March melody: How the iconic theme music for madness was born

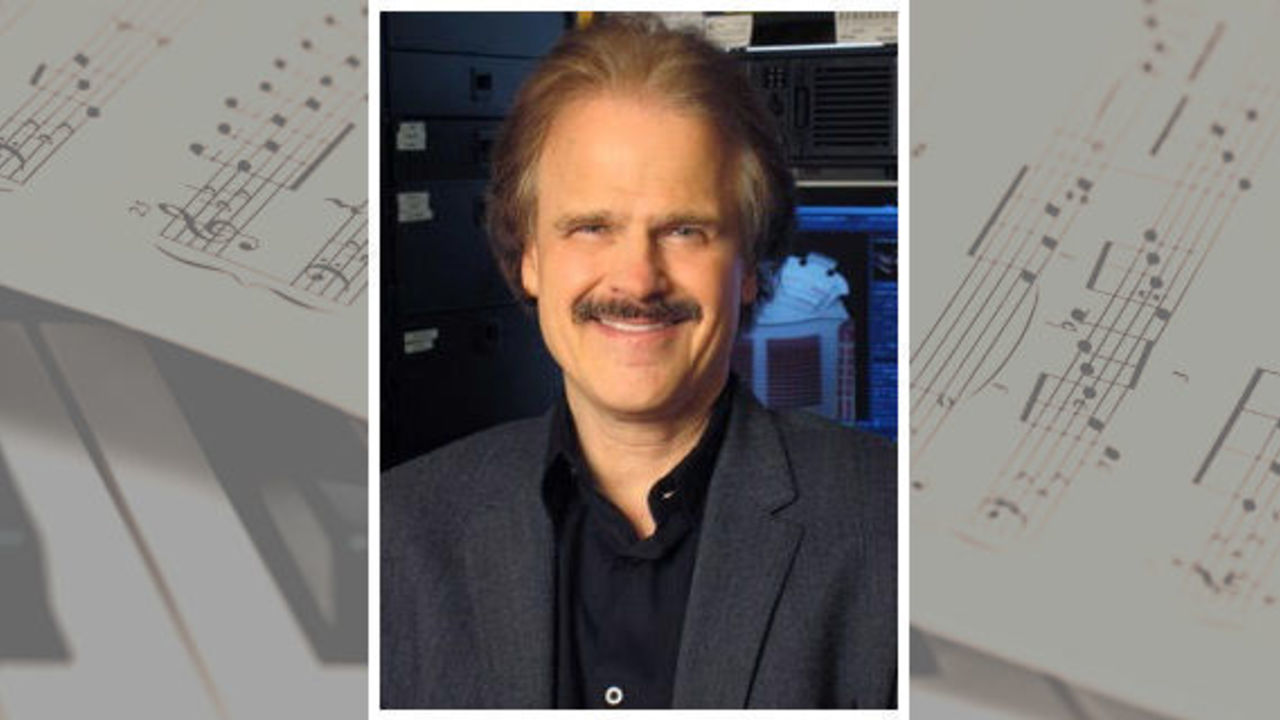

Many of us have a particular tune stuck in our heads every March - a melody we can't escape, nor do we want to. It came into existence starting with a phone call to composer Bob Christianson's New York apartment 30 years ago.

Calling from a few miles uptown was CBS executive Doug Towey. Christianson had worked with him before, and they were on friendly terms. The late Towey made a pitch: Would Christianson be interested in writing a theme song for CBS's coverage of the NCAA men's basketball tournament?

The network had broadcast tournament games since 1982, but it was entering the third year of a seven-year, $1-billion deal that gave it exclusive rights for the entire tournament. It wanted a new theme, one with added gravitas and energy, to debut a few weeks later with the 1993 tournament.

Towey said he'd reached out to a handful of composers, and there would be a competition. "We'll give you a week. Is that OK?" Christianson recalls Towey saying.

There's never been much turnaround time in creating sound for the television industry, Christianson says. This was normal. When he was composing for "Sex and the City," he regularly received assignments to score a five-minute scene at, say, 8 p.m. with instructions to have it completed the next morning.

Intrigued by CBS's challenge, Christianson agreed.

He was 42. He'd written hundreds of commercial jingles by then, and a number of sports themes, too, including ESPN's original NHL theme. (When the network regained national NHL broadcast rights last season, Christianson's refresh of the theme won him an Emmy.) He's conducted and composed larger productions on Broadway and television, too. He's not a one-hit wonder.

How was such a tune born, especially on deadline? And not just any theme, but one that Christianson defines as "an earworm … Something you cannot get out of your head. The loop keeps going on." He can't quite recall the details about when the first notes materialized in his head, but he knows what his process was.

He never begins by sitting down at a keyboard.

"Over the years, I've learned to not get my initial ideas at the piano," Christianson said in a conversation with theScore last week. "Only because I've played piano for so long that my fingers basically go where they want to based upon muscle memory."

The inspiration, a promising pattern of notes, often arrived when he was walking the New York sidewalks that connect the brick townhomes of his neighborhood in Chelsea.

"I just walk around and think of anything other than writing the theme," Christianson says. "That's usually when the best ideas come in.

"To me, writing is allowing your mind to get quiet enough to be able to listen, because nobody knows where ideas come from, which is why writers are such a messed up group, as you well know. We don't know where it comes from. … The inspiring stuff usually comes when you are least expecting it."

And at some point early in that seven-day window, the magic, the melody of March Madness materialized with eight consecutive notes in his head:

Da-da-da-da DA da-da-da

Christianson says he was given two gifts related to his craft.

The first was being pushed into piano lessons by his father at age 5.

"Which is a great time for kids to start on music before they realize how hard it is," Christianson says. "I can't tell you the number of times I've tried to become a guitar player. 'Well, you know five fingers, you just have to turn around and put them in different places, how hard could it be?' Well, I was a total failure at becoming a guitar player both on acoustic and electric. It just didn't translate. So getting started at 5 years old was the best gift my father ever gave me."

His father was a piano player. He played in a big band in the 1920s and even got on a radio show, but he had to quit and help his father during the Great Depression. His mother played violin. Christianson's great-great grandfather paid his fare on the transatlantic voyage from England to the U.S. by playing accordion with the ship's band.

Christianson came from humble origins, growing up on what he says were "the wrong side of the tracks" in Yonkers, New York.

But what the apartment did have was a Winter's upright piano, about the height of a desk, pushed up against one wall.

"It was kind of a dumpy piano, but it was a piano," Christianson says. "That's the piano I learned on."

His father later tried to push him away from pursuing a musical career. "Which meant, of course, that I had to go into music," he says.

He earned his undergraduate degree upstate at SUNY Potsdam in the early 1970s and attended graduate school at the University of Michigan, where he'd become interested in the burgeoning music technology of synthesizers. He worked with early models like the VCS 3 and each new iteration.

When he first returned to New York City after college, Christianson was playing keyboards in Greenwich Village cabarets, a golden age for the clubs. His prowess was noticed one night by Broadway director Steve Reinhardt. He asked Christianson if he'd like to fill in on a musical, "The Magic Show," starring Doug Henning. The lead keyboardist, future David Letterman bandleader Paul Shaffer, was taking a month off to work on another project.

"There weren't a lot of (keyboard) players in New York that knew how to work with synths. I did, so I got a shot," Christianson says. "There weren't any (computer) programs. You had to come up with it on the spot by turning the dials."

He could write and arrange music, too. That along with keyboard and synthesizer expertise led to more and more work.

This is where his second gift came in.

"I was lucky enough to be in New York during the heyday of recording studios and recording live orchestras," Christianson says.

He'd write a piece of music at night and be in a studio at 10 a.m. the next morning conducting a live orchestra - sometimes small, sometimes large. It was then that he received another level of education from what he called some of the best musicians in the world.

"They are the ones who teach you," Christianson said. "I was always the least talented person in the room, but that was great because then I got to learn from people more talented than I was. It would be very boring if I was the smartest person in that. That was the greatest gift I've been given."

Keyboardists are notorious for working too quickly, for getting ahead of other members of the band, particularly the drummers.

"The drummers taught me how to not rush my groove," he says. "There are some incredibly great drummers in New York that you can literally - I don't mean this figuratively - that you can literally set your watch by. They beat me into submission. So now I have a good sense of timing and groove."

As the seven-day clock counted down on CBS's assignment in late 1992, he had an advantage that might seem counterintuitive: He had another constraint beyond the deadline.

He was working within a specific genre - sports themes - for which he'd already built some rules through prior experience. Without those constraints, too much time and freedom can lead to creative paralysis.

"It's easier to write when you don't have unlimited places you can go," he says. "There's only certain places you could go melody-wise or time-wise or groove-wise. That automatically limits your parameters."

He found with other successful sports themes he'd written that they share a characteristic: an underlying groove. The groove is the element of the song where "you feel your butt moving and you don't know why it's moving."

He developed what he calls "sports groove," which was essentially a mathematical formula.

"A triplet groove, in other words, three eighth notes to a single beat no matter what the tempo. That's sort of the sports groove," he said.

The groove typically is driven by drums. And when he thought about a particular NCAA tournament groove, he was inspired by the most common sound associated with the sport: dribbling a ball on a wooden court.

Early in the song, there are rapid intervals of dribble-like drums, akin to something like that of crossover dribbles - like Tim Hardaway's UTEP two-step of the late 1980s.

And the tempo should be fast. Groove can also be defined as "propulsive rhythm," and Christianson wanted there to be a sense of forward movement.

He began experimenting with different paces and dribble-like beats on his drum machine, the Linn 9000, which had 18 different drum sounds and a mixing console.

For his NHL theme, he flew to Buffalo to record ice-level sounds from warmups before a Sabres game: the sounds of blades cutting on the ice, pucks hitting the plexiglass, and sticks slapping the puck. They were subtly incorporated into the track.

But for the NCAA theme, he owned a library of recorded sports sounds and incorporated a basketball being dribbled into the rhythm, which one can hear woven in the original.

He had the groove, but it's the earworm melody he placed on top of it that separates it from other sports themes.

He knew the dribble should influence his theme. He knew the tempo should be fast. But he also knew there was an emotion he wanted to evoke.

He hadn't been much of an athlete, but he played sports as a kid. He also played trumpet and trombone in his high school marching band. He knew enough about basketball and the nature of the tournament. It's unlike any other playoff: the rare event where underdogs regularly succeed, where a No. 12 seed topples a No. 5 almost every year.

The sport was also more graceful than, say, hockey and football.

He experimented with da-da-da-da DA da-da-da expressed in electronic brass and woodwind synth sounds. He also made the unusual choice to play it in a major key, which isn't the domain of most sports themes.

"Think of a major key as happy, a minor key as not happy," Christianson says. "My NHL theme was written in a minor key, it comes across as a little more dangerous. Hockey is more in your face. Basketball is more … these guys are incredible athletes but they are light on their feet and can turn on a dime and it's more up, more positive. A major key kind of thing. That entered into it."

The synthetic brass sounds of da-da-da-da DA da-da-da were meant to bring you up, not down.

He even began the theme with an unusual opening that sounds like a cross between a pick scrape on an electric guitar and a laser being shot out of a "Star Wars" blaster. That initial jolt amps up the energy immediately.

"It was a white noise sound I made by turning dials on a Minimoog," he says.

Even for Christianson, it's hard to explain. It just sounded right. But that leads to another one of his secrets.

He's lucky to have a basement studio in the two-story Chelsea apartment where he and his wife have lived for more than 30 years. The soundproof, garden-level room allows him a great advantage other composers in the city don't enjoy: he can work at any hour without disturbing neighbors.

"The apartment my wife and I lived in before we moved to where we are now, it would be 8 p.m. at night and the lady underneath me would start hitting her ceiling with a broom," Christianson said. "I'd say 'Okaaayyyy,' and I had to shut it down."

He needed a space to be able to work at night with tight deadlines. And he learned much from working on commercials during those nights of tight turnarounds. He estimates he's scored about 2,000 commercials.

"Usually my first instinct turns out to be the right one. I've learned to trust that," he says. "Rather than sitting there and coming out with half a melody and going, 'Nah that sucks, let's try again,' you've got to stop editing yourself. That's what commercials taught me to do. Deadlines for commercials were just nuts."

He had another rule tied to simplicity when writing themes, too: "They should be simple - they shouldn't be, as I say, 'cute,' when you are arranging. It should be immediately accessible to whoever is listening to it."

He edited it all together and sent off his cassette tape.

After his song was selected, he went to a studio to conduct nine brass players in creating overdubs of the exact same notes from his original synthesizer samples. He then returned to his studio to mix the two sources together to create the brassy notes in the final version.

He had another tight deadline, a few additional days, to make a handful of versions of the theme, shorter ones, to play coming in and out of TV timeouts.

That spring, it debuted as the opening to the 1993 tournament selection show.

For college hoops fans, it became the tournament's soundtrack.

Different people have different reasons to explain why the composition became iconic. They can be both technical and emotional.

In a feature on the song for The New York Times in 2017 - Christianson got a kick out of appearing on the front page of the sports section - writer Zach Schonbrun spoke to University of Cincinnati music professor James Kellaris, who studies the influence of music on consumers.

"It is a diminutive masterpiece of auditory branding genius," Kellaris said.

I asked Oberlin College music theory professor Brian Alegant what he thought made the theme so popular.

"The tune is popular for a lot of reasons," Alegant wrote in an email. "Quick tempo … Bright, brassy timbre (tone color) and crisp percussive effects create a sense of sizzle and energy and drive. A repeated bass note creates a sense of stability to the shifting harmonies, which are extended over several measures while the melody arcs up and down."

Christianson says he's read some musical theorists explain what makes the tune work. They are likely correct, though he says his poorest grades in college always came in musical theory.

"Music doesn't start on paper," he says. "It starts in the brain or the fingers. Paper is only so you can play it again in case you don't remember it. I've yet to meet a composer who thinks of music theory when he's writing."

Christianson did commit the tune's notes to paper, "sloppily," on double-sided music sheets. He still possesses it, along with handwritten versions of his other sports themes. They're part of his sports theme "bible," five or six pieces of folded folio player that are Scotch-taped together and unfold like an accordion. He goes through them when writing a new theme to make sure he's not repeating himself.

Harold Bryant, an executive producer and vice president at CBS, leans into the emotional explanations.

"It brings you memories," Bryant says. "When I hear that theme, it brings me back to watching the great Syracuse teams and sitting in the dorm, or sitting with my dad. He's a big Georgetown fan. It reminds you of positive memories. It energizes you. It's a theme that gets you pumped up.

"I see (the branding power) when the theme song comes on, and I see heads turn up. They recognize it and know what it is."

CBS created an updated version in 2003 with a different composer and added other variants in recent years - Bryant says they might refresh it again in a few years - but in 30 years they've never deviated much from the underlying notes and groove. The royalties keep coming for Christianson, who is credited with 85% of the writing for the new versions.

They've tested other themes but the reaction is always the same.

"People go, 'No, no, no, we like the old theme.' It's a comfort," Bryant says. "The theme and musical enhancements are comforting to folks."

As popular as the tune is, as often as he's heard it on his own TV over the decades, Christianson didn't realize how much his tune resonated until he heard a host of the "CBS Morning Show" explain how much they liked the theme a few years ago.

He then stumbled upon how many YouTubers had downloaded it and various video clips associated with it. He read some of the comments, too.

"The first year of the greatest theme music there is among sports fans," one user wrote below the video of the original rendition from 1993.

"Fell in love with this while watching Syracuse make its run to the title game in 1996. The best rendition CBS has ever put forth," wrote another.

"The electric basketball shooting bolts into the gynamsium (sic) … you know what i'm taling (sic) about" wrote another. (CBS played up the laser sounds in a later version.)

Over time, as the song grew in popularity, Christianson has been asked to play it at holiday parties when a piano is present.

"I refuse," he says. "I tell them if they want to listen to it, turn on CBS and watch the game."

Will he be watching Thursday? He says he always does, particularly the final minutes of games.

He knows that he'll be most widely remembered for this tune, even if his peers hold other works in higher esteem, like "The Christmas Carol - The Concert," for which he was the composer and executive producer. He's conducted Broadway musicals and the "Saturday Night Live" band. But he's OK with the NCAA theme being his piece of work most likely to live on.

"The funny thing about being a writer," Christianson said, "is you never know which piece you write, in any genre, will be a hit."

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.