Cult Heroes and Club Icons: The Three Degrees and the rise of the black footballer

theScore's "Cult Heroes and Club Icons" is a weekly feature that examines compelling and engaging stories in the annals of world football.

The history of sport is littered with names of those bestowed with the honour of "being first," but that often overlooks those with more significant barrier-breaking influence.

Laurie Cunningham was not the first black player to pull on an England kit - though he was considered such at the time - and West Bromwich Albion was not the first British side to field three black players at once when they did so in 1978 with great regularity.

Those distinctions belong to little-known schoolboy Benjamin Odeje and a West Ham side in 1972 that featured the trio of Clyde Best, Ade Coker, and Clive Charles.

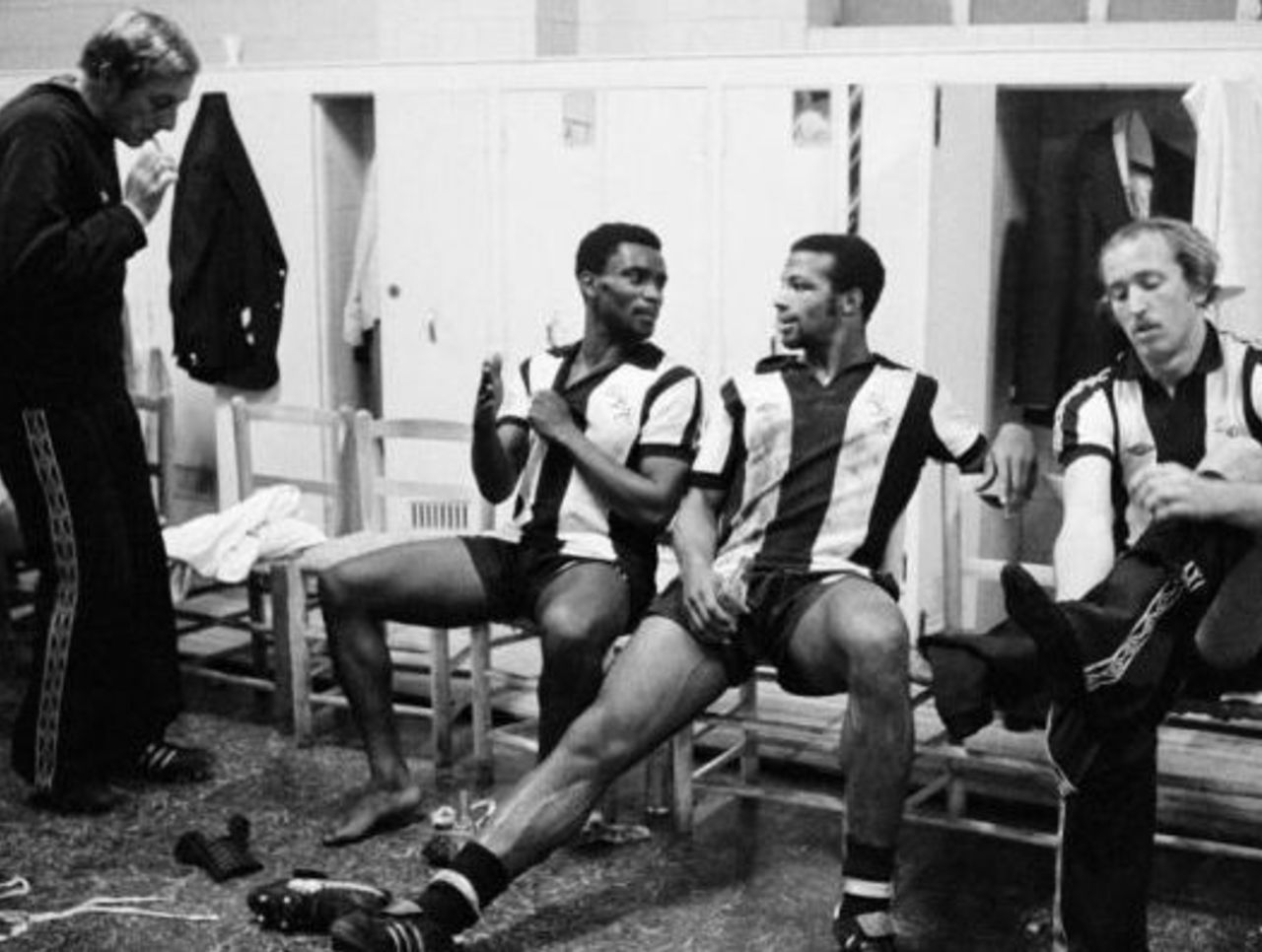

Six years later, though, Cunningham on the wing for the Baggies, blessed with pace and panache, alongside right-back Brendon Batson and thunder-footed striker Cyrille Regis, formed the Three Degrees.

The nickname, conceived by then-boss Ron Atkinson in 1978, was a nod to contemporary American female R&B trio The Three Degrees, who were more popular on U.K. charts than they were stateside.

An era fraught with discord

Before Tony Pulis mastered ennui with his brand of "avoid relegation at all costs" football, and before former Baggies midfielder and Three Degrees teammate Bryan Robson bossed the side to a final-day great escape, West Bromwich Albion set the English football world afire by starting three black players.

Peering over a wall at the glitz and glamour of England's marquee sides, an oft-overlooked club kicking off ten years of top-tier football in the West Midlands broke barriers when the country was riddled with divisive and destructive racial tension.

The National Front, a far-right political party exclusively for whites, fielded 303 candidates during the 1979 general election, collecting 191,000 votes. Opposed to non-white immigration and in support of repatriation, the National Front's insipid peak was at its height when the trio of Baston, Cunningham, and Regis began to take the league by storm.

Targeting disenchanted spectators filling football terraces countrywide, the National Front attempted to spread its hate among supporters who no longer felt the sense of entitlement they had prior to Margaret Thatcher's reign of privatisation amid post-colonial rule.

With three black players thriving for the Baggies, the club became a target for extremists, magnifying the typical derision from rival supporters with bigoted whistles and intolerant remarks directed at the trio.

"At the beginning of the game, the three West Brom players got fruit thrown at them. Each time one of them touched the ball, the booing was horrendous," Lord Herman Ouseley, current chairman of English football's anti-racism group Kick It Out, said of a match at Stamford Bridge.

"After about 20 minutes, Laurie weaved his way through the Chelsea defence and Cyrille banged the ball into the net. The guys sitting around me were enraged. They stood up and the abuse reached a cacophony."

Brendan Batson

Batson garnered the fewest accolades of the trio, though his impact cannot be undersold. Blessed with a cocktail of speed and positional awareness, Batson engineered many attacks while overlapping with Cunningham on the right flank to great results.

An Arsenal academy graduate, Batson was the first black player to suit up in the Gunners' first-team red strip before moving to Cambridge United in 1974, where he was bossed by Atkinson.

When Atkinson made the Hawthorns switch in 1978, he brought more than his larger-than-life personality; he brought with him a fullback primed for top-tier football.

Batson joined Regis and Cunningham a year after their Hawthorns pilgrimage, and the three combined for 120 appearances in all competitions alongside a core of Tony and Ally Brown and Robson in 1978-79. West Brom finished third in the league that season and bowed out of the UEFA Cup in the quarterfinals to Red Star Belgrade, both club bests.

When defences began to narrow the pitch to limit Regis' movements on the edge of the 18-yard box, Batson would maraud down the flank, spraying incisive crosses to the dismay of defenders.

Batson ended his career at West Brom in 1982 stricken by serious injury, then took a gig with the Professional Footballers' Association as an administrator.

Cyrille Regis

From non-league football to West Bromwich Albion thanks to Baggies scout-cum-manager Ronnie Allen, Regis moved to the top flight in May 1977 from semi-pro side Hayes for a meagre fee of £5,000, plus another £5,000 after 20 appearances.

Regis almost instantly became a fan favourite, scoring twice in his first team debut - a 4-0 drubbing of Rotherham in the League Cup - before scoring on his league debut three days later against Middlesbrough. The French Guiana-born striker capped off a meteoric rise by scoring in his first FA Cup match against Blackpool the same season.

Like Cunningham, who was only capped six times by England’s senior squad, the five-time capped Regis struggled for appearances for the country despite his performance in the nation's top flight. He still enjoyed a decade-and-a-half stretch from 1977-91 with West Brom and later Coventry City.

In the same way Cunningham's pace and dribbling marked the emergence of a new breed of footballer, Regis' power was similarly unplayable on its day.

Honoured as a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in 2008, Regis is widely considered one of West Brom's best players ever, and the early prototype of the energetic and robust striker.

The seeds of change begin to bear fruit

An epic 5-3 thumping of Manchester United during the 1978-79 campaign highlighted both the good and the bad of football at the time.

Cunningham and Batson combined on the right flank to absolutely savage a talented United side, while Regis used his strength to carve the backline to fragments.

Pockets of United supporters whistled the trio (as did many fans on the cusp of the 1980s), while some shouted hate-laced obscenities that can be heard during the broadcast.

By this time, however, the script was beginning to change courtesy of the Three Degrees and their contemporaries. Black footballers were gradually becoming not only prominent, but celebrated.

While Regis won the FA's Young Player of the Year award that season, it could have just as easily been given to Cunningham.

The Three Degrees represented more than just a shift for black footballers; they were a viable threat characterized by fluid, attacking football that both thrived on the wings and benefited from Regis' central dynamicism.

Laurie Cunningham

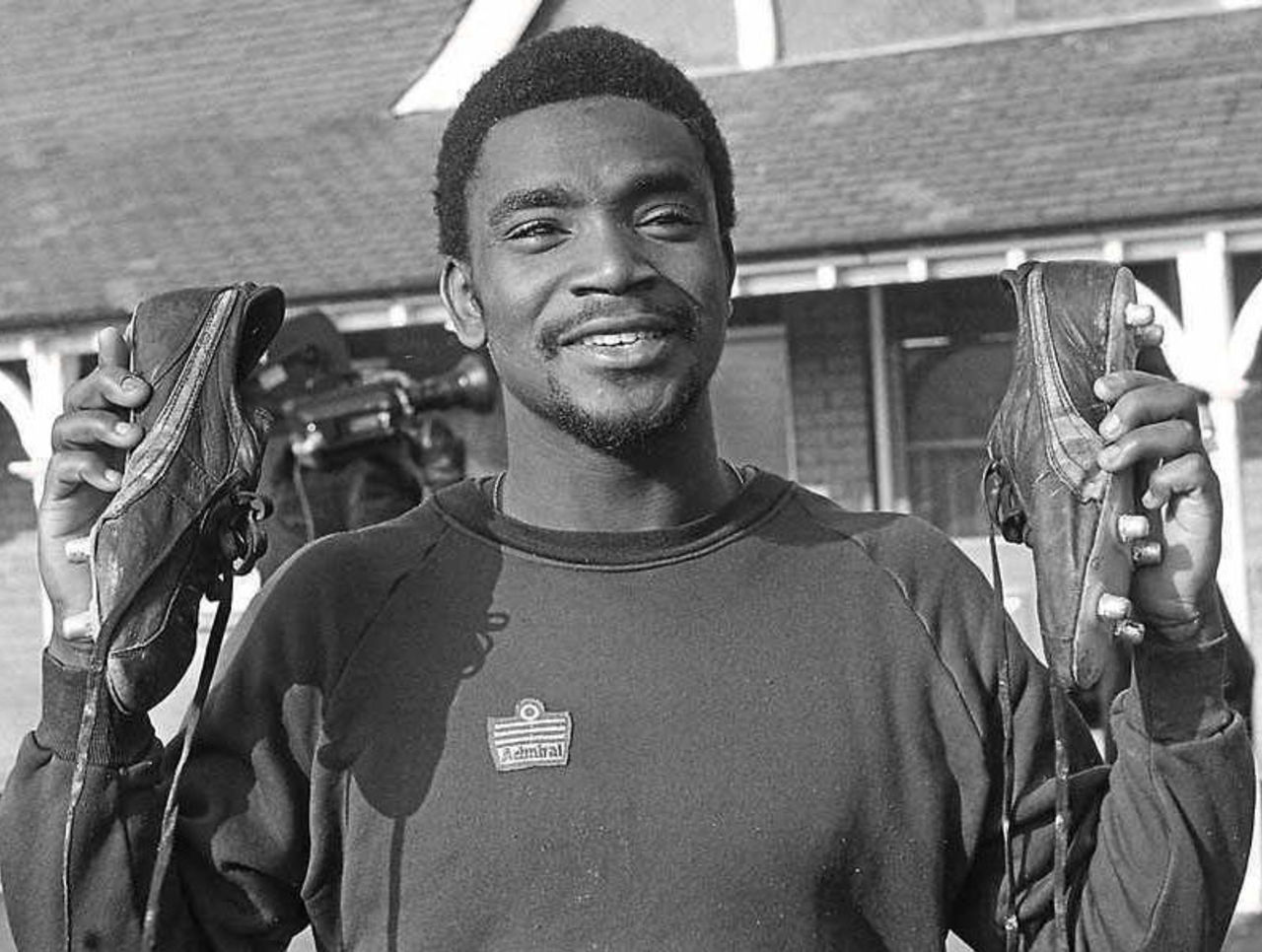

When Laurie Cunningham was first capped by the England under-21 side on the heels of his meteoric rise from ballet neophyte to Leyton Orient to West Brom, football supporters witnessed a change in the social and demographic foundations of domestic association football.

Cunningham was utterly liquid in attack, like a surge of potent waters shattering a tattered levy.

Nightmare fuel for full-backs, he used his renowned dancing skills and sense of balance to dribble through defenders in a time when crunching tackles were the norm and yellow cards were reserved for violent conduct that today would be a straightforward red.

On the success of a sixth-place Division 1 finish in 1977-78, West Brom made it to the quarterfinals of the UEFA Cup the following year, including a victory over Mario Kempes and Valencia where Cunningham's star shone its brightest.

The footballing world took notice.

Real Madrid came for Cunningham in at the end of that season, and as Atkinson would later say, "You don't turn Real Madrid down."

Cunningham's £950,000 move to the Spanish capital wasn't in the mold of later moves by British talents like David Beckham and Gareth Bale. This was a time when the Madrid giants looked within for talent, not across borders - Cunningham was the first British player to move to the Santiago Bernabeu.

"The club made a big effort financially to sign Laurie … to sign a star, because most of us were from the youth team," current Spain coach and Cunningham's former Los Blancos teammate Vicente del Bosque said in the ITV documentary "The Laurie Cunningham Story."

At Madrid, Cunningham scored a brace on his debut and won both the league and the Copa del Rey. Injuries began to hamper both his progress and a regular spot in the England squad, though, and he made sporadic appearances for Real in the 1982-83 season, prompting a return home to play for Atkinson at Manchester United on loan.

Spells with Sporting Gijon and Marseille were followed by another injury-riddled campaign at Leicester City that led to a move to Belgium before a short-term stay with Wimbledon.

His time with the Dons was notable for his role in the club's famous 1-0 1988 FA Cup defeat of Liverpool before he returned again to Spain to help Rayo Vallecano's successful promotional 1988-89 campaign.

On July 15, 1989, at age 33, Cunningham died in an auto accident in Madrid. Two years earlier, both Cunningham and Regis walked away from a similar crash.

Like fellow barrier-smasher and Norwich City legend Justin Fashanu, Cunningham was a trendsetter whose death marked a career unfulfilled.

Three degrees of influence

For each banana thrown at Cunningham, or each ball bearing whipped in Regis' direction amid choruses of drowning whistles, teenage English players like John Barnes, Les Ferdinand, and Paul Ince were enabled by the West Brom trio.

After them came Ashley Cole and Rio Ferdinand, then the comparatively halcyon days of Daniel Sturridge, Raheem Sterling, and Danny Welbeck. Their tenures as Premier League pros were paved by Cunningham, Regis, and Batson, who confronted the obstacles that faced them with equal parts aplomb and composure.

Racism is football's plague, but its diminished reach in the English game is owed to players like the Three Degrees, who were as brilliant on the pitch as they were at catalysing change.