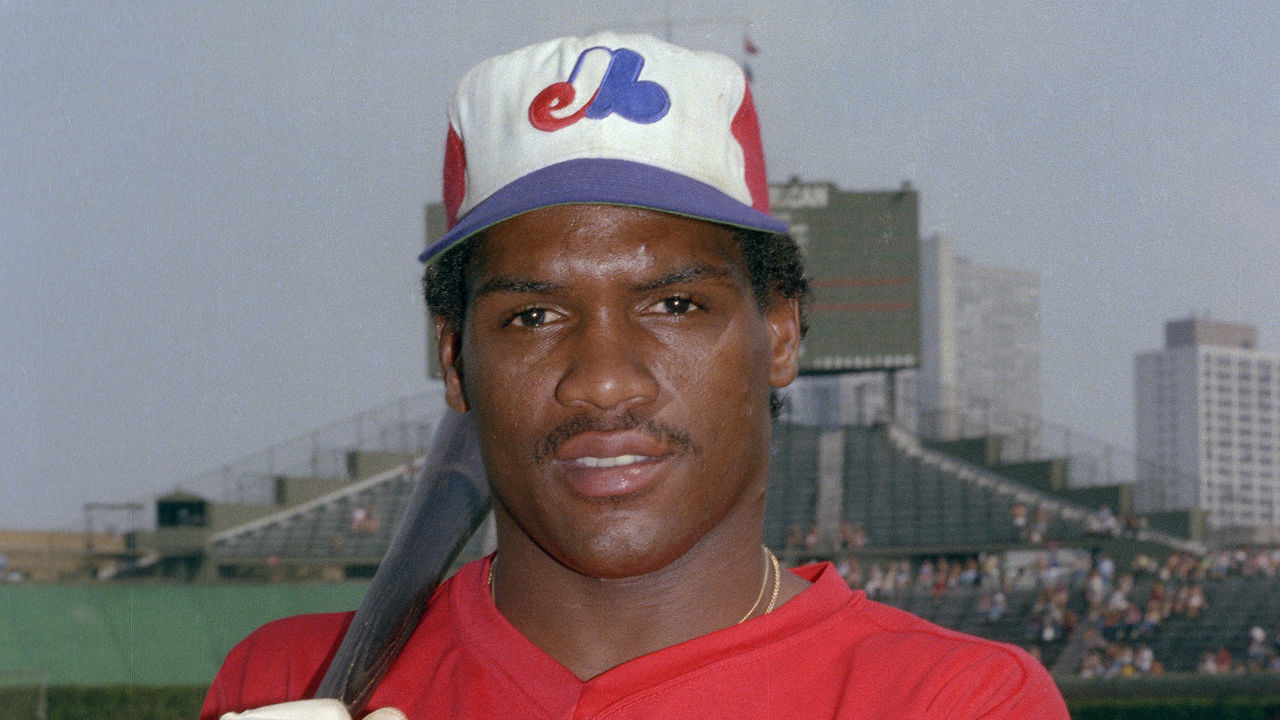

Since 2016, Thibodaux points to Tim Raines, Edgar Martinez, and Larry Walker as evidence of change in voting criteria. None of those three reached 3,000 hits, which has long been an important consideration needed to gain entrance to the Hall as a batter.

David Ortiz, another candidate with fewer than 3,000 hits, has a chance to be a first-ballot Hall of Famer.

Will David Ortiz be a first-ballot Hall of Famer? Some of the projection systems out there disagree. Here's the tracking through 140 ballots for Ortiz this year compared to Pudge Rodriguez in 2017 (when he was elected with 76.0%) and Jeff Bagwell in 2016 (came close at 71.6%). pic.twitter.com/QR5BACKCme

— Ryan Thibodaux (@NotMrTibbs) January 11, 2022

The problem with such accumulative measures - like 3,000 hits or 300 wins for pitchers - is that they're no longer valid milestones in the modern game, in which starters throw fewer innings and hitters walk and strike out more.

"I'm not sure any of them would become Hall of Famers if that rule change hadn't been made," Thibodaux said of Raines, Martinez, and Walker. "It's going to continue to make a big difference for candidates like Scott Rolen (52.9% last year), Todd Helton (44.9%), Andruw Jones (33.9%), those types of candidates who might not have made the push they seem to be making."

Perhaps it means those players who debuted in the 1990s, who are underrepresented to date in the Hall, have a greater chance of gaining entrance. Even players who may have had trouble in the past earning the 5% of votes needed to remain on the ballot are being re-evaluated by new metrics and are becoming more potent candidates. Players from the 1970s and 1980s who'll be re-evaluated by future committees may also find new favor.

This year, though, there's one big question: Will Bonds and Clemens get in on their last attempt? It's going to be close.

Thibodaux, who's collected more than 150 ballots to date, projects the pair to likely finish above the 75% mark on those ballots known before the Jan. 25 announcement. The complicating variable is the private ballots, which are usually much cooler on the PED group. Bonds and Clemens earned about 42% approval on those ballots last year.

Over the last three years, 84% of ballots have been made public, although only slightly more than half are revealed before the vote is announced. Others come in after in the fact.

Year over year tracking through 140 ballots for Barry Bonds (Clemens is similar), Scott Rolen, Curt Schilling, and Todd Helton: pic.twitter.com/2BrNzLrH37

— Ryan Thibodaux (@NotMrTibbs) January 7, 2022

Another Hall modeler, Scott Lindholm, projects the BBWAA will not elect any players for a second straight year. Much of the reason is the PED-tainted candidates.

Despite the demographic trends among Hall voters, they still seem to be slowly adapting from mostly examining counting numbers - like 3,000 hits, 500 home runs, and 300 wins - to seeking additional context and judging candidates within their era.

"What I see from (voters), they are definitely making that adjustment," Thibodaux said. "Leaving aside his off-the-field things, we know when Curt Schilling came on the ballot 10 years ago you saw a lot of discussion about how 216 wins were not enough, and he didn't make the cut because of the performance. You almost never hear that argument made anymore. … Some are not going to vote for him because of off-the-field things, but it's rare to see anyone make the case that he wasn't a Hall of Fame-caliber pitcher. That's certainly a shift from when he came on the ballot."

Schilling was the top vote-getter last year (71.1%) after debuting at 38.8% in 2013.

"I think that shift happened when Mike Mussina came on the ballot," Thibodaux said of Mussina, who amassed 270 wins. "It took him a few years to get into the Hall of Fame, but he made it eventually. I think if Rolen had appeared on the ballot a few years earlier, he might have had a problem staying on (the ballot) for a couple of years, like Kenny Lofton … because his case is so dependent on advanced metrics and looking past counting stats. It looks like he might be in position as soon as next year to get elected. So I definitely think that shift has happened, and happened pretty quickly the last few years."

Perhaps that shift will continue, widening the Hall, which has become an increasingly exclusive club.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.

HEADLINES

- Kaprizov breaks Wild's all-time goals record in win over Lightning

- Stars extend franchise-record winning streak to 10 with romp over Flames

- Predators' O'Reilly exits with cut near eye, expected to be OK

- Grizzlies' Edey undergoes season-ending ankle surgery

- Ant goes off for 41 as T-Wolves top Grizzlies for 4th straight win