Full Count: Bubble system necessary for MLB's postseason

The possibility of playing the entire 2020 season in a bubble gained little traction when Major League Baseball first explored it in April, about a month after the pandemic sent the sports world into hiatus. The idea of all 30 teams setting up shop in Arizona, or even across three separate hub cities, contained a veritable laundry list of logistical problems that - along with the deluge of negative feedback from the players - quickly rendered it something of a non-starter.

Still, while (most) teams will end up playing out the regular season from their home cities, the eventual World Series champions may hoist the Commissioner's Trophy from the relative security of a neutral, hermetically sealed environment. Just over two weeks into a season that has already been upended by coronavirus-induced complications and cancellations, the league is reportedly having preliminary talks about playing the postseason in a bubble-type format, according to ESPN's Jeff Passan:

Because of MLB's expansion to 16 playoff teams, the league would need at least three hubs to complete its wild-card round before shrinking to a two-hub format for the division series. The league championship series and World Series could be held at one or two stadiums. Remaining in one metropolitan area would allow teams to avoid air travel and perhaps remain at a single hotel for the entire postseason, which is scheduled to begin Sept. 27.

While such a system may not have worked for the regular season, you don't have to be an epidemiologist to realize that a bubble isn't just advisable but imperative for the playoffs - assuming the season makes it to October. Not only is it safer for the players, but it's also the only way to ensure that the postseason doesn't devolve into the farce the regular season has been.

Opening Day wasn't even three weeks ago and the coronavirus has already wreaked irreparable havoc on the league's schedule and its competitive integrity, a hardly unsurprising result given the trajectory of the virus in the United States and the mobility (and travel requirements) of baseball's players. A dozen teams had their schedules altered following two team-wide COVID-19 outbreaks, and the possibility of every club playing an equal number of games in 2020 seems exceedingly low.

The St. Louis Cardinals haven't played a game since July 29 because of their outbreak, which impacted 10 of their players and another seven staff members. It's unclear if the games will be made up, and it's even more unclear whether a team with only, say, 45 games played, should be eligible for the postseason.

But while canceling games or forcing teams to play with decimated rosters may work in the regular season, the league can't just cancel the National League Championship Series because the coronavirus infiltrated one of the teams. A bubble system, as evinced by relatively seamless starts in both the NBA and NHL, would dramatically improve the league's chances of staging an uninterrupted, legitimate postseason.

While the two leagues took different approaches - the NBA has successfully localized its entire league within the Disney World compound in Orlando, while the NHL split its league into two separate, self-contained hubs - both have demonstrated how effectively a bubble system insulates against infection: the NHL hasn't produced a single positive COVID-19 test since starting up two weeks ago, nor has the NBA. Neither league has had to cancel any games, either.

MLB should follow their lead.

Blackmon flirts with .400

Thanks to his torrid start at the plate, Charlie Blackmon has a chance to usurp Ted Williams as the answer to the tired trivia question: Who was the last player to hit .400 in a season?

Blackmon, who led the National League with a .331 batting average in 2017, owns a preposterous .500/.527/.721 line through his first 17 games of 2020, and the four-time All-Star has somehow gone 34-for-60 (.567) since going hitless in the first two games of the season. Just how feasible is it, though, that Blackmon finishes the season hitting at least .400 while receiving the 186 plate appearances needed to qualify for the batting title? Well, let's do some quick-and-dirty math.

- The Rockies have 43 games left. Since becoming a full-time player in 2014, Blackmon has missed only about 6.2% of his team's games per year, on average. Assuming that rate holds up, Blackmon will play in 40 of his club's remaining games. And with Blackmon averaging about 4.4 plate appearances per contest, that means another 177 plate appearances.

- Only at-bats factor into batting average, though, so let's figure out how many at-bats he should get. Blackmon doesn't walk much, though he does get hit by a decent number of pitches. All told, Blackmon has recorded an official at-bat in about 90% of his plate appearances since 2014. Assuming that rate holds up, Blackmon will receive another 159 at-bats this year.

- Ultimately, then, Blackmon should get around 227 at-bats in 2020. To hit .400, Blackmon will need 91 hits. He already has 34. As such, he'll need to go 57-for-159 (.358) the rest of the way.

Obviously, that's a tall order, even for a good hitter who gets to play half his games in an extremely hitter-friendly environment, where Blackmon owns a career .307 average. It's at least within the realm of possibility, though. Just last year, Blackmon hit .385 across a 36-game stretch early in the season encompassing 161 at-bats. Fans may not regard a .400 batting average in a bizarro 60-game season with the same reverence they do Williams' unforgettable 1941 campaign, but it'd be outrageously fun to watch Blackmon try to hit that hallowed mark.

Stroman opts out

Teams have been exploiting baseball's service-time rules for eons now, operating in bad faith with impunity by deferring call ups for deserving prospects until after they've secured a seventh year of control over that player's services. It happened to Ronald Acuña Jr., and Kris Bryant before him, and Bryce Harper before him. It's such a ubiquitous maneuver at this point that top prospects now expect it: "I mean, I know it's going to happen," Nate Pearson, the Toronto Blue Jays' top pitching prospect, said during spring training. "It's just the way the game is."

Pearson was optioned to Toronto's alternate training site to begin the 2020 season, only to be promoted to the big-league club on July 29. Had he been called up one day earlier, he would've been eligible for free agency following the 2025 campaign. Now, Pearson won't hit free agency until after 2026.

As such, it was undeniably refreshing to see the tables turned this week when right-hander Marcus Stroman opted out of the remainder of the 2020 season, pulling off an exquisite take-the-service-time-and-run move that rings of poetic justice. Stroman came into the season needing only a few more days of service time to qualify for free agency this winter. Because of a torn calf muscle, he had yet to pitch for the New York Mets this year, but players still accrue service time on the injured list. On Monday, once he had logged enough days to be eligible for free agency, Stroman opted out, citing COVID-19 concerns within his family.

To be clear, I'm not suggesting those concerns aren't real and valid. Still, the timing of Stroman's decision indicates he knew exactly what he was doing. And just as teams have no compunction about manipulating a player's service time, Stroman shouldn't have any about his decision, either. Teams squeeze every advantage out of the collective bargaining agreement in the best interest of the team because baseball is a business. Well, Marcus Stroman is a business, too. Anyone inclined to chastise him for his decision need only look at how baseball collectively exploits its labor force to understand why this wasn't a fleecing so much as karmic retribution.

Tatis mashes taters

Not since 1953 has a 21-year-old led the majors in homers. That year, Eddie Mathews, a future Hall of Famer coming off an auspicious rookie campaign, clobbered 47 round-trippers for the Milwaukee Braves, propelling the franchise to its best season (92-62) since 1914. Nearly seven decades later, Fernando Tatis Jr. is following the same blueprint.

The long-suffering San Diego Padres - now 10 years removed from their last winning season - are off to an uncharacteristically solid start at 11-7, and it's largely thanks to Tatis Jr., the electrifying shortstop who enters play Wednesday hitting .333/.407/.750 with eight home runs, one off the major-league lead.

Tatis, who's quickly building a case as baseball's most exciting player, showed big-time pop as a rookie in 2019, bopping 22 dingers with a .590 slugging percentage in 84 games, but it now appears - if his early-season batted-ball metrics are to be trusted - that he could be one of the game's most prolific power hitters for years to come.

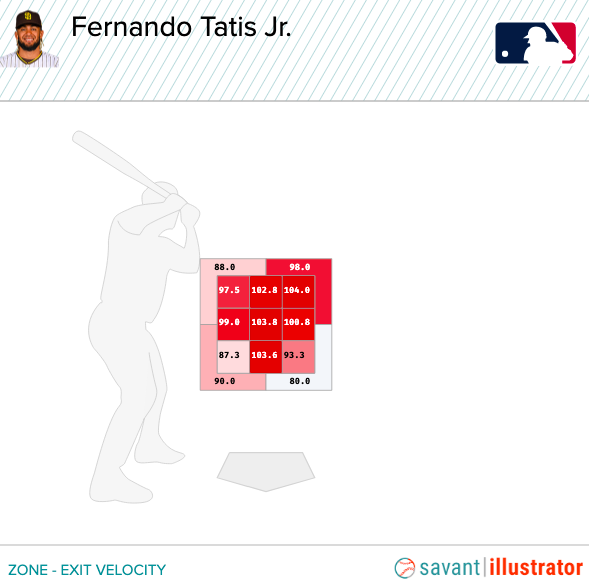

Small sample caveats apply, but Tatis leads all qualified hitters in average exit velocity at 97.1 miles per hour, and he's elevating the ball far more frequently than he did in 2019, raising his fly ball rate seven percentage points this year to 31.9%. Consequently, his barrel rate - the rate at which he produces a batted ball with an expected batting average of at least .500 and an expected slugging percentage of at least 1.500 - sits at 21.3%, fifth-best in the majors (min. 25 batted balls). Simply put, if you throw him anything in the zone right now, he's going to hit it hard and probably do damage.

Whether the youngster will be able to sustain this over the 60-game season and outslug Aaron Judge or Mike Trout remains to be seen, but the improvement Tatis has demonstrated through the early stages of 2020 is remarkable, and it bodes extremely well for a franchise that largely centered its rebuilding strategy around him.

Jonah Birenbaum is theScore's senior MLB writer. He steams a good ham. You can find him on Twitter @birenball.