25-man roster: Introducing baseball's best players from the last 25 years

theScore's Eras project began with the NBA last fall, an assessment of basketball's best 25 players of the quarter century since Michael Jordan retired from the Chicago Bulls after a second three-peat of NBA titles.

We now turn to the next installment: the best players of Major League Baseball's last 25 years. Like basketball, MLB has a major demarcation point: the 1998 season.

By the late summer of 1998, every Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa plate appearance had become live look-in television.

All but certain was that Roger Maris' 37-year-old, single-season home run record was going to fall. Sosa homered in three straight games in early September to push his total to 58. On Sept. 7, McGwire tied the record. It just so happened that on Tuesday, Sept. 8, Sosa and the Chicago Cubs were playing McGwire and the Cardinals in St. Louis.

With two outs in the fourth inning, the game paused as McGwire approached home plate for his second plate appearance. Baseballs with special holograms for authentication purposes were brought out to home plate umpire Steve Rippley. Cameras flashed. The 43,688 fans at Busch Stadium rose to their feet. Those in prime outfield seats dreamed of catching the lottery ticket of a ball.

Joe Buck, baseball's national voice of the era, was on the call along with Steve Stone.

Cubs pitcher Steve Trachsel went into his windup and tossed a low, sinking fastball toward home plate.

McGwire swung.

"First pitch rocket deep to left," exclaimed Buck, a St. Louis native whose dad was a longtime Cardinals broadcaster.

McGwire had rifled a line-drive laser down the left-field line, hardly allowing time for a dramatic call of the ball flight.

"Heeeee …," said Buck, hesitating to see if the ball would clear the wall. "He did it! He did it! He did it! He did it! …

"He did it in St. Lou!"

Buck then went silent to allow the moment to breathe: No. 62. The crowd erupted. Fireworks exploded and thumped.

In great excitement, McGwire awkwardly missed first base and had to retreat to touch it.

He was greeted by his teammates at home plate. He thrust both arms into the air as he crossed home plate and then lifted his son into the air.

The game paused as McGwire celebrated with teammates, and met with the Maris family seated along the first-base line. Eventually, Sosa made his way in from right field to embrace McGwire, who lifted his rival effortlessly off his feet. Sosa patted his back, ruffled McGwire's red hair, then McGwire placed him back on the ground. They then looked at each other. McGwire flexed his biceps, and Sosa followed. Then each made slow uppercut shadow punches toward each other's midsections.

It was baseball's ultimate single-season feat of strength.

McGwire was given a microphone to address the crowd before play resumed.

"I truly believe in fate after what's happened," McGwire said. "I dedicate this home run to the city of St. Louis."

The chase was a story big enough that many felt it helped lift the sport out of its post-1994 strike attendance recession. That summer, the grumbling about greedy owners and players was silenced.

But the feel-good celebration wouldn't last. The fact that a pair of supersized sluggers surpassed Maris' home run record in the same season led to questions that would kick off baseball's reckoning with performance-enhancing drugs.

In 2004, three years after Barry Bonds reset the record with 73 home runs, MLB and its players agreed to put PED testing in place, and the game has presumably become cleaner. Only one player, Aaron Judge in 2022, has reached the 60-homer mark since testing was instituted.

The PED era complicates our assessments of players from the last 25 years. Hall of Fame voters have struggled with the issue, which created a backlog of Cooperstown candidates as voters differ on how severely players linked to steroids should be penalized. For this exercise, we're trying to identify the very best players, but we're solely interested in how they performed against their contemporaries, not also against historical players of past eras.

Unlike some Hall of Fame voters, we aren't eliminating players tied to PEDs from consideration, but we are discounting their performance. This penalty - reducing their performance grade by 10% - is designed to remove bubble candidates but still consider the truly elite players. For instance, Bonds is on the list, but Robinson Canó's PED suspension bumps him off.

The last 25 years also included another shift that makes it especially interesting to examine: The beginning, and the whole-hearted embrace, of MLB's data age.

"Moneyball" was published in 2003 and it had a dramatic influence on how teams understood player performance and value. Some teams, like the Cleveland Indians, were employing "Moneyball"-like practices even before the A's in the late 1990s. (The A's hired Billy Beane's top lieutenant Paul DePodesta from Cleveland.) The data age led to a shift in the assessment of certain skills and measurements - most famously valuing on-base percentage over batting average. But it was also better at quantifying and appreciating defensive value, changing who plays and how often.

For instance, if this list was just based on feelings, longtime Red Sox DH David Ortiz would be an easy inclusion. But we now better understand the value of defense, and the idea that Ortiz contributed exclusively to the offensive half of the game makes him problematic for inclusion. In our methodology, he falls short, ranking 37th.

The era was also one of international expansion, accelerated by Ichiro Suzuki's trailblazing stardom. It was also an era of certain position dominance: first and third base.

This list isn't intended to be a "team" of the last quarter century. We placed no requirements or limitations on how many of a certain position could make the list - we're simply interested in the best players. Certain eras will be richer in certain positions. There are six first basemen on the list and four third basemen. There are only seven starting pitchers, though it's easier to remain healthy and compile production as a position player. This was also the era when the number of Tommy John surgeries exploded.

An important note: we only considered the last 25 years, so players who started in the majors before 1999 will have part of their careers ignored. Bonds is not only a tricky case because of his links to steroid use but because his career split between two eras. Taking his whole career into account, Bonds was perhaps the game's best hitter since Ted Williams, maybe even Babe Ruth. But most of his career played out before this era began. We're only considering his post-1998 work.

The 25-year window also makes it difficult for young stars to make the list. But elite players, still in their primes, like Mookie Betts, have accomplished enough to warrant serious consideration.

We relied on objective measurements to remove our own biases. Most of the evaluation involved combining a player's peak - their top seven seasons by WAR during the era - with their overall WAR production during the era. Membership in this club cannot just be a matter of accumulation, nor is it about a small handful of great seasons; there needs to be a balance between the two. As great as Shohei Ohtani's Ruthian-like talent is, he lacks performance volume to be included in this list.

(To create those peak and total WAR numbers, we blended FanGraphs and Baseball Reference WAR measurements.)

We also considered MVP and Cy Young awards to a lesser extent, and a player earns bonus points for each World Series ring he earned. Because baseball is such a team endeavor, with workshare so diffused, winning rings matters less - or ought to - than for the legacy of an NBA star or NFL quarterback.

Our rankings methodology ultimately resulted in a points leaderboard, and those with positive PED tests, or reported PED usage, had their points reduced by 10%.

One interesting takeaway is that earning a spot on this list appeared to be more difficult than being considered for the Hall of Fame.

For instance, Ortiz - who was elected to the Hall in 2022 - falls short, and Joe Mauer, who'll join him this summer, also didn't make the cut. Mauer is an honorable mention, one of the first five out, along with Andruw Jones, Evan Longoria, Lance Berkman, and Jose Altuve.

This is a tough club to join. It's an era that features the greatest collection of baseball talent in the game's history. And these were its best players. We'll unveil them in groups of five every day this week.

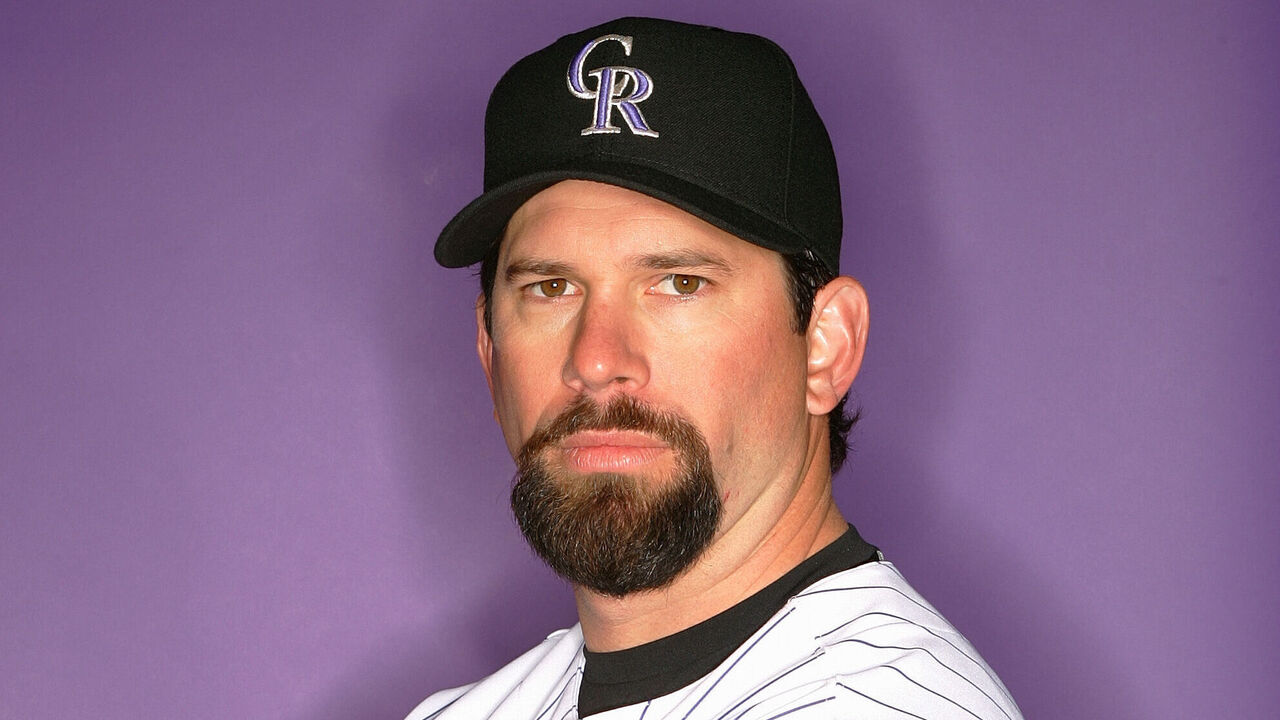

25. Todd Helton

Era teams: Colorado Rockies 1999-2013

Signature performance: On Sept. 18, 2007, Helton hit a walk-off home run against Dodgers closer Takashi Saito to give the Rockies a doubleheader sweep. It started a run of 21 victories in the season's final 22 games to clinch a playoff berth. The momentum continued through October when the Rockies advanced to their first and only World Series.

Why he's here: Helton, once the backup quarterback to Peyton Manning at the University of Tennessee, made the correct choice to pursue baseball. He led all MLB first basemen in batting average (.317) and on-base percentage (.417) during the 25-year period, which covers all but his rookie season.

The Helton haters will cry, "But he played at Coors Field!" suggesting his career numbers were too inflated from playing nearly a mile above sea level. Let's put this to rest.

Most hitters are lesser performers away from their home park because of travel, umpire strike-zone bias, and lack of familiar surroundings. Rockies' hitters have it particularly difficult as they have to adjust from not just leaving altitude, but pitches also move differently nearer sea level. The Rockies generally have some of the widest home-road splits in the sport as a result. Since 2002, they've averaged a 79.5 wRC+ on the road, worst in MLB.

Helton posted a 121 wRC+ for his career away from Coors Field.

During his seven-year peak from 1999 to 2005, he was one of the most difficult outs in baseball. He was second in on-base percentage among all batters (.442), trailing only Bonds (.515), and seventh in wRC+ (152).

The baseball media believes Helton was an elite player, too: he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in January, selected on 79.7% of ballots. He'll be enshrined in Cooperstown this summer.

24. Freddie Freeman

Era teams: Atlanta Braves 2010-21, Los Angeles Dodgers 2022-23

Signature performance: In the shortened 2020 season, Freeman finished with a .341/.462/.640 slash line, 13 home runs, and 53 RBIs to win the NL MVP.

Why he's here: While his swing's two-handed finish appears a bit awkward, lacking the grace of Ken Griffey Jr.'s one-handed flourish, few swings have been as effective as Freeman's over the last 25 years. He's slashed line drives from gap to gap, seemingly at will.

He ranks 13th among all position players in WAR for the era and 17th in wRC+. His .301 batting average ranks 23rd.

Of course, it's more difficult to hit .300 today than it was in past eras as strikeout rates have increased, and fewer balls are put in play. If we adjust Freeman's batting average relative to the strikeout environments he's played in, his adjusted average (AVG+) ranks fourth among hitters with at least 5,000 plate appearances since 1999.

The Team Canada member - Freeman's parents hail from Ontario - is simply an elite hitter. But he's also a sneaky-good athlete, as evidenced by his career-best 23 steals last season at age 33 (caught only once). He also slid across the diamond and played 136 innings at third base, with no experience there, in 2017.

Even though he's at an age when he should be declining, he's coming off the best season of his career based on WAR metrics at both FanGraphs (7.9) and Baseball Reference (6.5).

23. Buster Posey

Era teams: San Francisco Giants 2009-19, 2021

Signature performance: There wasn't just one. Seemingly every October, there was Posey behind the plate, or at it, making an impact. In the 2021 NLDS, Posey homered off Dodgers starter Walker Buehler to become the Giants' all-time postseason hits leader with 52. (He retired with 57.) A more important stat for the two-way superstar: in the postseason, the Giants were 37-19 when he was catching. Posey caught 13 postseason shutouts, the most of any catcher all time. A great player from April through September, he was the face of the Giants' even-year dynasty in the mid 2010s.

Why he's here: Posey is the best catcher of his era, elite both behind the plate and batting at it. While Yadier Molina will be remembered as the best defensive catcher of his generation - rightfully so - Posey was good enough to snap Molina's Gold Glove streak in 2016, when he led catchers with 22 defensive runs saved. He ranks seventh since 1999 in framing runs. Renowned as a leader, elite game planner, and pitch caller, he caught three no-hitters in his career, including Matt Cain's perfect game in 2012. Cain said he didn't shake Posey off once that game. The indelible image from that game is of Posey bear-hugging Cain after the final out. Posey hugged so many Giants pitchers after big moments they became known as "Buster Hugs" in San Francisco.

Of course, he wouldn't be here if he couldn't hit. And Posey was an exceptional hitter. Among all catchers who caught at least 500 games since 1999, Posey ranks first in wRC+ (130). He hit like an All-Star corner outfielder. Combine hitting, fielding, and baserunning, and Posey ranks as the No. 1 catcher in MLB in WAR since 1999 (57.6), which is even more impressive since he retired after the 2021 season with plenty left in the tank, posting a .304/.390/.499 slash line at age 34.

He trailed only Mauer in average (.302) and on-base percentage (.372) among catchers in this era, but he played nearly twice as many innings behind the plate. Posey caught more than 9,000 innings, Mauer just over 5,000. Posey was such a valuable player that a rule unofficially named after him was put in place to protect catchers from home-plate collisions after he was injured in 2011.

He's the best catcher of the century. If he played longer, he'd rank even higher.

22. Derek Jeter

Era teams: New York Yankees 1999-2014

Signature performance: Jeter recorded a number of memorable postseason moments, but the first that comes to mind for many is likely "the flip" play in Oakland during Game 3 of the 2001 ALDS. Trailing 1-0 in the bottom of the seventh inning, Terrence Long singled to right field. Outfielder Shane Spencer overthrew the cutoff man, but an alert Jeter ran across the infield, nabbed the ball outside the first-base line, and flipped it to catcher Jorge Posada, who tagged out Jeremy Giambi at the plate. The Yankees went on to win the game and later advanced to the World Series. While Jeter rated as a substandard defender for his career, his supporters will say it was the type of play advanced metrics fail to capture.

Why he's here: Some might be surprised why Jeter isn't ranked more highly, but there's perhaps no greater gap between perception and reality than any player on this list, or even in this era of baseball. Had Jeter been drafted by, say, the Cincinnati Reds with the fifth overall pick in the 1992 draft - the Yankees took him at No. 6 - and put up the same numbers, he'd still be remembered as a great player, but perhaps not one perceived as an inner-circle Hall of Famer.

Jeter was a great hitter for a player stationed in the middle infield. He accumulated 2,877 hits in the era (3,456 hits for his career), which ranks fifth among all players since 1998, and tallied a .310 average.

Among shortstops to play in at least 1,000 games from 1999 to 2023, he ranks sixth in wRC+ (120).

Jeter was part of five Yankees' World Series title teams, including three during this 25-year period. He played an integral role on those championship clubs, and so receives a bonus for each of those titles. But his overall WAR productivity was weighed down by his tremendously poor glove.

In the 25-year period, Jeter was not only the worst defensive performer at his position, but the worst in baseball relative to his contemporaries. He racked up a staggering -162 Defensive Runs Saved. Only one other player in baseball reached negative triple digits over that period: Prince Fielder at first base. And it's not just DRS. He rated as the third-worst defender in baseball and worst shortstop over that period by Ultimate Zone Rating, and the worst by range rating. Despite his poor defense, "The Captain" never played an inning at another position even when a better defensive shortstop, Alex Rodriguez, arrived in New York.

Jeter's signature defensive play is a microcosm of the perception that dominates his legacy. He perfected the jump throw, but those highlights would be routine plays for other shortstops.

21. Scott Rolen

Era teams: Philadelphia Phillies 1999-2002, St. Louis Cardinals 2002-08, Toronto Blue Jays 2008-09, Cincinnati Reds 2009-12

Signature performance: Rolen goes down in Cardinals' lore for his home run off Justin Verlander in Game 1 of the 2006 World Series and for his .421 average in the series, which helped St. Louis to the title.

Why he's here: Inducted into the Hall of Fame last year as the only member via the BBWAA voting process, Rolen was an exceptional two-way player. His all-around game is perhaps more appreciated by modern metrics than it was when he was playing. That said, he stacks up well by traditional measures, too: he made seven All-Star appearances, won eight Gold Gloves, and earned a Silver Slugger in the era.

He ranks ninth overall in DRS since it began being recorded in 2003, and third among third basemen, trailing only Adrián Beltré and Nolan Arenado. At the plate, Rolen posted a 119 wRC+ and hit 260 home runs.

He was essentially the same offensive performer (119 wRC+) as Jeter, but was a tremendous asset on defense instead of being a liability.

Rolen accounted for incredibly balanced production. His 58 WAR in the period made him very worthy of the Hall of Fame, but he also ranked only fourth among third basemen in the era.

Follow the unveiling all week long. Tuesday: Nos. 16-20.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.