Week 9 Film Study: Texas' pass D struggles, Clemson gets creative

Here's a look at some of the more intriguing film-related developments from Week 9 of the college football season.

Texas gives Cornelius too much time

Todd Orlando's received a ton of praise - in this column and elsewhere - for turning around Texas' defense. He's at the forefront of innovation when it comes to scheme concepts, and he's made Texas a top-15 defensive unit for the first time since George W. Bush was in office.

But Orlando got his game plan really, really wrong against Oklahoma State in the Longhorns' 38-35 defeat, as he arrived in Stillwater and ostensibly said, "We're going to do us."

In the contest, Texas used its traditional quarters-match approach, which looks to limit explosive plays. It sprinkled in some Cover 3 variants and press stuff here and there, but mostly lined up with two deep safeties and dropped other defenders into zones where they could read quarterback Taylor Cornelius' eyes.

Ok. I get it. Cornelius had struggled with inaccuracy and boneheaded decisions this season. And there's a line of thinking that spot-dropping into zone against that type of quarterback is actually more aggressive, as it means everyone is watching and waiting to pounce on mistakes while forcing him to throw to landmarks rather than to receivers in one-on-one battles.

However, I disagree, particularly when that tactic is paired with just a three-man rush. That's what Texas did - and by rushing only three and dropping into zones, the defense gave Cornelius all day to sit back and survey the field:

That's way, way too easy for any third down.

Texas should have played press-man coverage. By bodying up receivers, the defense would have forced Cornelius to thread the needle and make perfect throws against tight coverage.

Nevertheless, Orlando stuck with zone, and Cornelius continued to feast. Even on difficult throws - when he had to drop the ball in front of a safety and over a linebacker - he shone. It’s just easier when your job is to spot open orange shirts and throw to them, particularly when there’s little pressure in your face.

Cornelius was able to fling the ball to a spot on the field and let his guys go create after the catch.

Again, not disrupting the release of Oklahoma State's receivers was the greatest sin. You can play zone, fine. But make sure you add in one of two elements - either a serious pass rush or a press-and-trail technique, in which a defender jams a receiver's initial release and then drops to his spot.

As seen below, gifting receivers like Tylan Wallace and Dillon Stoner a free release is asking for trouble:

Nobody laid a finger on Wallace. The corner played with outside leverage, expecting help from the middle of the field. Yikes.

This angle better illustrates the point:

The cornerback had no chance of keeping up once the long-legged receiver hit full stride. He needed to try disrupting Wallace's release at the line.

Orlando did make some adjustments during the game, as he used more fire-zone blitzes that drop linemen into coverage while blitzing other defenders. This was likely predetermined to some extent, as the hope would have been to let Cornelius see coverage ghosts and then start messing with who drops to where.

It didn’t work. Cornelius just kept throwing to whoever was open with impressive timing and anticipation:

It wasn’t just tactical errors by the Longhorns, either. They were guilty of simple mistakes - everything from missed tackles to poor angles to struggling to identify OSU’s bootleg and move concepts. When all was said and done, Texas had blown a game it should have won.

But regardless of those individual errors, the tactical elements will bother the Longhorns' staff just as much (don’t expect them to admit it, though). Rarely in real time do you see such a schematic miscalculation. Orlando's one of the best in the business, and I’m guessing he'd want another crack at this matchup.

Clemson's 600 pounds of offensive backfield

And now, for my favorite play of Week 9:

Quick question: How exactly do you stop more than 600 pounds charging toward you? You don’t.

For this play against FSU, Clemson stuck two of its (massive) star defensive linemen - Christian Wilkins and Dexter Lawrence - in the offensive backfield. Wilkins then scored the touchdown by taking the handoff and displaying the combination of twitch and wiggle that makes him such a menace on defense.

Unfortunately for Lawrence, he didn’t get to do a whole lot as the fullback. Clemson's offensive line mauled FSU's front as Wilkins coasted into the end zone.

Overall, No. 2 Clemson put the smackdown on a beleaguered FSU side in a 49-point victory. Some FSU players even quit during the game, according to Seminoles head coach Willie Taggart.

Running a heavy offensive set with the heaviest of defensive linemen was the height of rubbing it in. Kudos, Dabo Swinney.

Arizona State uses 'diamond' to perfection

When you think of offensive innovation, I’m not sure Herm Edwards comes to mind. But on Saturday, Edwards' Arizona State team bullied a gifted USC defense by using a combination of sheer brutality and schematic wizardry, emerging with a 38-35 win.

The Sun Devils are a classic ground-and-pound offense, built in the image of their veteran head honcho. But they’re also employing new-age looks with all kinds of modern pace-and-space wrinkles thrown in.

Offensive coordinator Rob Likens doesn’t run many plays, but he dresses them up in a variety of formations. You know one of eight runs is coming, but it’s hard to get a read on exactly which one it is. That deception - combined with the threat of quarterback Manny Wilkins as an option runner plus play-action passes - means this offense can be deadly.

Likens has borrowed bits and pieces from the top offensive minds in the country. There's Chip Kelly’s double-stack, which is designed to declutter the box:

There's this snazzy condensed look in which a pair of slot receivers essentially act as double wings:

And then there’s a formation popularized in recent years by Oklahoma’s Lincoln Riley - the "diamond."

The diamond - or a full-house formation, depending on your coaching parlance - has the quarterback lined up in the pistol with a running back behind him. The quarterback's also flanked by a pair of extra players.

Depending on your personnel grouping, those extra players could be tight ends, fullbacks, running backs, H-backs, receivers, or any combination of them.

The diamond look gives an offense all the benefits of a classic two-back set - the endless play-design possibilities and a balanced formation - without any of the drawbacks. And a defense is forced to respect the possibility of a quarterback run or an option element on each and every play.

Plus, as with any pistol run, the quarterback doesn't need to turn his back at the mesh point (where a potential handoff would take place). He can keep his eyes fixed downfield, making run-pass options (RPOs) and option reads much easier.

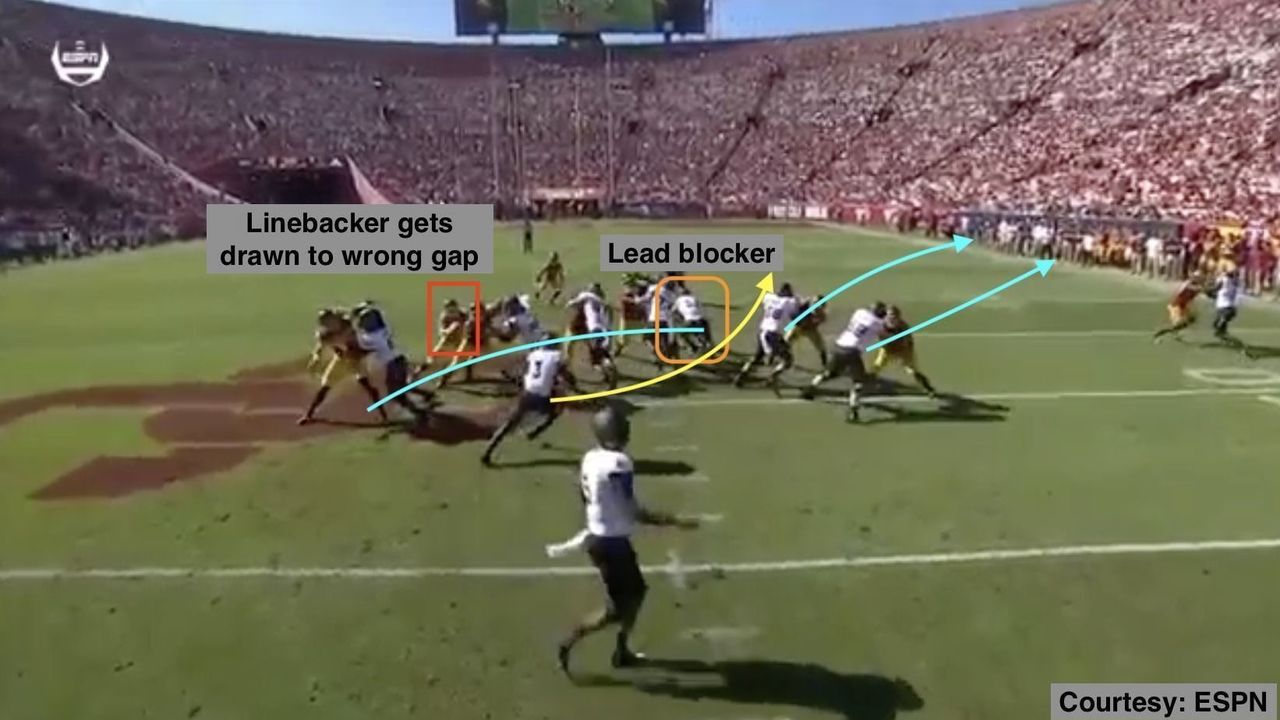

The Sun Devils torched the Trojans on the ground and through the air out of the diamond, which allows a play-caller to dial up something as simple as a lead zone (with two more lead blockers tacked on for extra effectiveness), or something more complex with lots of moving parts.

That means for a defense, the onus is on the linebacking corps and the rotating safety to diagnose plays and stay disciplined. On Saturday, USC was missing linebackers Cameron Smith and Porter Gustin and safety Marvell Tell III - the team's three defensive captains - and it showed.

ASU rocked USC’s front early. Linebackers started guessing on run plays. Passing lanes opened up. Wilkins sucked in linebackers with play-action passes before slinging the ball behind them:

Arizona State did a marvelous job of modulating its tempo. The unit would go no-huddle, but not always fast. It would get to the line, take its time, and make sure to get into the right play. But catch USC in the wrong personnel grouping, and the offense would go fast.

It was a schematic and physical beatdown. ASU did the little things excellently. USC didn’t.

That’s as simple as it gets on a short-yardage run, using an insert zone with a pair of lead blockers. And the diamond formation allows the pair of lead blockers to charge off the ball and angle their bodies to seal a crease.

As seen on this angle, the ball-carrier was untouched until the second level. You won't see a more picture-perfect example of positional and physical leverage:

Arizona State's defied expectation this season. Edwards has set a standard. He wants a tough football team, and his team is tough on both sides of the ball. But the offense also has the kind of schematic diversity needed to compete against teams with superior athletes.

Arizona's suffocating 3rd-down D

Oregon headed to Arizona on Saturday with one of the best third-down conversation rates in the country. The nation’s best quarterback, Justin Herbert, will do that for you.

Meanwhile, Arizona's inexperienced defense had struggled on money downs. Blown coverages, missed assignments, and bad tackles in open space had forced defensive coordinator Marcel Yates to use vanilla concepts on a down that usually sees coaches get more creative. The unit entered Week 9 ranked 83rd in third-down defense.

So, of course, that all flipped on Saturday. That’s college football.

Arizona stifled Oregon on third downs all night. The Ducks failed to convert any of their first seven opportunities and finished just 3 of 16. The game got away before they blinked, as the Wildcats won 44-15.

Yates, who's known as an attack-oriented play-caller, hadn't been very aggressive earlier in the season - largely due to his young squad - but his vision's begun to take shape in recent weeks.

He's been running a number of combination coverages, pressing one side of the field in man and zoning the other. The goal is to disrupt the receivers' timing and the quarterback’s anticipation, which ideally forces the latter to take extra time to diagnose the coverage, allowing the pass rush to get home.

It worked perfectly against Herbert. Oregon’s wide receivers couldn’t separate from the line of scrimmage and their quarterback had no easy, quick throws. Arizona’s linebackers and safeties clamped down on everything underneath.

This was a defense playing with no fear. The unit was aggressive and jumped everything underneath. Yates demonstrated some formational flexibility up front by showing Herbert a bunch of different looks, while keeping the coverage largely the same in the secondary.

And when Herbert looked for an outlet underneath, the Wildcats' second-level defenders were already tearing toward the ball:

Herbert had a couple of options - he could bail out of the pocket and look to extend plays, as he did on a costly interception, or he could hold onto the ball and hope for a defensive error. But the young defense didn't make many mistakes.

As the game wore on, Yates got even more aggressive. He cranked up the pressure on Herbert, realizing that time in the pocket was the only thing that could slow down his defense:

The pressure was possible because Oregon’s receivers were unable to separate outside. The Wildcats ran a bunch of off-man coverage, with corners encroaching on the line of scrimmage as soon as the ball was snapped to get a jam on receivers.

In essence, one corner would bluff zone coverage, and then apex the boundary receiver. Herbert had no idea who was coming or going. His receivers had no idea what type of coverage they were facing.

Watch the bottom of the screen here:

When you combine that with elite linebacker play - and Arizona got elite linebacker play on Saturday - not a whole lot can go wrong. Yates asked his 'backers to play "see ball, get-ball" football. That’s how linebackers want to play - it’s downhill and aggressive. It’s also hard, particularly against an Oregon side that wants linebackers zipping downhill.

So, Arizona’s linebackers had to play with a cautious aggression, allowing Oregon’s man-beating concepts to pass. Below, watch as Arizona’s middle linebacker sorts through the trash around him, and then quickly closes in to make a crucial third-down stop:

The linebacker was forced to work over the top of his own slot defender, who was hauled up in press coverage. Then he had to pass off a drag route that was intended to force him into one of his own teammates (that route was open, by the way). Then he had to readjust, plant, and fire on the second crossing route.

Perfection.