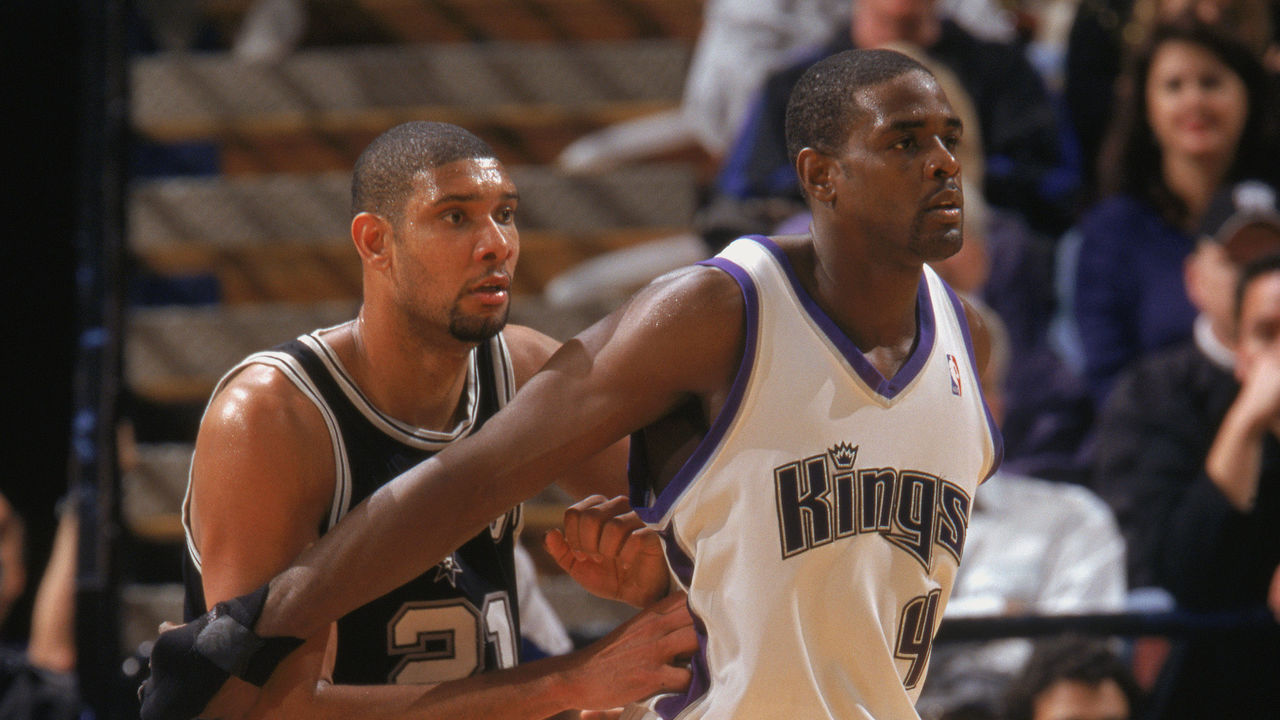

Will Chris Webber ever get his due?

Hall of Fame debates are a staple of sports arguments - whether a player's amassed the credentials to be honored among the very best in their sport is prime fodder for discussion over a beer. We're spotlighting a collection of players who we believe are deserving of the distinction but haven't yet been inducted into their sports' Halls of Fame.

For Chris Webber, being denied entry to the Basketball Hall of Fame has become an annual tradition, one that dates back to his first year of eligibility in 2013. Throughout those seven years of snubs, he's remained at or near the top of the list of the best eligible players not in Springfield.

With each passing year, though, the prospect of his eventual induction seems to become a bit more remote. Has the secretive voting body simply decided that Webber isn't a Hall of Famer? And if so, why?

Let's start with the reasons he deserves consideration. Webber was in many ways a transformational big man. He had as significant a role as anyone in shifting the power forward paradigm from a position oriented around brawn and physicality to one defined by skill and finesse. That isn't to say that Webber lacked the former traits - his game still featured plenty of power, and he could overwhelm certain opponents with force. But what made him unique among his peers was his finer skills.

He wasn't a 3-point shooter, but he possessed every other guard-adjacent tool you could ask for in a 6-foot-10 body. He could handle the ball, run the break, roast other players his size off the bounce, change speeds and directions on the drive, and, most notably, he could pass. He was one of the progenitors of the modern point forward.

Though he didn't handle the ball quite as often, Webber was something like a proto Ben Simmons with a far more complete scoring package. At his athletic peak, he was a monster in the open floor and possessed a highly effective half-court face-up game replete with shoulder fakes, spin moves, and crafty finishes, abetted by an explosive first step.

The defining stretch of his career was a five-year run between 1998 and 2003, all with the Sacramento Kings, in which he made All-NBA and finished in the top 10 in MVP voting every season. Four of those All-NBA selections were second team or better. All told, during his seven-year tenure in Sacramento, he averaged 23.5 points, 10.6 rebounds, 4.8 assists, 1.5 steals, and 1.5 blocks while helping turn the woebegone franchise into a powerhouse.

When he arrived via trade in 1998, the Kings were a 27-win team that had made the playoffs just once in the previous 12 years and hadn't had a winning season since 1982-83, when they still played in Kansas City. They made the playoffs every year Webber was there, and in each of his final four full seasons, they won at least 55 games and reached at least the Western Conference semifinals.

Being a great distributor demands both vision and touch. Webber had both in spades, along with a dash of flair that made him as fun to watch as he was effective. On top of their success, the stylistically distinct Kings were probably the most entertaining team of the early 2000s. Webber had plenty to do with that.

Sacramento's high-powered offense revolved around his playmaking instincts: his ability to grab and go in transition and to either initiate half-court sets from up top or facilitate as a double-team magnet from the post. His appetite for running the break (either as a ball-handler or a trailer filling the lane) and his willingness to sling three-quarter-court outlet passes allowed the Kings to push the tempo before doing so was really in vogue. In four of the five aforementioned seasons, they ranked first in the NBA in pace; they ranked second in the other.

Plenty of other factors contributed to the Kings' ascent at the turn of the millennium: Peja Stojakovic's emergence as a 6-foot-10 sharpshooter and unicorn in his own right; the flashy point guard play of Jason Williams and later the steady point guard play of Mike Bibby; Doug Christie's dogged defense; Vlade Divac's own brand of big-man passing genius. But in their best seasons, Webber was their most important player - the guy who tied everything together. The franchise has yet to win a playoff series since trading him midway through the 2004-05 campaign.

Though they'll perhaps always be seen as a Could Have Been because of their inability to fully cash in - especially in 2001-02, when they won a league-high 61 games - those Kings were among the most memorable teams of the decade. In Mike Prada's Titleless bracket, they were voted one of the four best teams to never win a championship.

That could vindicate Webber or damn him, depending on how you look at it. His legacy is clouded by a critique that he quailed in big moments, a charge that's typically boiled down to two particular disasters: the unavailable timeout he called in the national championship game in his final season at Michigan in 1993, and his disappearing act in the fourth quarter and overtime in Game 7 of the 2002 West finals against the Lakers.

There were other, lesser high-leverage letdowns. His postseason resume as a whole is underwhelming compared to most Hall of Famers and didn't measure up to his regular-season standards. None of the non-Kings teams he played for except the 2006-07 Pistons, for whom he played a bit part, made it past the first round. There are legitimate criticisms of his style and overall body of work. He never defended as well as his physical tool set suggested he could. The gaudy steal and block numbers he put up were more a product of his penchant for shortcuts than a reflection of his acumen or commitment at that end of the floor.

One can pick nits about intangibles, like the fact that he wasn't always the most agreeable teammate. After the Warriors traded the pick that became Penny Hardaway (along with three future first-rounders) in order to move up and draft him first overall in 1993, Webber forced his way out of Golden State after just one season amid mutual discontent with coach Don Nelson. He wore out his welcome in Washington before settling down in Sacramento and then had a rocky post-Kings stint in Philadelphia.

His case also suffers from a lack of durability and longevity. Webber always struggled with injuries; he had just six seasons in which he played 70 or more games, and he averaged just 55 per season over his 15-year career. He tore his meniscus in Game 2 of the 2003 West semis against the Mavericks - a hotly contested series that the 59-win Kings lost in seven games - and subsequently underwent microfracture surgery. That sapped his explosiveness and prematurely ended his prime, turning him into an earthbound big who was often relegated to jump-shooting on offense and had to be shifted to center on defense.

Even in his prime, some advanced metrics downplayed Webber's effectiveness, mainly because efficient scoring was never his bag. He finished his career with a 51.3% true shooting mark, well below average for a big man - even one who was less interior-oriented than most and played through basketball's version of the dead-ball era. Basketball Reference's Hall of Fame Probability calculator gives him just a 14.6% chance of getting in based on his NBA exploits alone.

The Naismith Hall of Fame is not limited to NBA exploits, of course, but trying to factor Webber's college career into his case doesn't simplify things at all. On the one hand, if we look past the infamous timeout call, we can say beyond a doubt that he was the best player on the Fab Five, the iconic Wolverines team that made the national championship game in both of Webber's seasons there. On the other hand, according to the official record, Webber never actually played college basketball. Michigan had to vacate all of his accolades and all the wins the program accrued during his tenure after an investigation revealed that he accepted money from a booster while he was a student.

Here's where the opacity of the Hall of Fame's selection committee becomes particularly frustrating. Do voters care about the sanctity of the NCAA's draconian amateurism rules? Is that long-ago scandal the kind of thing they'd hold against Webber at a time when public opinion is beginning to recognize the exploitative nature of college sports?

Because beyond that, even acknowledging the warts and the injuries and the disappointments that plagued his career, it's hard to dispute Webber's Hall of Fame bona fides. If the Kings had won that West final over the Lakers in 2002 - a series that turned on a miraculous Robert Horry buzzer-beater in Game 4 and was later marred by a Game 6 officiating controversy - they would've almost certainly gone on to beat the Nets in The Finals, and Webber would almost certainly be in Springfield already. With very few exceptions, anyone who's ever been the best player on a championship team has gotten in.

Webber's case holds up without the ring, even if it isn't quite ironclad. How much longer will he have to wait before getting the call?

Joe Wolfond is a features writer for theScore.