How important is running the ball in today's NFL?

This is going to sound counterintuitive just days after the New England Patriots attempted the fewest passes in an NFL game in 47 years to defeat the Buffalo Bills on the road, but "establish the run" is still a phrase that deserves to die.

Bill Belichick's game plan worked on a night when the swirling winds made it difficult to throw downfield. But there's nothing sustainable about the approach, and there isn't much to take away from New England's win.

If anything, the way the Patriots won says more about New England's defense and Buffalo's offense. Yes, the Patriots rushed for 222 yards on 46 carries, a robust average of 4.8 yards per carry. But the Patriots also scored just 14 points and picked up only 10 rushing first downs. Sixty-four of those rushing yards came on a single play. The fact is, the Bills twice had the ball in the red zone over the last eight minutes but came away with nothing. Buffalo's multiple self-inflicted mistakes played a huge role:

- On the first of those two fourth-quarter red-zone drives, Josh Allen took a brutal sack on second-and-goal from the 6 that lost nine yards.

- Two plays later, Tyler Bass missed a 33-yard field goal into the wind.

- On the second fourth-quarter red-zone possession, the Bills had second-and-9 from the 13 when Allen had his back-shoulder throw to an open Stefon Diggs sail out of bounds near the goal line. As "Monday Night Football" analyst Brian Griese noted after the play, the wind was blowing across the field in that direction, which meant Allen was better off throwing to his left in that situation.

- Tight end Dawson Knox was whistled for a false start on the next play.

- On third down from the 18, Allen put his head down to evade a collapsing pocket and didn't see a wide-open Diggs over the middle near the first-down marker at the 5-yard line. He tried to jam a pass toward a covered Knox instead. It fell incomplete.

Why rehash all this now? Because what we learned is what we already know: the margin for error in an NFL game is incredibly small.

The fact remains that passing the ball is more efficient than rushing, particularly on first and second down, and there's a mountain of data out to prove this. From Ben Baldwin's analysis at Football Outsiders on whether defenses need to rest to the more recent comparison from Eric Eager of Pro Football Focus on run-blocking and pass-blocking success, more research supporting the importance of passing continues to be published.

Passing is more efficient even for the Philadelphia Eagles, Indianapolis Colts, Baltimore Ravens, Cleveland Browns, Tennessee Titans, and, yes, the Patriots - the league's top six teams in rushing yards. In fact, according to Baldwin's database, every NFL team is more efficient on early downs when passing this season except for the Jacksonville Jaguars and San Francisco 49ers - albeit barely.

All but nine teams pass more often on first and second down than they run it - with good reason.

To be clear: this does not mean running the ball has no place in today's game. However, in the last decade, the rules have changed multiple times to protect passers and pass-catchers; teams and coaches around the league began to use analytics as a decision-making tool. As a result, NFL offenses became increasingly pass-heavy. Contrary to a popular misconception, analytics do not dictate which decision a coach or team will make, it is simply information used to find inefficiencies to guide certain decisions. Which is an important distinction.

The Patriots, for example, have used analytics to tailor their running game to counter the lighter, faster defenses that have proliferated due to the new, pass-oriented NFL. New England's entire offense - from personnel to formations to play-calling - is predicated on this; it's not simply a matter of handing the ball to Damien Harris or Rhamondre Stevenson 50 times a game and hoping for the best, as a coach for another team recently explained to Sports Illustrated's Albert Breer.

"They're very committed to the run game, the offensive line's good and they're really physical," the coach told Breer. "You can tell they’re well-coached, they're on their shit in the run game, and with the amount of 21-personnel (two backs, one tight end) they run at you, it's tough. It's different than what you see from other teams. No one, other than maybe Baltimore and San Francisco, runs it more than they do."

Part of the Patriots' aim, as Breer also pointed out in that same story, is to create a structure around quarterback Mac Jones that gets him into manageable third downs as much as possible. Jones is a rookie, and New England is developing him by making the game easy for him.

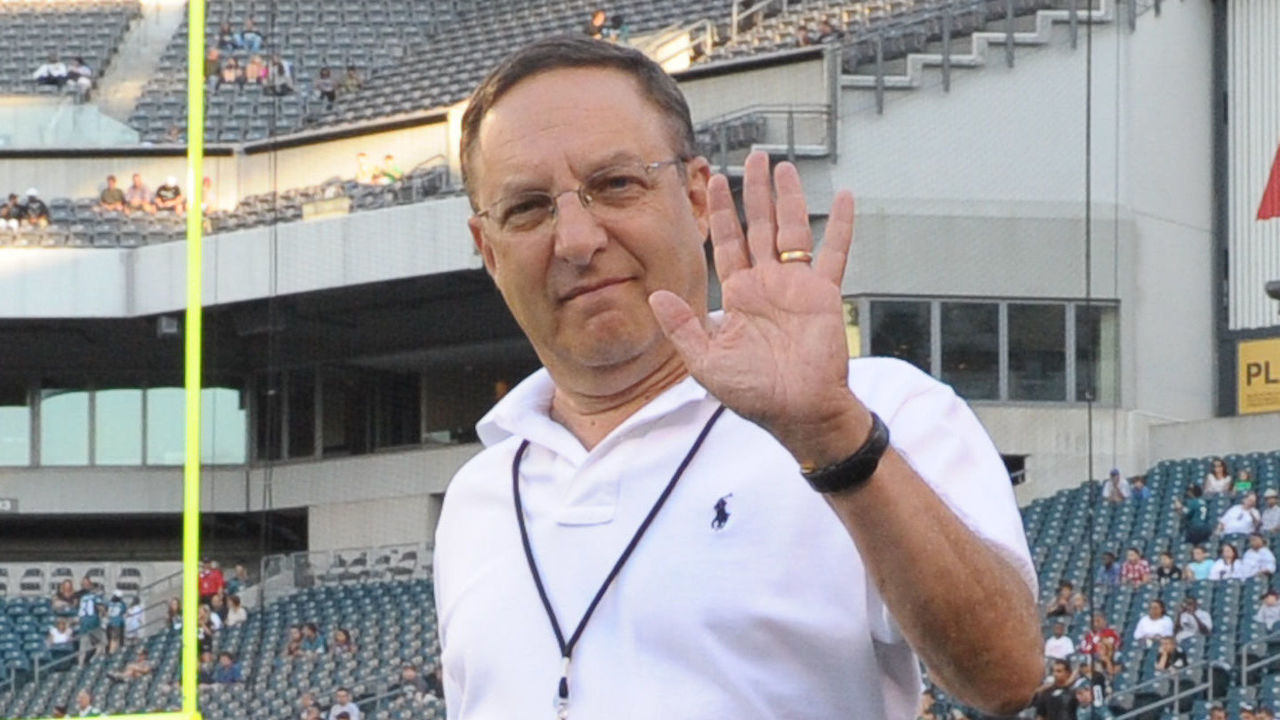

Still, there remains a stubborn insistence that every team has to establish the run or run the ball to win. For more insight on this, theScore spoke to Joe Banner, a former front-office executive with the Eagles and Browns. Banner was with the Eagles through the entirety of Andy Reid's tenure as head coach - a stretch that included five trips to the NFC Championship Game and a Super Bowl appearance.

The Eagles were consistent winners at the time, but they also embraced a pass-heavy approach rooted in data analysis that defied much of the conventional wisdom around the importance of running the ball and the need for offensive balance. Banner remains a big believer in the primacy of passing while noting that running the ball has its place.

The following conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

What place does the running game have in today's NFL?

Banner: Running the ball does have a series of positive effects, depending upon where in the game you may be. It does, in fact, contribute to some sense of physical dominance, which has value. It does serve the purpose of shortening the game, if and when that's something you want to do. It does help keep the defensive line honest, which makes it easier for the offensive line to block.

Those things are overridden by how important it is to get the lead and have the lead at halftime, and how massively more likely that is to happen if you come out passing. The phrase I always use is, "You pass aggressively early to get the lead and you run more and more as the game goes on to keep the lead."

I kind of frame that as an ideal, but obviously who the opponent is and all these other kind of things matters. But generally speaking, you want to be trying to be aggressive, get the lead. This extends not just to play-calling, but team-building. So if you want to do what I just said, you want to have a really good defensive line to prevent other teams from coming from behind.

The Eagles are an interesting example here. They started 2-5 and were barely running the ball at all, and then they started running a lot more and they've won four of six.

Banner: Yeah, but when (Gardner) Minshew came in (last week against the New York Jets), they went back to the pass, they kept winning, so I'm not really sure we have a cause and effect. But here's my bigger point: if you look at the wins, they were not against very good teams. It was against somebody like New Orleans who was playing their third-string quarterback.

I just question what's the priority this year … The big priority is positioning themselves for three years from now, when that team has a serious chance to be a Super Bowl contender because that's not happening this year - at least I don't believe so. I would be playing (Jalen) Hurts, but I wouldn't be using him primarily as a runner because that doesn't help you answer all the questions you need to know for the long run. I would be playing him, and I would be using a normal offense with a mixture of runs and passes. It's pretty infrequent that 40 runs and 14 passes wins the game unless you get a big early lead.

We know that Hurts can run an offense that's primarily run-based very successfully. But if we want to know whether he's the long-term answer, between now and the end of the year we have to at least have an informed opinion on how good he is with the passing part of it.

You can't just be run-oriented; you have to have somebody that can do both, like a Kyler Murray or somebody like that. Look at Lamar Jackson. He's somebody who I think is spectacular at the running part of the game, but he's just OK in the passing part of the game. (The Ravens) can be good; they'll have a real hard time being great if he doesn't fix that.

What do you make of what the Colts have done with Carson Wentz, given that they have Jonathan Taylor and that great offensive line?

Banner: I'm impressed that they've brought him along the way they have. There was a point in the season where people were saying he's making a lot of progress and I wasn't completely sold on it. But I'm more so now.

But they are usually throwing it a decent amount - not every game. They're less consistent about this than I think they should be (the Colts' pass rate on early downs is 50.7%, per Baldwin's data), but they do come out throwing in a lot of games to get the lead. The same thing is true with the Browns, who everybody thinks is a running team. The Browns throw early (49.2%) to get the lead and then they run more and more as the game goes on.

That's the thing. People look at the volume stats like rushing yards but don't realize how much these so-called run-first teams are throwing on first and second down.

Banner: Exactly. Almost 80% of the time the team leads at halftime, they win the game. Think about that. That should inform your play-calling, how you build your team, everything. We need to get a team that can get off to a fast start, and we need to have a strong enough defensive front that people have trouble coming back on us.

None of this means that you have to throw on every play to maximize your efficiency, right? There is clearly a place for the running game.

Banner: When I was in Philly with Andy Reid, we kind of looked at this question. We believed that if you ran about a third of the time or a little bit more than that, that was enough to achieve the goals that I listed earlier. The idea of being balanced we thought was ridiculous. The idea of making sure you're mixing in enough run to keep everybody fresh, assert some dominance, maybe if you have the lead to shorten the game - we believed in all those things.

I don't remember a time when Andy's pregame speech didn't include a segment on how important it was to get a fast start in a game.

Why do you think coaches and teams talk so much about emphasizing the run? Matt Rhule wants the Panthers to run it more often, and Art Rooney II declared last January that the Steelers had to make "a commitment to the running game." Why are teams still stuck in this mindset, given the information that's out there?

Banner: Change is slow. And people want to find reasons to affirm their pre-existing beliefs. By the way, when I say "people," I mean everybody, including myself. Your inclination is to interpret things in a way that affirms or confirms what you think you already know.

I debate this with a lot of people. If you believe in the run, you'll actually find a way that it's impossible for you to be wrong. If the running game is working, you say, "See, look at how good the running game is working." If the passing game is working you can claim it was because of the running game that led to play-action success. You can set it up in a way that you can't possibly be wrong. Whatever's working you say it's because of the run when obviously that's not true.

And play-action isn't dependent on being able to run.

Banner: The perception of your ability or willingness to run does enhance your ability to run play-action passes. That said, you can run a play-action pass on the first play of the game and it's going to be as effective as if you spent the first 20 plays establishing the run.

Play-action passing works, period. You don't have to set it up, you don't have to run to tire everybody out, or anything. You just have to call play-action, it's highly likely to work.

Dom Cosentino is a senior features writer at theScore.

HEADLINES

- Report: Anthony Davis expected to sit out rest of season with Wizards

- Former Jets 1st-round pick Darron Lee charged with 1st-degree murder

- Jenkins leads Pistons' rout of Knicks in final game as two-way player

- Brady pledges late support for Patriots in Super Bowl

- McGwire returns to A's as special assistant to player development