'Practice dirty, play clean': How the aging Giants revamped their offense

A couple of months back, Andrew Cresci was watching a broadcast of a San Francisco Giants game when something caught his attention. The announcers from the opposing team brought up the unusual way the Giants were conducting batting practice at Oracle Park. Instead of a gray-haired coach lobbing balls at 40 mph or so at hitters, Giants batters were facing two pitches machines: one throwing at game-level velocity, the other spitting out darting breaking balls. The Giants were trying to make practice more game-like.

This is exactly what they were trying to accomplish with hitter training at Driveline Baseball, a private training facility where Cresci is a hitting instructor. At Driveline, coaches try to make the practice environment more challenging. After all, Cresci says, that's what happens in every other major sport in preparing for a game. For instance, in football, teams practice nearer game speeds and have scout teams simulate opponents. MLB? Not so much.

"For all its metrics, all of its scouting reports and the advanced data MLB has, you hear a lot of things about how the preparation hasn't really changed at all the last few years," Cresci told theScore. "Their preparation is the least game-like."

Cresci began playing detective. What were the Giants up to?

"I asked around before I started writing," Cresci told theScore.

Driveline clients and alumni include scores of players and coaches in affiliated baseball. Cresci reached out to as many as he could. He was fascinated by what the Giants hitters were doing collectively because their results were somewhat incongruous. After he cast out his net of inquiry, he shared some of what he learned on social media.

"SF is currently the only team hitting pregame on-field (with) pitching machines simulating pitch profiles of potential pitchers they are going to face," Cresci wrote in a Twitter thread in August. "Actively challenging hitters in the most game-like environment possible to prepare their hitters for success … crazy idea, right?"

For the longest time in baseball that was crazy, or at least rarely seen on a field.

Cresci believed the Giants' rethinking of batting practice played a role - possibly a significant one - in the Giants' remarkable season, a campaign in which they shocked baseball by winning an MLB-best 107 games and the NL West. Should the rest of baseball be rethinking its pregame rituals? The Giants might be ending BP as we know it.

Batting practice is generally uniform in its execution on major-league fields. Hours before first pitch, in any city, there are familiar sights and rhythms. A turtle-shell cage, the one that covers the home-plate area, is wheeled in by the grounds crew. A throwing platform is put in place some 45 feet in front of home plate, protected by an L-screen to shield the BP pitcher, who tosses offerings designed to be struck squarely. The results are shagged by teammates in the outfield, or become souvenirs to the early arrivers in the bleachers.

In this environment, hitters practice against nothing like what they'll see when the game begins.

"You are training in an environment that is not game-like at all," Cresci said. "Then you are going to a game that is exponentially harder than practice, and then you are doing that like once every 30 minutes between (at-bats)."

Have the Giants benefited from changes in hitting training at the major-league level? They've certainly benefited from something, because the Giants' run-scoring renaissance is remarkable on a number of fronts.

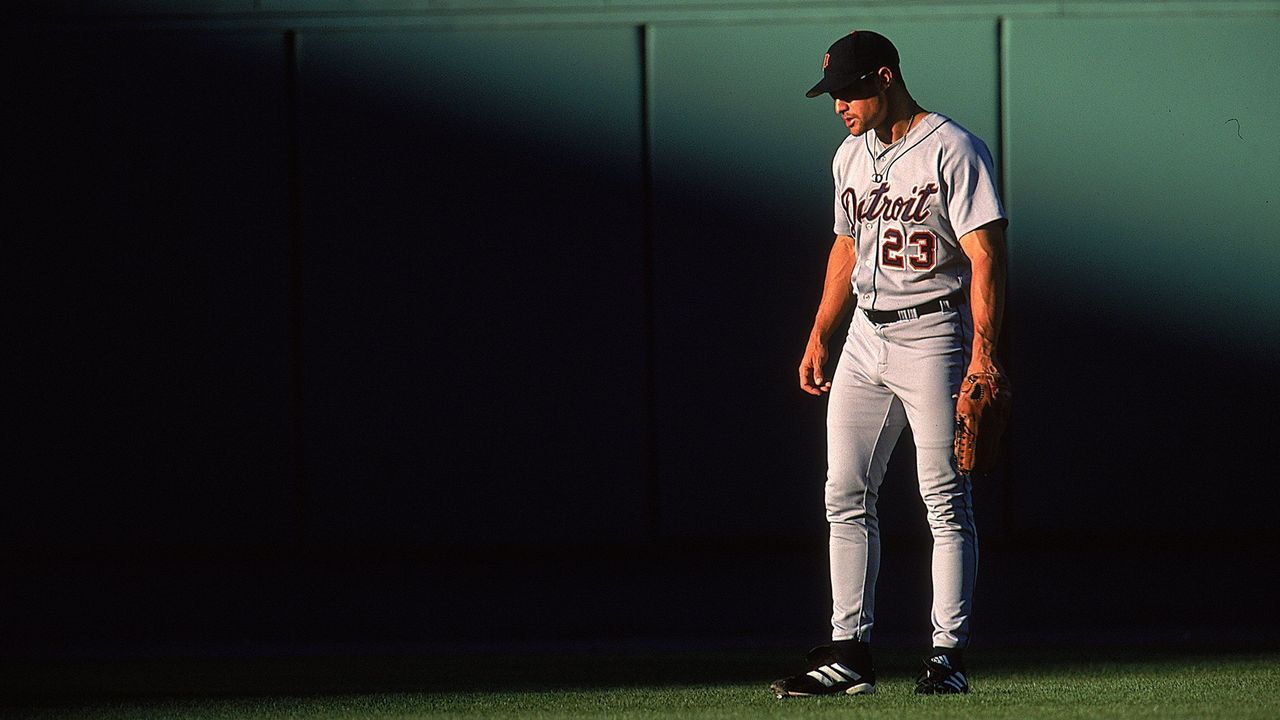

For starters, they field the oldest collection of hitters this season (30.6 years) at a time when the game is trending younger. That's more than two years older than the MLB average (28.4 years).

San Francisco's an ancient team by MLB standards, with a tremendous amount of roster carryover - of the 13 Giants who logged at least 250 plate appearances this season, 10 were with the club in 2019. The fact that they're the most improved hitting team, compared to MLB's last full season in 2019, is extraordinary.

From 2016-19, the Giants were a below-average offensive team every season. Their combined wRC+ during that span ranked 29th out of 30 teams, ahead of only the San Diego Padres.

In 2019, the Giants posted a dismal 82 wRC+ - a metric that adjusts for ballpark and run environment - that ranked 28th in the majors. That's a fancy way of saying they were 18% below average MLB offensive production. It's no wonder they won only 77 games and finished 29 games behind the Dodgers.

This season?

The Giants ranked fourth (108 wRC+), 8% above the MLB average. It was the largest improvement between 2019 and 2021 in baseball, and with the same mid-30s run producers - Buster Posey, Evan Longoria, Brandon Belt, and Brandon Crawford - who appeared to be in the twilight of their careers two years earlier.

The underlying skill gains are dramatic, too.

In 2019, the Giants were the fifth-worst team in the majors at swinging at pitches out of the zone (33.7%). This season, the Giants tied for the second-lowest out-of-zone swing percentage (28.2%), trailing only the Dodgers.

The Giants also made the greatest improvement in terms of contact quality. San Francisco's barrel percentage has improved more than any team since 2019:

The Giants' Darin Ruf told The Washington Post he's benefited from new approaches to practice.

"Early on in my career, everyone is telling me, 'Stop swinging at a slider low and away.' I was like, 'Yeah, I'd love to, but' … Now if I train my eyes to look up and in against guys that might be trying to spin it down and away, it can help me a little bit to lay off."

Perhaps there's some luck involved, but there's been plenty of change, too. The Giants hired a new coaching staff after the 2019 season.

Play-by-play voice Dave Flemming has called Giants games since 2003. Like players, announcers arrive at the ballpark hours before first pitch to prepare. Flemming's undoubtedly watched a lot of batting practice. Before a game this spring, he noticed something he'd never seen before: Giants batters were taking on-field hacks at what looked to be game-velocity fastballs and nasty sliders. Fleming was "astonished" by the practice, as he explained in an interview with a San Francisco radio station.

After watching the unusual display, Flemming asked Giants hitting instructor Donnie Ecker, hired after the 2019 season, about it.

"'Practice dirty, play clean,'" Flemming said Ecker told him. "Practice to make mistakes. Challenge yourself, push yourself, make it hard, make it not fun. And then when the game comes around, you play clean, and it feels a lot easier."

Ecker, selected in the 22nd round in 2007 by the Texas Rangers, never reached the majors. As recently as 2014, he was coaching at Los Altos High in California. But his curiosity in motor learning and biomechanics accelerated his coaching career. He became one of the first hires under manager Gabe Kapler in December 2019 after working previously in the Angels and Reds organizations.

While Google and Twitter searches for video and stories of what the Giants are up to before games return scant evidence - and the Giants did not respond to multiple interview requests from theScore - Giants outfielder Mike Yastrzemski did credit pregame work for the exact pitch he hit a game-turning grand slam on in a wild comeback win over the Diamondbacks in June.

"That was kind of the exact swing that we worked on," Yastrzemski said. "I got a pitch that was middle-in and didn't try and do too much with it, didn't try and yank it."

Kolten Wong told theScore his brother Kean, who was with the Giants in 2020, said the Giants were focused on improving pregame preparation.

"They're big on the high-spin machines," Kolten Wong said. "Everyone on the team seems to be hitting really well, so you put that in the back of your head and wonder, 'How can I add that to my game?'"

There have long been high-velocity and breaking-ball pitching machines in the depths of major-league stadiums, but Cresci wasn't aware of them often making their way onto the field. Even if they did at times, he doubts it had been done in a systematic way.

"They're doing it on the field, which I think is most ideal," Cresci said, "because if you're going to replicate a game environment you want to make it as game-like as you possibly can."

In a 2013 blog post, Kapler recalled something he wasn't prepared for when he played for Japan's Yomiuri Giants in 2005: real simulated batting practice.

He recounted how he'd homered on a sinking fastball in a game that season, and how earlier that day he'd faced live batting practice on the field. The pitcher was throwing him sinkers to replicate that day's starting pitcher. He was shocked by how Japanese teams would have two hitters take batting practice at the same time - separated by protective netting - versus live throwing: twice the reps and twice the intensity.

"I owed my smidgen of success that day to a batting practice session that had me working on, of all things, sinkers." Kapler wrote. "Coaches lobbing humped balls to the plate from a distance of 40 feet - the prevailing convention in batting practice in the U.S. - is hardly a game simulation. Generally speaking, hitters get very little out of this exercise that they couldn’t accumulate on their own in the cage with a tee or short toss in a shorter period of time. In a 162-game season that approaches 200 if you include spring training and potential postseason games, we need to be as economical as possible with our precious minutes. We can’t afford to be wasting essential vitality on exercises without reward."

Kapler was among those questioning traditional practices when he went on to work with the Dodgers in player development and later as the manager of the Phillies.

He wasn't alone or first in questioning training practices.

In 1938, Chicago Cubs owner Philip Wrigley asked sports psychologist Coleman Griffith to observe practice in spring training and attempt to quantify how much of baseball practice was actually valuable. Griffith concluded in his report an average of 47.8 minutes per day was "effective for the playing of baseball." In other words, a lot of the time was being wasted.

In 2012, Oakland A's third baseman Eric Chavez called batting practice a "waste of time."

When he was with the Rays and Cubs, manager Joe Maddon often canceled on-field batting practice sessions, questioned their value, and even reenacted the Allen Iverson talking-about-practice rant.

So the Giants aren't the only team rethinking training and game preparation for hitters.

In 2019, the Blue Jays hired a pair of former professional pitchers to toss batting practice to better simulate game conditions. Blue Jays general manager Ross Atkins said the goal was to “to expose (the concept) to the major-league level."

Rowdy Tellez told theScore that when he was with the Blue Jays, he used the Spinball pitching machine "iPitch system," which randomized pitch types, mixing in fastballs and breaking balls, to better replicate game conditions.

"We experimented with it," said Tellez, who's now with the Brewers. He said he also did some machine work on the field in Toronto, "but not much."

Brewers hitting coach Andy Haines told theScore there's even video of Babe Ruth being challenged with live batting practice.

Haines' younger brother, Kyle, is the director of player development for the Giants. The older brother knows some of what the Giants are up to, including bringing the high-velocity Hack Attack pitching machine - it spits out 100-mph fastballs - onto the playing surface before games.

Haines and the Brewers - the No. 2 seed in the NL playoffs behind the Giants - are thinking differently about BP, too.

Haines brought more game-like practice to Milwaukee. The Brewers do most of their high-velocity and breaking-ball training indoors, Haines said. In the indoor cages, Haines said the Brewers will adjust the legs of the pitching machine to better replicate the release point of that day's starting pitcher.

While progress might appear to be slow, Haines said many changes have been made at the minor-league level. In 2016, when he was the Cubs' minor-league hitting coordinator, Haines implemented "chaos training" to make pregame work more competitive.

"Usually that (change) has to matriculate up. It's more difficult to implement at the major-league level," he said.

The Giants have also made some of the greatest season-over-season gains in minor-league hitting performance from 2019 to 2021. What they're pulling off might be organizationally wide in scope and effectiveness.

One rival MLB player development official said what impresses him about the Giants is the buy-in they've received from veteran players. Everyone has access to the same tools and data but not everyone executes or communicates well, he said.

Cresci agreed.

"You have guys like Bryce Harper that are very traditional in their preparation. They are not fans of non-traditional training environments," he said. "It's hard to tell a big-league guy to change everything he's been doing. I'm sure (coaches) get a lot of pushback."

Perhaps it helps that Ecker is younger than Longoria and only a few weeks older than Posey.

St. Louis hitting coordinator Russ Steinhorn worked with Kapler in Philadelphia before joining the Cardinals' organization. The Astros, then on the vanguard of new development practices, first plucked Steinhorn out of Delaware State. An Astros official had read a Sports Illustrated "Faces In The Crowd" item about how Steinhorn's college program was leading the NCAA in on-base percentage thanks to unusual training practices.

"Having a little bit of experience with Gabe, and the way he thinks and how thoughtful he is, it's not surprising," Steinhorn said. "They've done a remarkable job."

Steinhorn suspects we're going to see more of the practices in the majors that have been tested in the minors, and outside the pro game.

"I think it's at the point now, as an industry as a whole, where I think players expect it, and anticipate it, and are more open to it," Steinhorn said. "They are seeing how it's changing careers, and giving guys more opportunities."

So will traditional on-field BP be a thing of the past?

Haines says some hitters are still "adamant" that traditional on-field batting practice helps them.

Brewers shortstop Willy Adames told theScore that his routine includes hitting high velocity and spin in indoor cages but that he likes traditional batting practice for psychological benefits.

"I feel (BP) is to feel good," Adames said. "To get yourself some confidence before the game."

Haines believes there are benefits to intense practice, and to "deliberate" practice.

Behind the scenes, it's tough to know exactly what, if any, secret sauce the Giants might have. Yastrzemski told The Athletic in an interview he's used virtual reality to prepare for pitchers.

"It's as real as it can get without actually being there," Yastrzemski said. "It's incredible. (The VR system) has every single pitch that every pitcher throws."

The company Winmill claims to have developed the first "automated" machine that is capable of "replicating any pitch in real life," though Steinhorn doesn't believe such next-generation machines are in scalable production. The Ringer's Ben Lindbergh wrote about the quest for the perfect pitching machine earlier this year. Hitters might soon be able to close the gap with pitchers when it comes to training tools and technology. That would allow them to make better batting practice happen anywhere.

But the Giants' 2021 edge might be low tech: better communication and asking better questions of how they're spending their time. The ancient general and philosopher Sun Tzu wrote that every battle is won before it is fought, and perhaps the Giants are doing just that.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.