Remembering the college football game that paused a world war

On Nov. 11, 1944, while American soldiers pressed through mud and artillery fire in a bid to drive occupying German forces out of France, Col. Russell "Red" Reeder sat in his wheelchair an ocean away from the battle, observing his first Armistice Day as an amputee from the sideline of an Army football game.

Reeder's prime vantage point for the late-season clash with Notre Dame befitted his standing as a West Point great: an infantry commander in Normandy who, two decades earlier, had won campus-wide renown for his exploits on the gridiron. In 1925, Reeder's timely drop-kick field goal provided the insurance points that cinched a narrow win over Navy. His contributions to the D-Day invasion in June 1944 earned him a medal for valor - at the cost of his left leg, ravaged by a German anti-tank shell and later removed in a Washington hospital.

By November 1944, Reeder had recovered enough that he could join Gen. George Marshall on his private plane for a short trip to New York. At Yankee Stadium, he watched Army author the largest defeat ever inflicted upon Notre Dame: a 59-0 thrashing that preserved the Cadets' No. 1 spot in the national rankings.

At 11 a.m. that morning, thousands of New Yorkers had massed in Madison Square for a silent tribute to U.S. troops everywhere. Another expression of gratitude was to follow. At the final whistle, Army quarterback and captain Tom Lombardo exchanged a quick word with the referee and then trotted to the sideline where Red Reeder sat, a white blanket hiding his wound from the world. Lombardo shook Reeder's hand and gave him the game ball.

Army's beatdown of the Fighting Irish, combined with Notre Dame's 32-13 loss to Navy the week prior, set the stage for a titanic college football game played 75 years ago Monday. The participants, according to The Associated Press' authoritative poll, were the two best teams in the country. Meeting annually on the final day of the season, they formed the signature rivalry of a bygone age, a period in which the stature of the collegiate game eclipsed that of the pros thanks in no small part to the competitiveness and mystique of America's military academies.

Those superlatives only begin to explain the magnitude of the 1944 Army-Navy game, the apex of a revered on-field feud set against the backdrop of bloodshed abroad. For a fuller understanding of the matchup's meaning, consider the telegram Gen. Douglas MacArthur sent postgame from the Philippines to the victorious coach: "WE HAVE STOPPED THE WAR TO CELEBRATE YOUR MAGNIFICENT SUCCESS."

In the fall of 1944, as World War II entered its sixth and decisive year, the Allied campaigns to liberate Europe and subdue Japan in the Pacific theater had stalled; victory appeared attainable but remained elusive. In the U.S., college football doubled as go-to a training ground for young men who'd soon be called upon to serve - to quote a former Navy coach, it was the closest form of competition "to actual war" - and a worthy distraction for weary civilians, nearly all of whom had personal ties to soldiers at the front.

That Dec. 2, millions of Americans at home and abroad set their radio dials to Army-Navy, in simultaneous search of a break from history's deadliest conflict and a reminder of why that fight was being waged.

"The Army-Navy game symbolized the continuation of peacetime rivalries in a time of national crisis," historian Randy Roberts wrote in "A Team For America," his 2011 book about the buildup to the contest. "In a very real sense, it stood for exactly what Americans most desired, a return to the normality of American life."

It also promised to be a hell of a spectacle. For a few years following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. mobilization for war had the ancillary effect of directing a critical mass of eligible football talent to so-called service teams: training centers that competed in NCAA action as their players awaited deployment. By the end of the 1944 season, these teams comprised exactly half of the AP Top 20.

Army and Navy not only split the difference between wartime training centers and traditional colleges, they predominated over any and all football opponents throughout 1944. Powered by the Heisman Trophy-finalist backfield duo of Felix "Doc" Blanchard (nicknamed Mr. Inside) and Glenn Davis (Mr. Outside), Army entered the game against Navy with an 8-0 record. It had outscored its competition 481-28, and in no game had the Cadets' defense allowed more than seven points.

"Never before had a college football team authored such astonishing credentials," reads a recap of the season in Army's football media guide. "Many college football historians contend the 1944 Army squad ranks as the finest college club ever assembled."

It took a lineup of such prolific quality to inspire confidence that Army could snap a five-year losing skid to Navy. The Midshipmen had shut out Army four times since the start of the war. In 1944, Navy counted on its formidable offensive line - anchored by All-American Don Whitmire, a transfer from Alabama - to bulldoze holes for running back Bob Jenkins, a kind soul who enjoyed catching butterflies off the field even as he trampled defenders on it. That formula had led Navy to a 6-2 record, including three blowout wins over ranked opponents, ahead of the season finale.

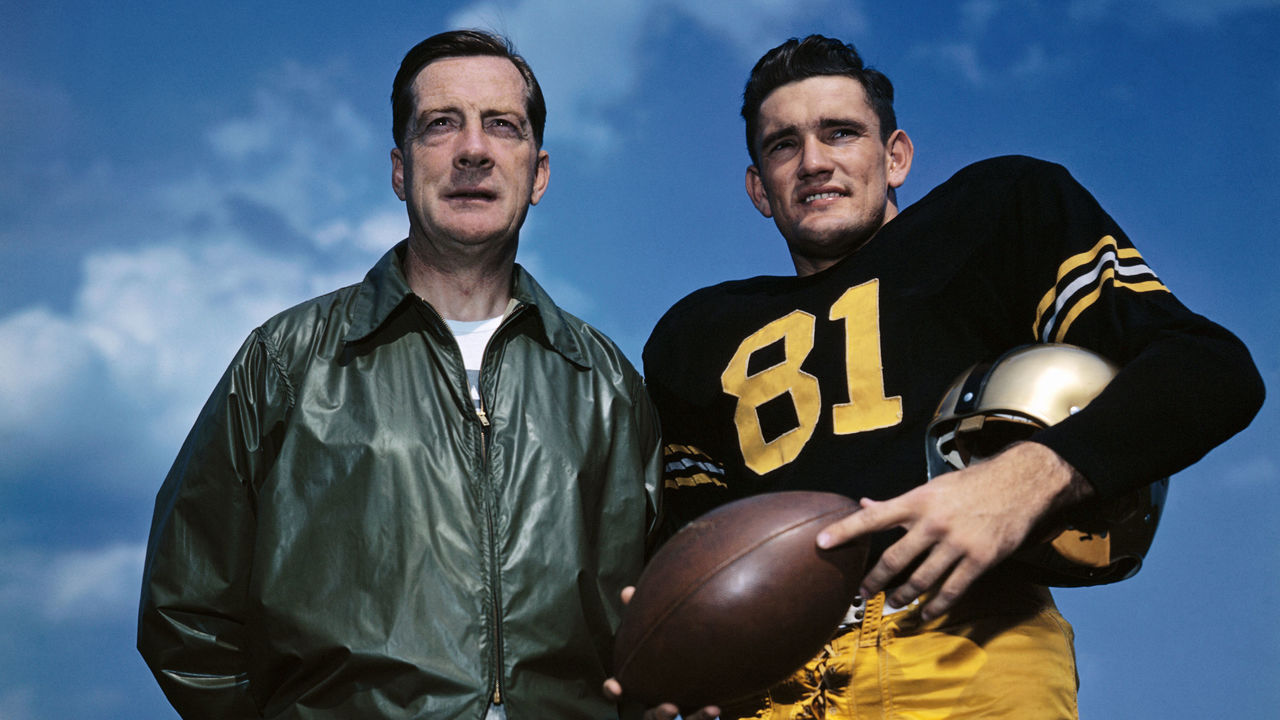

If Navy's winning streak in the series was an acute psychological edge, the coaching matchup may have been the locus of Army's greatest advantage. On the Navy side, Oscar Hagberg was a rookie bench boss, busy for much of the war commanding submarines in the Pacific. Army's Earl Blaik, a former star lineman at West Point, had spent those years resuscitating a moribund program that went 1-7-1 in 1940, the season before his hiring.

In appearance and demeanor, Blaik embodied the Platonic ideal of a football coach. His jaw was square, his red hair trimmed close to the temple. He neither drank nor cursed. He ate meals at his desk under a picture of Gen. MacArthur on the wall behind him. He organized his days into 15-minute increments to be maximally efficient, a priority that carried over to his management of the 1944 season. Rather than man the sideline for a Nov. 4 matchup with lowly Villanova, Blaik absented himself from the game - an 83-0 Army victory - and boarded a train to Baltimore to scout Navy's showdown with Notre Dame.

Nothing gnawed at Blaik more than losing, especially to a particular archrival. On Jan. 1, 1944, he rang in the new year by summoning his staff to an 8 a.m. meeting. There, as Blaik later detailed in his autobiography, he emphasized to his hungover assistants "that this was the first day of the year in which we were going to beat Navy, and we must get to the job without delay."

Up until mid-November 1944, the Army-Navy game was set to be held in Annapolis, Maryland at Thompson Stadium, the 12,000-seat venue on Navy's campus. The size of the stadium, it soon became clear, wouldn't come anywhere close to sating public demand. When U.S. government officials, recognizing the cash cow on their hands, brokered the game's relocation to Municipal Stadium in Baltimore, 66,659 people bought war bonds for the right to also purchase a ticket.

Intriguing storylines proliferated in the days leading up to Dec. 2. Notre Dame, vanquished by Navy and Army in successive weeks, asked each member of its starting lineup to predict the outcome; eight of 11 players backed Navy to win. The day before Army left for Baltimore, Blaik dodged a question about the health of lineman Dick Pitzer, who'd injured his leg in an intrasquad scrimmage the previous weekend. ("Apparently, Pitzer's a military secret," The New York Times quipped.) Blaik was more candid in conceding this Navy squad was the best he'd ever seen.

The morning of the game, as 3,000 Navy midshipmen made the quick steamer trip to Baltimore through the Chesapeake Bay, some 2,500 Army cadets arrived after two choppy days aboard an ocean transport ship, a vomit-inducing voyage from West Point meant to prepare them for a possible future journey to war. Amid suspicion that German U-boats lurked less than 100 miles from the coast, three Navy destroyers had been deployed to shepherd the ship to safety.

At the stadium, both sets of students marched onto the field in procession before storming into the stands, where a host of military luminaries - including Gen. Ben Lear, chatting with disabled veterans at the 50-yard line, and Marshall himself, shivering in the third row - awaited kickoff. An armed limousine escorted Navy's mascot, Bill the Goat, onto the field to exchange pleasantries with Army's mule. Shortly after, the sellout crowd received some news: The war-bond drive connected to the game had raised a cool $58.6 million.

"Not a bad haul for Uncle Sam in one cold afternoon," sportscaster Ted Husing said on a video recap of the proceedings.

Navy tackle Bo Coppage, speaking to The Philadelphia Inquirer years later, was confident "nearly every radio in America" was tuned to the game. Coppage's opponents were equally attuned to the magnitude of the broadcast's reach. Writing from the South Pacific, Army Gen. Robert Eichelberger cabled a message to Blaik that the coach relayed to his roster: "Win for all the soldiers scattered throughout the world."

The Cadets' odds of doing so increased on the game's very first drive when their All-American lineman, Joe Stanowicz, concussed Navy's Jenkins with a clothesline that went unpenalized. Whitmire, the menacing Navy lineman, followed his running back to the sideline in the second quarter, felled by the combination of a wrenched knee and a block administered in the vicinity of his chinstrap. Their departures typified the spirit of a violent, turnover-plagued first half, from which Army finally emerged with a 7-0 lead on a touchdown run from halfback Dale Hall.

Already the Cadets had bettered their point total from the previous five Navy games combined. The field continued to tilt Army's way early in the second half, when Stanowicz blocked a punt that bounced into the end zone, forcing a safety. And yet the game remained within Navy's grasp for a while. In Jenkins' absence, 148-pound running back Hal Hamberg began to pierce Army's defense for modest, drive-extending gains. Late in the third quarter, another back, Clyde "Smackover" Scott, fulfilled the promise of his nickname by plunging over the goal line for a 1-yard score.

The scoreboard read 9-7 for Army when Blanchard and Davis took over. In an era in which players played both offense and defense, Davis intercepted a misaimed pass from Jenkins - whom Hagberg had briefly reinserted despite his pounding head - and carried the ball to midfield. The turnover cued Mr. Inside's breakout moment. On a nine-play Army drive, Blanchard ran seven times for 48 yards - the final 10 manifested in a touchdown romp through the teeth of the Navy defense.

Navy had curtailed the Cadets' best and brightest for more than 45 minutes, but now the coup de grace loomed. After a Midshipmen punt, Davis took center stage in a play dubbed the California Special, a nod to his home state. Catching a rapid lateral from quarterback Lombardo in the backfield, he darted past three helpless defenders and dove to beat a fourth into the corner of the end zone. The 50-yard touchdown run extended Army's lead to 23-7.

The margin was long past insurmountable. Within a few minutes, Army clinched its share of milestones: an undefeated season, designation as the AP poll's national champion, and Blaik's long-sought, hard-fought first win over Navy. He'd soon receive that congratulatory telegram from MacArthur - the general in the Philippines and the West Point icon on his office wall - informing him that the victory had brought the American war effort to a halt.

The halt, naturally, was fleeting. Before the Cadets and Midshipmen left the field, they met in the middle to shake hands and swap well-wishes. Two days later, New York Times sportswriter Allison Danzig summarized for his readers what lay ahead: "The country can now return to the normalcy of fighting the most terrible war ever inflicted upon mankind."

Eventually, that war ended, leaving people everywhere to reckon with its staggering toll and figure out their way forward in life. So it went for the young stars of Navy and Army. Bob Jenkins injured his knee, served in the Navy for a time, and returned to Alabama to run a machine tools business. Don Whitmire became a rear admiral and helped evacuate Saigon during the Vietnam War. Doc Blanchard, the Heisman Trophy winner in 1945, later piloted 84 missions over North Vietnam. Glenn Davis, the Heisman Trophy winner in 1946, injured his knee but went on to make the Pro Bowl as an NFL rookie in 1950.

In Blanchard and Davis' last two years at West Point, Army built on its breakthrough subjugation of Navy: the Cadets won the matchup 32-13 in 1945 and 21-18 in 1946. Both results clinched undefeated seasons.

1946 was also the year Col. Red Reeder retired from active duty. From his wheelchair, he worked as an assistant athletic director at West Point, and later transitioned to a career in nonfiction writing, specializing in U.S. military history.

Six years after he handed Reeder the game ball from a 59-0 victory, Tom Lombardo was tasked with commanding a company of infantrymen in South Korea, the epicenter of a different war. On Sept. 24, 1950, he led his regiment across a sprawling valley near the southern town of Ch'ogye. Bullets bore down on them from above. Stuck for options, Lombardo called for a counterattack. He and some volunteers charged the enemy position. Somewhere in the fray, he was mortally wounded. He died on a hill at the age of 27, survived at home by his wife, his four-year-old daughter, and his eight-month-old son.

In 1962, the football field at a U.S. Army installation in Seoul was named in Lombardo's honor. At a ceremony, the commanding officer of the day read a thank-you message from Blaik, who had this to say about his old captain: "From her sons, West Point expects the best. Tom Lombardo always gave his best."

The praise would have sounded familiar to Lombardo's teammates from 1944, each of whom received a souvenir book at the end of that season. Inside was a note from their coach, saluting the players who had finally beaten Navy.

"Seldom in a lifetime's experience is one permitted the complete satisfaction of being part of a perfect performance," Blaik wrote then. "To the coaches, the 23-7 is enough. To the squad members, by hard work and sacrifice, you superbly combined ability, ambition, and the desire to win, thereby leaving a rich heritage for future Academy squads.

"From her sons, West Point expects the best. You were the best. In truth, you were a storybook team."

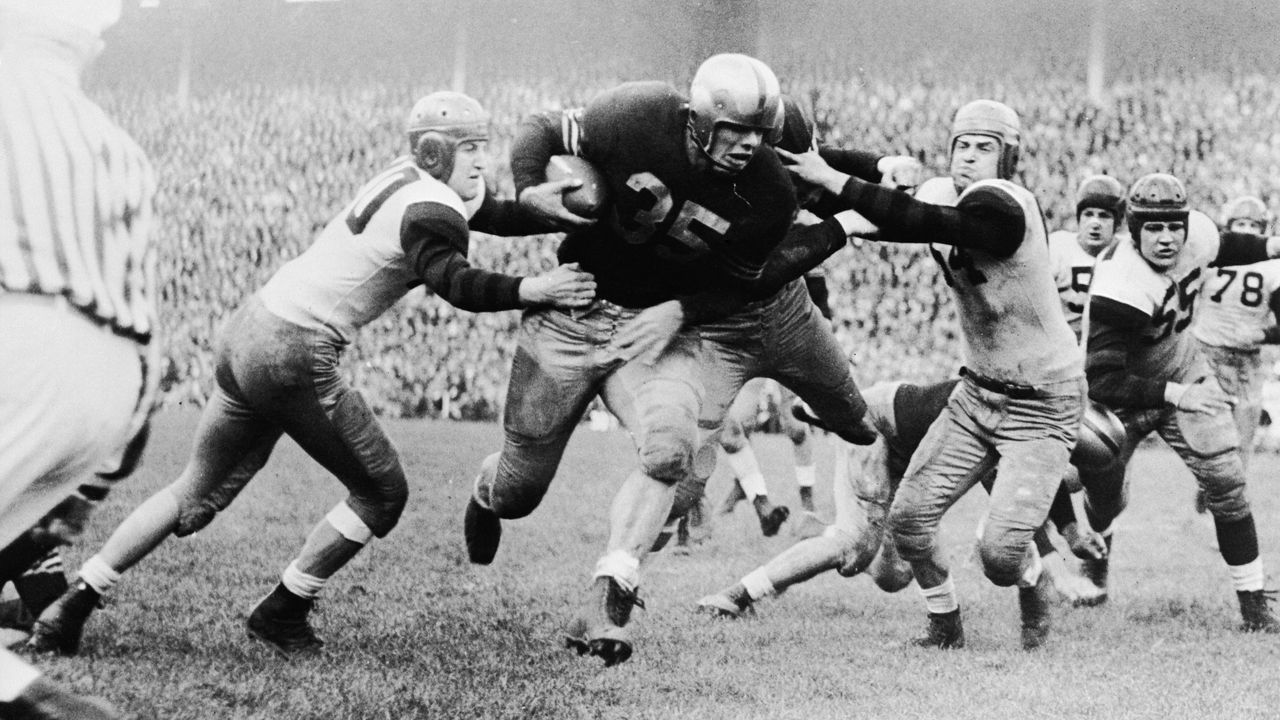

Top photo: Army players, from left, Tom Lombardo, Dean Sensanbaugher, Doc Blanchard, and Glenn Davis. Original photo from Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.

HEADLINES

- Williams entering transfer portal despite new Washington deal

- CFP semifinals picks: Will Ole Miss continue storybook run vs. Miami?

- Report: Ohio State's Tate declares for 2026 NFL Draft

- CFB portal analysis: Chip Kelly gets his QB at Northwestern

- Ex-Texas star Jordan Shipley hospitalized with severe burns from ranch accident