Robot umps threaten the art of catching: 'You could throw it to a screen'

In November, the Texas Rangers signed Jeff Mathis to a two-year deal worth $6.25 million. Mathis, then months shy of his 36th birthday, hit .200/.272/.272 in 69 games with the Arizona Diamondbacks in 2018, underperforming teammate Zack Greinke - a pitcher - at the plate. Over his career, which now spans 15 seasons, Mathis has been historically punchless: Of the 1,845 players to receive at least 2,500 plate appearances since 1920, Mathis' lifetime .555 OPS is sixth worst.

Yet, even with teams increasingly loath to pay up for veterans, Mathis commanded a multi-year deal - with a higher average annual value than free-agent outfielder Adam Jones, a five-time All-Star - this past winter. Why? Because he can do this.

Is that pitch a strike? Maaaybe. It looked low, and possibly off the plate. Mathis' adroitness as a receiver, however, made it look like it was right at the knees and on the outside edge of the strike zone. He got the call. In 2018, Mathis converted 55 percent of borderline pitches into strikes, according to Baseball Savant's metrics (and definition of "borderline"), the best rate of any catcher in the majors. That's why he got paid.

Never before has the value of pitch framing - a catcher's ability to elicit strike calls with the way he presents borderlines pitches to the home plate umpire - been more widely understood and appreciated. It is increasingly viewed as an essential part of catching rather than as a niche skill subordinate to blocking, throwing, and hitting. In March, FanGraphs added pitch-framing data to its wins above replacement calculation for catchers. Baseball Savant boasts a robust catcher-framing leaderboard.

Yet, if MLB's experiments in the independent Atlantic League are a reliable portent of the future of the game, pitch framing may well be an art form with an expiration date.

Last month, in perhaps the most highly anticipated and potentially consequential Atlantic League trial to date, the league rolled out its automated strike zone - radar technology commonly referred to as TrackMan. Ball and strike calls are now largely out of the hands of umpires. (Umpires can still override the system at their discretion, if, for instance, TrackMan calls a strike on a ball that bounces in front of the plate but still ends up passing through the strike zone.)

The benefits, in theory, are clear: An automated strike zone eliminates inconsistency and human error, along with the game-delaying arguments and ejections that come with it.

The rationale is sound. This, for instance, shouldn't happen in a major-league game:

As my mom used to say, “I’m not mad, just very disappointed.”😱 https://t.co/kVQiql9QUt

— Tony Kemp (@tonykemp) August 14, 2019

On the flip side, though, an automated strike zone renders pitch framing effectively meaningless. Even the most gifted receiver can't fool a computer.

"It doesn't even really matter how you catch it," pitcher Daryl Thompson, a former big leaguer and the current ace of the Southern Maryland Blue Crabs, said when theScore visited the Atlantic League in July. "It's almost like you could throw it to a screen back there."

"Before, you had to catch the ball and give it a good frame," added Blue Crabs catcher Charlie Valerio, who spent a half-decade in the Cleveland Indians' farm system. "And now it doesn't matter. And the scout's looking (at) how you do behind home plate, how many (borderline) pitches you make for strikes, if your framing is good or not. Now they don't care how you catch the ball. If the ball hits the TrackMan, it's a strike. It doesn't matter how you catch the ball."

Atlantic League president Rick White believes the consistency of the automated strike zone will "more than (make) up for" the potential value lost for catchers with the elimination of pitch framing.

"I'm a former catcher, and I do believe in the art of presenting the ball to the umpire," he said. "However, I believe that what we're accomplishing with the standardized strike zone is far more important."

For catchers such as Mathis, it isn't. Mathis literally gets paid to exploit the umpire's fallibility - their humanity, if you will.

"I know a lot of catchers (love) the art form of catching, and their pride and joy is to make pitches that are close outside the zone look like strikes," said Blue Crabs outfielder Tony Thomas. "It eliminates that art form. And then I know a lot of guys get to the big leagues because they can receive well. The catching position wasn't a hitting position; it's a guy that can make pitches look like strikes and know how to call a game."

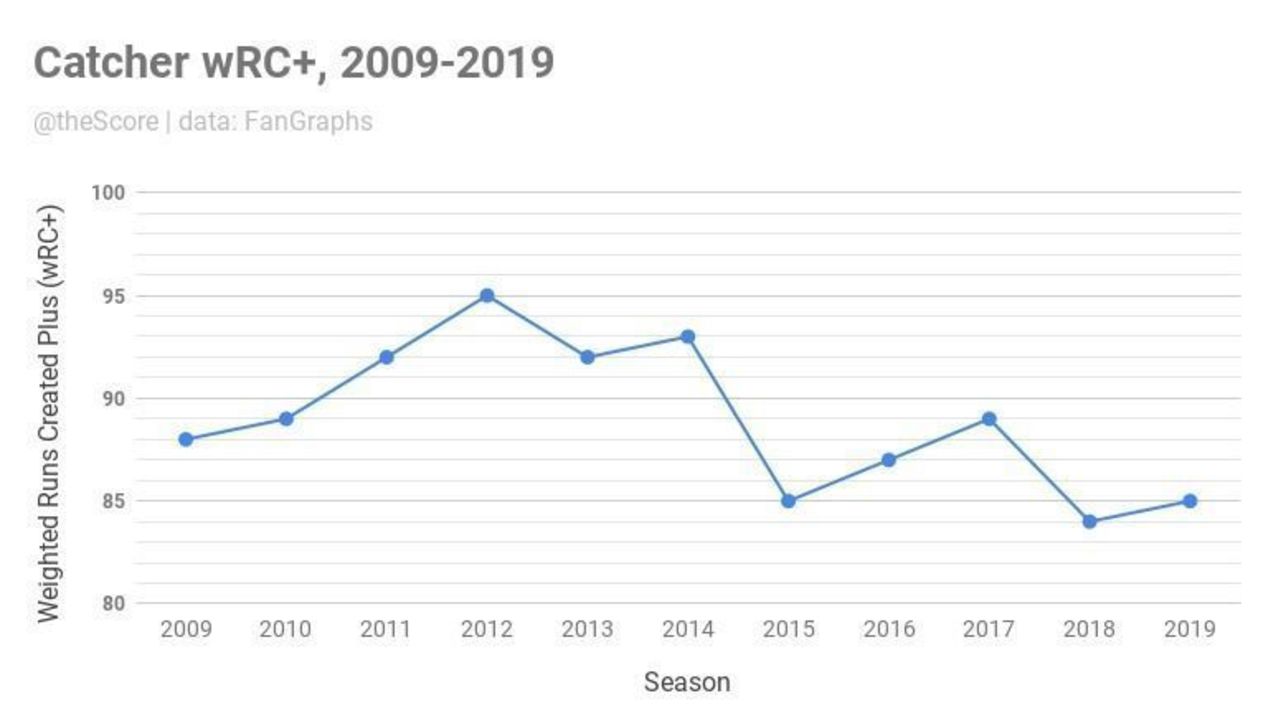

Implementing an automated strike zone, then, could redefine the position altogether. Theoretically, if pitch framing goes extinct - while the stolen base continues to fall out of fashion across the majors - teams could place a newfound emphasis on offense behind the plate, which would be a significant departure from how the league currently views the catcher position. Last year, catchers were worse at the plate (84 wRC+) than they had been in more than a decade:

Ultimately, though, switching to an automated strike zone seems increasingly inevitable in MLB. Commissioner Rob Manfred, who was once opposed to the idea, has since softened his stance. He noted in July that player support is robust. It's hardly imminent, but the system's relatively auspicious start in the Atlantic League suggests robot umps are the way of the future.

That future likely won't have a place for Jeff Mathis and his ilk.

Jonah Birenbaum is theScore's senior MLB writer. He steams a good ham. You can find him on Twitter @birenball.