Eternal doom of small-market owners' minds leaves baseball fans cold

What happens when a baseball leader says the quiet parts out loud?

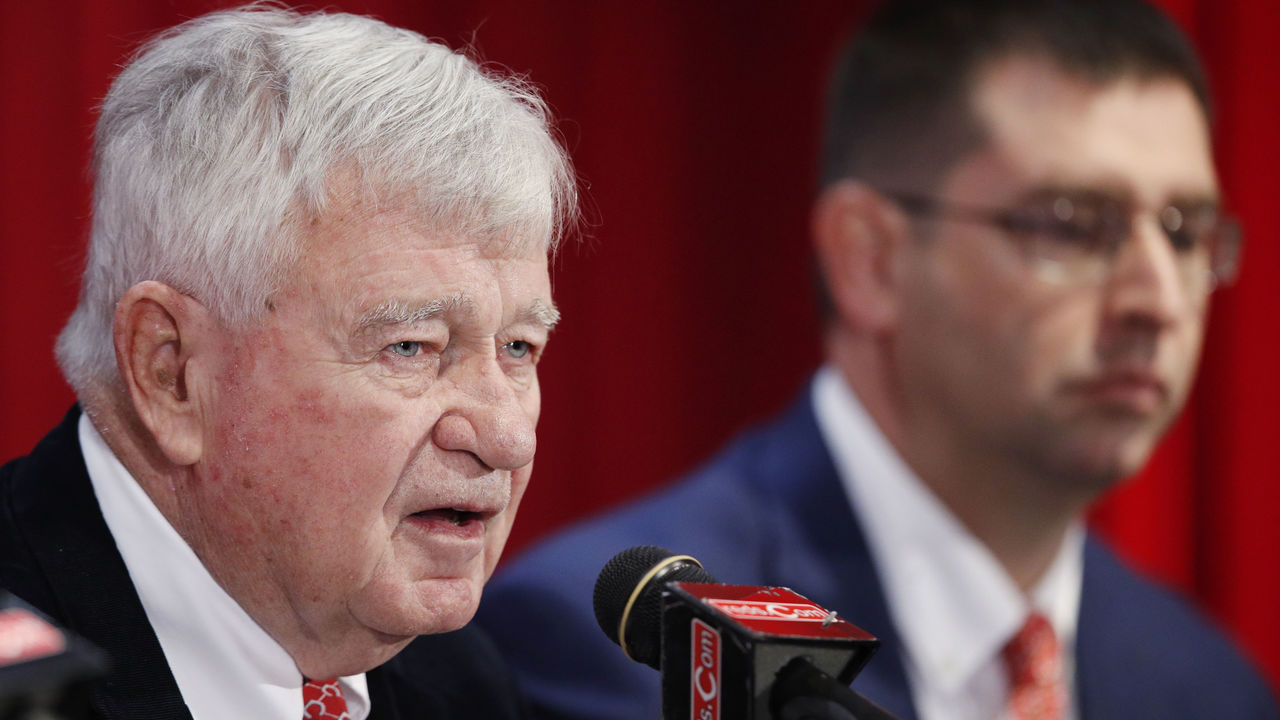

Phil Castellini, the Cincinnati Reds team president, is the son of team owner Bob Castellini. The family's wealth, made in fruits and vegetables, dates back to the 1890s. The senior Castellini bought the club in 2005. In a radio interview this week prior to the team's home opener, Castellini opened the curtain a little.

The Reds, as you might know, disappointed many of their fans by shedding quality players like Sonny Gray, Tucker Barnhart, and Jesse Winker this offseason, citing payroll challenges. The Reds finished sixth overall in the National League last season and what fans thought would be the beginning of a contention window quickly disappeared.

On WLW-AM, host Mo Egger asked Castellini why fans should "trust" ownership after 15 years with four playoff appearances and no division titles since 2012. It came near the end of a 12-minute interview in which Castellini said the pandemic broke the Reds' revenue streams and necessitated the recent selloff.

"Well, where are you gonna go?" Castellini said. "Let’s start there. Sell the team to who? That’s the other thing - you want to have this debate? If you want to look at what would you do with this team to have it be more profitable, make more money, compete more in the current economic system that this game exists (in)? It would be to pick it up and move it somewhere else. And so be careful what you ask for. I think we’re doing the best we can do with the resources that we have."

The answer lays bare the disconnected relationship we see between fans and owners in some markets.

Let's begin where Castellini began in addressing fans' complaints as expressed by Egger:

Where are you going to go?

That's one of the quiet parts said aloud.

One of the reasons why MLB clubs are such great businesses to own - much better than the stock market - is because to own a team is to own part of a legal territorial monopoly in the industry of Major League Baseball, which enjoys national interest and a federal antitrust exemption. It's a lucrative investment and a safe one. While COVID-19 may have hampered yearly revenues, it didn't affect franchise values.

The owners also enjoy the hold their asset has on fans' emotions and loyalties, which are tied to summertime traditions within a region. To own the franchise name embroidered on the front of the jersey is to possess something different than a truckload of tomatoes (even if you have no competitors).

There are no local major-league alternatives within most cities. The Castellinis know most fans aren't going to go anywhere.

Bob Nutting in Pittsburgh knows this, too, as do ownership groups of other small-budget clubs.

The Reds still sold out their home opener this week. So did the Guardians up in Cleveland.

As upset as fans might be during an offseason of stripping down a roster (Cincinnati) or not spending on one (Cleveland), most always come back. Fans might stay away from the ballpark more often during a down season, but as soon as the club is relevant, they return.

Are some MLB owners missing opportunities to grow the sport regionally and nationally? Absolutely.

Could a more compelling product draw in more new fans? Yes.

Should owners be worried about their aging fanbase? Indeed.

MLB's attendance, in fact, has gradually been declining since the 2007 record, down 13% from its peak in 2019, the last full, non-COVID season.

But many small-budget owners seem content to not work to maintain loyalty among their fans. That loyalty is already baked into the system. There's little incentive to improve the on-field product. There's nowhere for fans to turn except to tune out until things get better.

Castellini knows this and so do other owners. It's hardly a secret, but one rarely vocalized.

What would you do with this team to have it be more profitable, make more money … ?

One answer would perhaps be to create a more compelling product.

The Castellinis are entering their 17th season of team ownership, and have made the postseason only four times, never advancing beyond the Division Series round.

Reds attendance ranks near the bottom of the league regularly under their stewardship, a far cry from the records set during the Big Red Machine era. Only once have the Reds finished higher than 10th in attendance in the National League, in 2014, after postseason berths in three of the four previous years. Since then they haven't finished higher than 11th.

The comment speaks to something the public already suspected was true, and Castellini simply offered verification: teams make money regardless of performance. Team owners enjoy lucrative revenues before even selling a ticket.

Revenue sharing has never been a better deal for smaller-market clubs. In MLB, 48% of all clubs' net local revenue is placed into a pot and split among teams based upon a formula that results in money moving from larger-market teams to smaller ones.

Along with increasing national media dollars, smaller-market clubs are generally earning more than $100 million per year in revenue before ever selling a ticket or hot dog.

Yet nine clubs began this season with payrolls under $100 million.

Something that was overlooked nationally during the hoopla of opening week was a story by Mark Belko of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. The newspaper obtained and analyzed documents related to the team's PNC Park rental agreement and reported that "the lion's share of the Pirates players' payroll in many years since 2007 has been covered by ticket and concession revenues - even before accounting for the millions that Pittsburgh's team collects from TV and Major League Baseball."

Pittsburgh's payroll has risen and fallen with gate-generated receipts. TV dollars and revenue-sharing dollars are going elsewhere, the paper found.

Pirates owner Bob Nutting remarkably said in 2019 that payroll wasn't "controllable." Nutting was seemingly then, too, tying payroll to tickets and concession sales, which can rise and fall based on on-field success.

The MLB Players Association even filed a grievance in 2018 over the lack of spending by four teams, including the Pirates, when it was known they were earning revenue-sharing checks.

Owners' payroll choices follow an elemental question of modern capitalism: do you spend money to make money, or do you cut expenses to improve your margins? One of those choices isn't fan-friendly, and it must be noted that there aren't too many businesses in which an owner doesn't have to invest in the actual product - the team - in order to make a profit. In fact, the most favorable option for fans would likely be what's currently happening in New York with the Mets: Steve Cohen is as close as we've ever come to an owner treating his team like an actual fantasy team.

In the competitive balance tax era, the gap between big and small spenders is only growing.

In 1995 and 1996, the last years before the competitive balance tax was implemented, the top five MLB payrolls were a combined 2.4 times and 2.5 times greater than the lowest five, respectively.

In 2010, the gap was 3.3 times.

In 2021, the gap was 3.6 times.

This year, the Opening Day gap was 4.9 times.

It's difficult to believe ownership groups are not doing extremely well in terms of not only franchise valuations but cash flows (even if those reported flows are warped for accounting purposes).

Despite lucrative media dollars and shared revenue, the Guardians' payroll is more than $25 million less than it was in 2001, not even accounting for inflation.

Be careful what you ask for.

Castellini claimed payroll was constrained by market size and the only way to improve it would be to move to a larger market - to "pick it up and move it somewhere else." Whether it was rhetoric or an outright threat, it was chilling nonetheless.

Teams have been using other cities to gain leverage for new stadiums for decades, perhaps since Cleveland Municipal Stadium became the first stadium built with public money in the early 1930s, setting the taxpayer-funded model.

Hamilton County, Ohio, taxpayers funded the construction of Great American Ball Park, which opened in Cincinnati in 2003.

Two of the few clubs without new stadiums, Oakland and Tampa Bay, are using the threat of moving to Las Vegas, Montreal, or elsewhere to try and gain leverage.

Fans and cities have no leverage - there's no competing league. It's been more than 100 years since the Federal League popped up to poach talent and build new parks.

Castellini did later issue an apology statement. But he already said the quiet parts out loud, utterances that many fans - especially those whose loyalties are tied to smaller-market clubs - suspected all along.

It was more evidence of a toxic relationship between some MLB owners - especially those low-spending owners - and their fans. Those relationships were exacerbated by the lockout, which shortened spring training. And this hostile dynamic doesn't exist in other sports as regularly, or to the same degree, because of those sports' different spending structures.

Baseball lacks a payroll floor, which at least gives the appearance of a level playing field. Floors also provide the added benefit of compelling teams to make free-agent signings and trades, to keep year-round interest, and to build hope.

While payroll and wins are only loosely correlated in baseball, there's a perception problem for owners who don't spend - that they don't care and don't feel the need to compete. We saw that frustration boil over in Cincinnati this week.

Whether or not a cap-and-floor system would be good for MLB players is a different question. (I suspect it would be for most players, but the union was against any such concept that came with a lower tax threshold during the lockout negotiations.) It would certainly be good for building fan interest and the game itself, reducing the angry words and rancor leveled at non-spending ownership groups.

Until owners are forced to meet a certain level of payroll, the kinds of selloffs the Reds undertook will continue, as will calls to move or sell teams. The toxicity between certain fans and certain owners will go on. And once in a while, someone will state the quiet parts out loud.

Castellini is right about one thing, though: Where will disenchanted fans go? They have no choice but to tune in or turn elsewhere.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.