Tricky Dick and baseball's backwards drug culture

In the summer of 1973, the United States Senate Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency held investigative hearings "on the proper and improper use of drugs by athletes."It was one of the governments first major actions on the issue of drugs like amphetamines, anabolic steroids and others in sports. The following comes from the testimony of Jack Scott, founder of the Institute for the Study of Sport and Society, who was once called an enemy of sport, a "permacritic" and a "guru from Berkeley" by Richard Nixon's Vice President, Spiro Agnew. Scott assessed a major drug problem in sport, particularly regarding the use of amphetamines and anabolic steroids, and he believed America's major sporting organizations were engaged in a cover-up, that their drug education programs were nothing but public relations campaigns to protect the league from scandal.

[COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN] SENATOR [BIRCH] BAYH: If indeed the assessment of drug problems generally and of anabolic steroids and amphetamines by athletes are both true; it seems to me that you are not making a realistic appraisal if all of these things are in fact going on.

I don't think we can say it is insignificant to have star athletes telling kids in the streets that they are not going to make it to the Super Bowl if they use these drugs, so they better not use LSD, heroin or marijuana.

MR. SCOTT: I didn't say that it was insignificant, I called it a coverup of the problems of drug abuse that exist in athletics. The NCAA and NFL in 1970 and 1971 when there was a tremendous output of books and articles (Ed. note: see last week's column for an example) and other information revealing the extensive use of the drugs in athletics, it was in 1970 and 1971 when these commercials began appearing on television and the commercials quite inconspicuously did not deal with drug usage in athletics. Now, I would like to say, here for example, is a book that is put out by the office of the Commissioner of Baseball. The "Baseball vs. Drugs," and this is an education [and] prevention program. There is not one mention of anabolic steroids in the entire booklet -- one of the chief drugs athletes are using to help their performance. If you would like to look through the book or members of the committee, you will find extensive talk in here about opium, the opium poppy, codeine, heroine, morphine, marijuana, methadone, things like that which for people like myself who have to work in the world of athletics and are concerned with these problems, this kind of literature is not directed at us to give us information so we can deal in constructive fashion to combat drug abuses in athletic sports. It seems, as Professor [John] Kaplan from the law school at Stanford University has pointed out, in the following comment:

"Any drug program using athletes is bound to be a failure, first of all, it is using hypocrites because athletes pop the pills like anybody else. Secondly, they have no expertise. They don't know what they are talking about and they only heighten the interest of young people in drugs. I think sports are patting themselves on the back. They're probably trying to combat the publicity about athletes using drugs."

Fast forward 42 years, and Scott and Kaplan's words prove prophetic. The sporting press and the government largely ignored the steroid issue until Congress finally threatened action against Major League Baseball in 2004 if it did not enact a steroid testing program. There was digging and occasional articles which threatened to blow the lid off the story, but it took the threat to the record books posed by baseball's steroid era to finally force public outrage over steroid use. And even then, the rage was not directed towards teams for their blatant disregard for player health, but rather over a supposed danger posed to the "integrity of the game."

This is the cover of the 1970 Major League Baseball "Baseball vs. Drugs" book Scott referred to, from Appendix 28 of the hearing records.

In a message accompanying the book, commissioner Bowie Kuhn outlined the program's elements (also from Appendix 28). It includes:

A highly important aspect of the program is the participation of each club in community action drug-abuse programs and all ballplayers are encouraged to take part in such programs, as a number of ballplayers have been doing for some time. The success these players have had prove that this phase of our program can make a substantial contribution toward the national effort infighting drug abuse among our youth.

I am also requiring that the clubs report to my office all instances of illegal drug use or involvement. Baseball must insist that its personnel live within the federal and state drug laws. Discipline will be considered in cases of illegal involvement in drugs. It is not possible to set forth hard and fast rules regarding discipline. This subject will be considered on a case-by-case basis as we go along.

We have had no serious drug-abuse problems in Baseball and the objectives of our program are to keep Baseball free from any drug problem and thus protect the enviable record that we have, to protect the honesty and integrity of our game, and to protect the health and safety of our players.

Nowhere are amphetamines, steroids or any other drugs specifically mentioned. And it should be noted that Kuhn lists protecting baseball's "enviable record" as a priority before the health and safety of his players. But it was enough for those concerned in the US Government.

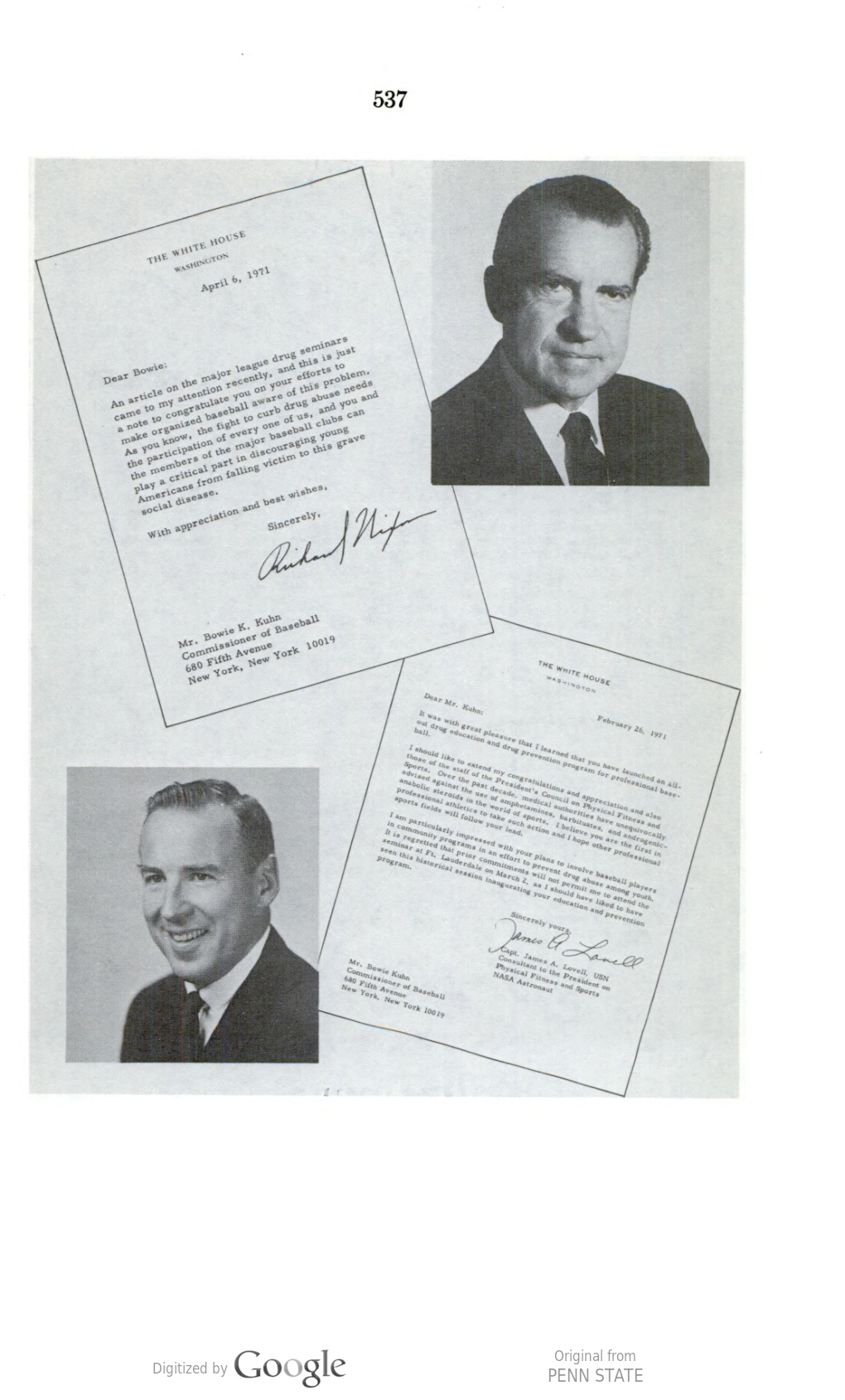

On April 6, 1971, less than a year after Major League Baseball published its anti-drug handbook, President Richard Nixon wrote Kuhn to "congratulate you on your efforts to make organized baseball aware of this problem. As you know, the fight to curb drug abuse needs the participation of every one of us, and you and the members of the major baseball clubs can play a critical part in discouraging young Americans from falling victim to this grave social disease." Navy Captain James A. Lovell, Nixon's "Consultant to the President on Physical Fitness and Sports" and a former astronaut, echoed the President's remarks and added he was "particularly impressed with your plans to involve baseball players in community programs in an effort to prevent drug abuse among youth" (again from Appendix 28).

The insistence of Kuhn that baseball was free and clear of a drug problem is impossible to justify, as multiple books such as Jim Bouton's Ball Four and Jim Brosman's Pennant Race had detailed the widespread use of amphetamines and other drugs among baseball players within the previous 15 years. Brosman was excerpted in a 1969 Sports Illustrated article on the rise of drug use in sport that was included as evidence in the hearing:

"Where's the Dexamyl (a combination barbituate and amphetamine), Doc" I yelled at the trainer rooting about in his leather valise... "There's nothing here but phenobarbital and that kind of stuff."

"I don't have any more," said Doc Rohde. "Gave out the last one yesterday. Get more when we get home."

"Been a rough road trip, huh, doc? How'm I goin' to get through the day then? Order some more, Doc. It looks like a long season."

"Try one of these," he said.

"Geez, that's got opium in it. Whaddya think I am, an addict or something?"

With the help of a willing baseball press, those who spoke out where successfully labeled as crackpots or the like by baseball's powers that be. That apparently extended to Nixon and his advisors, who felt Kuhn's unsubstantial education program was not just enough but worthy of congratulations. Scott was suspicious. His testimony continued:

MR. SCOTT: Interestingly, about 1 year ago, representative Rogers from Florida was going to hold hearings which were going to inquire into drug abuse in athletics. At that time, Mr. Rogers aide informed me that the day the hearings were to begin they received a call from the White House requesting that the hearings be postponed because on that very same day that Mr. Rogers was supposed to begin conducting hearings into drug abuse in athletics, President nixon was inviting the athletes who participated in these anti-drug commercials on TV to the White House to compliment them for their efforts in combating drug abuse.

SENATOR BAYH: I am not at all familiar with that, but I do know Congressman Rogers. I do know that he has been one of the most severe critics of the administration particularly in the area of health programs. It is hard for me to bleieve that he has been intimidated or persuaded not to hold hearings by a call from the White House. If you had seen him rake Eliot Richardson and other administration officials over the coals as I did, that would be a pretty hard one to buy.

MR. SCOTT: The hearings have not been held. They were supposed to be held and perhaps he does not feel the matter is very significant. It is also worth noting that Mr. Nixon's call to Mr. Rogers was pre-Watergate.

SENATOR BAYH: I don't know why the hearings haven't been held. A claim that a call from the White House could intimidate that man is inconsistent with what I know about that man.

MR. SCOTT: His assistant didn't claim that he was being intimidated, of course, he just felt that he was being considerate. The President was inviting athletes to the White House who participated in the anti-drug program and they just asked as a kindness if perhaps the hearing could be delayed for a short period of time. Whatever the reason, the hearings that were scheduled have not been held to date.

The idea that Richard Nixon was involved in shady dealings is not one that should require an abundance of convincing. But, it still seems like a motive is necessary. For that, turn to former Major League Baseball Players Association Executive Director Marvin Miller, who wrote about his dealings with Nixon in his autobiography, A Whole Different Ball Game.

In 1966, when Miller was tabbed for the job, he needed to pick a general counsel for the Players Association. Robin Roberts, the Hall of Fame pitcher who suggested Miller as executive director, called with a suggestion:

"Have you picked your general counsel yet?" Roberts asked hesitantly.

"No," I said, though I planned to offer the job to Dick Moss as soon as our funding was in place.

"Well, try this suggestion on for size. Richard Nixon is still interested in the job. I know you're not a big fan of his," Roberts said, "but he's in New York. Will you at least go talk to him as a favor to me?"

[...]

Drinks in hand, Nixon, his associated, and I amiably rambled on about the 1966 season. Thirty minutes passed. I didn't want to discuss politics, and I ccertainly was not going to bring up the matter of the next general counsel of the Players Association. Just before I was set to leave, Nixon's expression turned serious, or rather more serious. Here it comes, I thought. "Mr. Miller," he said, "you have a very difficult job in front of you. Let me know if I can do anything to help you. I am on very good terms with the owners." I thought to myself, "Yes, I bet you are."

Nixon, of course, did not become general counsel to the Players Association, but he did remain on good terms with baseball's owners. And it hardly seems like a stretch for Nixon to offer Kuhn and his friends in baseball ownership a hand with the public relations stemming from the impending drug problem in sports. If so, it would fit right in to the history of decades of drug use in baseball, under the noses of an impotent baseball press and a government only superficially interested in curbing such activities and protecting the health of its athletes.

Somehow, blame for drug use in sports continues to fall on athletes first and all other parties -- from leagues to team doctors to government bodies -- last. And when sports leagues leap into action, it is only to enact disciplinary codes on its athletes, with zero focus on the suppliers of these drugs or the health of the athletes who feel forced to take drugs to compete. These campaigns continue to be naked public relations in the same vein as Commissioner Kuhn's educational booklet. Until the health of the athlete is put first and foremost and public relations are tossed aside, there will be no progress on the drug issue. But when those in charge can simply say they are fixing the problem, congratulate themselves and move on, there is no reason to believe we will get anywhere constructive any time soon.