Roger Goodell hopes you've forgotten the recent past

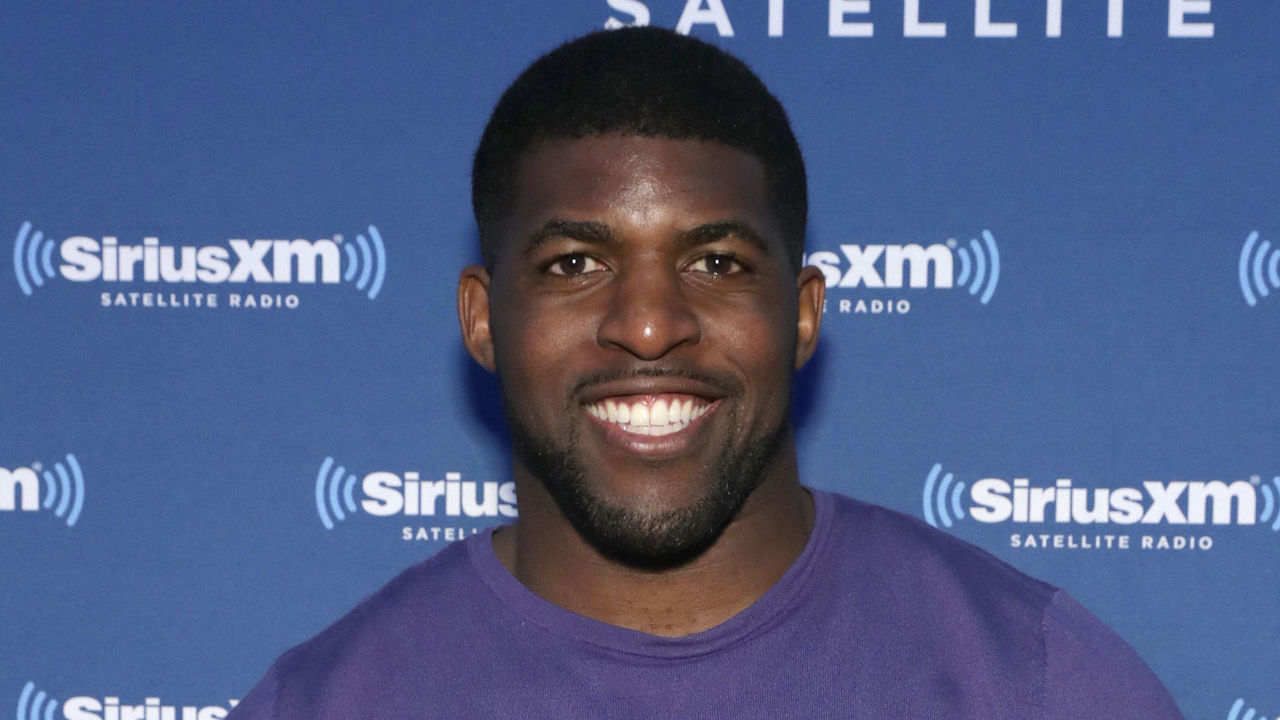

Let's start by giving credit where it's due: Ex-NFL linebacker Emmanuel Acho's two-part interview with league commissioner Roger Goodell, the latest installment in Acho's "Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man" series, had every good intention.

Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man: The National Anthem Protest- PT. 1

— Emmanuel Acho (@EmmanuelAcho) August 23, 2020

NFL Commissioner, Roger Goodell, & I discuss Colin Kaepernick & the protests during the national anthem that polarized America. pic.twitter.com/PcL02732ys

Uncomfortable Conversations with a Black Man: The National Anthem Protest- PT. II

— Emmanuel Acho (@EmmanuelAcho) August 24, 2020

In Part II: Commissioner of the NFL, Roger Goodell, answers whether or not players should be punished for kneeling during the National Anthem. Watch & SHARE. Love y’all ❤️. pic.twitter.com/UAziPYE3D3

The aim was to foster a dialogue; to present an opportunity for a rich white man in a position of power and influence to publicly explain what he's discovered about the Black experience. The result was largely an infomercial for the NFL, a multibillion-dollar corporation that only now realizes it's safe to attach itself to causes like Black Lives Matter because of the branding possibilities it presents.

That the interview was so effective as propaganda - NBC's Peter King called Goodell's admission that he wished he'd listened to Colin Kaepernick sooner "the quote of the year" - speaks to how easy it was for Goodell to successfully reframe the issue of racial injustice on the NFL's terms. Watching the interview without considering the context of the events of the last four years, one might come away thinking Goodell and the league had been passive actors, rather than active participants, in fostering the sort of negative perceptions Goodell now decries.

The interview opened with Goodell describing how his father, a Republican senator from New York from 1968-71, went from supporting the Vietnam War to opposing it after meeting with college students. Goodell said his father changed his position knowing that it might torpedo his re-election chances, and it ultimately did.

"It's not always easy to know what's right, but you have to have the courage to do it," Roger Goodell said. This is indeed a noble sentiment, but it's hard to square with his recent shift of support to BLM and the likelihood of player protests. He and the league have nothing to risk at this point.

"I'm a big believer in dialogue, and you really don't learn until you’re uncomfortable," Goodell told Acho. "I'm very comfortable talking about race. I have all my life."

Goodell and the league were actually uncomfortable in 2017, after President Donald Trump referred to any player who might kneel during the anthem to protest racial injustice - a practice Kaepernick had begun a year earlier, at the expense of his job - as a "son of a bitch" who needed to be taken "off the field." This prompted a wave of protests during pregame anthems across the league, which led to a tense meeting between players and team owners in New York City a few weeks later.

After that meeting, Goodell spoke to the press and made four references to "the dialogue" that had taken place. "Listening to our players and understanding our players, trying to address those underlying issues, and making our communities better is where the real opportunity is," Goodell said that afternoon. "There is a great deal of support for the efforts that our players have identified. They (the owners) not only support but recognize that these are important issues for our communities." Goodell never once used the words "race," "racism," or "police brutality." It must have made him uncomfortable.

When Acho asked Goodell what he knows now that he wished he knew then, Goodell replied, "Just what was going on in the communities." Never mind that the self-described "big believer in dialogue" was proud to tell you he had been listening at the time.

Acho allowed Goodell to avoid apologizing to Kaepernick by instead asking what he'd say if he were to apologize to him.

"The first thing I would say is I wish we had listened earlier, Kap, to what you were kneeling about and what you were trying to bring attention to," Goodell answered. "We had invited him in several times to have the conversation, to have the dialogue. I wish we had the benefit of that; we never did. We would have benefited from that, absolutely."

So: Goodell acknowledged that he wished he had listened, even as he shifted the burden back to Kaepernick for not coming in to meet with him at a time when the league's posture toward protesting players was outwardly hostile. This is where I should add that Kaepernick wasn't invited to that owners-players summit in October 2017.

Goodell also emphasized to Acho that the league never punished a protesting player, which ignores what ultimately happened to Kaepernick's playing career as well as the threats of retribution made by owners like Jerry Jones. This is how the NFL does dialogue.

Goodell really got into laundering his and the league's image when Acho asked him what he'd say to people who still think the protests are about the flag or the anthem.

"It's not about the flag," Goodell said. "The message here, what our players are doing, is being mischaracterized. These are not people who are unpatriotic, they're not disloyal, they’re not against our military. In fact, many of those guys were in the military, and they’re a military family. What they were trying to do was exercise their right to bring attention to something that needs to get fixed. That misrepresentation of who they were and what they were doing was a thing that really gnawed at me."

Yet after that 2017 league meeting, this is what Goodell had to say: "Another issue we spent a great deal of time talking about this morning was how much we believe that everyone should stand for the national anthem. That is an important part of our policy. It's also an important part of our game that we all take great pride in. It is also important for us to honor the flag and our country - our fans expect us to do that."

Roger Goodell's misrepresentation of who the players are and what they were doing must really gnaw at Roger Goodell. In May 2018, the league's owners approved a policy that was designed to keep players from protesting, without having consulted the players. The NFLPA filed a grievance, players promised to make a big stink about it, and, in short order, the league backed down by quietly not bothering to enforce the policy. Sports Illustrated's Albert Breer reported that the league and the NFLPA had data indicating that Trump's attempts to gin up outrage at the protesters wouldn't have a lasting effect. It's hard not to think Goodell's about-face in support of the players was similarly motivated by a focus group. This is how the NFL does courage.

There's more of this in the interview, of course, and you can watch it all for yourself. Goodell did admit the video he made in June to express support for Black Lives Matter was his personal response to a video made by a group of players, without the consultation of any owners, because: "It's who I am and what I believe in." He made no reference to the empty statement the league issued on his behalf days earlier about the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and the murder of Ahmaud Arbery. But his position now? That's who he is and what he believes in.

Acho closed by asking Goodell what kind of commitment he and the league would make to the players on issues of social justice. Goodell concluded his answer with this: "I believe the NFL's best days are ahead of it, and it's my job to help make that vision become true. And I believe we will." Again, Acho meant well, and his attempt was admirable. But he inadvertently gave Goodell a platform from which to co-opt the cause of racial injustice and to whitewash the league's role in creating misconceptions about that cause.

We can't know what's really in Roger Goodell's heart, only what he tells us with his words and his actions. Contrasted with the previous four years, Roger Goodell turned the opportunity to have an "uncomfortable conversation with a Black man" into just another chance to promote the NFL.

Dom Cosentino is a senior features writer at theScore.