More than an athlete: How NBA players are building careers beyond basketball

It's the end of July in Akron, Ohio, and thousands of people have gathered to watch LeBron James take the stage in a suit and tie, looking more like a business mogul than one of the greatest basketball players in the history of the sport.

He's returned home to officially open his I Promise School, in partnership with Akron Public Schools, to educate and support at-risk kids in the area. Students will receive free uniforms, a free bike, and free breakfast, lunch, and snacks at school, and every student who graduates is guaranteed tuition to the University of Akron.

It's a proud moment that's been in the making for years; James started the I Promise program in 2011 and began his partnership with the university in 2015 by helping provide scholarships for more than 1,000 high school graduates.

Inside the Los Angeles office of Uninterrupted, the digital media company James co-founded, a giant neon sign reads: "I am more than an athlete." As he delivers a heartfelt 10-minute speech to the crowd, recalling his own experience growing up as an underprivileged kid with the fear of becoming a statistic, the Lakers megastar and three-time NBA champion is clearly living up to that statement.

James is the most visible example of how a professional basketball player can balance on-court stardom with off-court success, but he's hardly alone. An increasing number of players are enjoying second careers outside the arena, showing off their diverse skill sets and preparing for life after basketball.

Kelly Oubre Jr., aspiring designer

Growing up in the Eastover subdivision of New Orleans, Kelly Oubre Jr. made a name for himself with a bizarre array of sartorial choices. They helped shape the full-blown fashion icon that he is today, with his unbuttoned dress shirts, all-over-print sweaters, sleeveless blouses, thousand-dollar necklaces, prescription Cartier glasses, and leather bags.

"My dad always told me I looked homeless walking out the house," Oubre told theScore. "But I didn't care. I knew I looked fresh."

Oubre cites musician Lenny Kravitz as an early inspiration. Kravitz is also a style icon within his industry, best known for a range of signature items that include skinny leather pants, Chelsea boots, one-of-a-kind jewelry, and twin nipple rings.

"I wanted to be someone like that," Oubre said, "who could just capture the emotion of what he was feeling with an outfit."

After he was drafted by the Washington Wizards in 2015, Oubre set his sights on starting a high-end streetwear brand called Dope $oul.

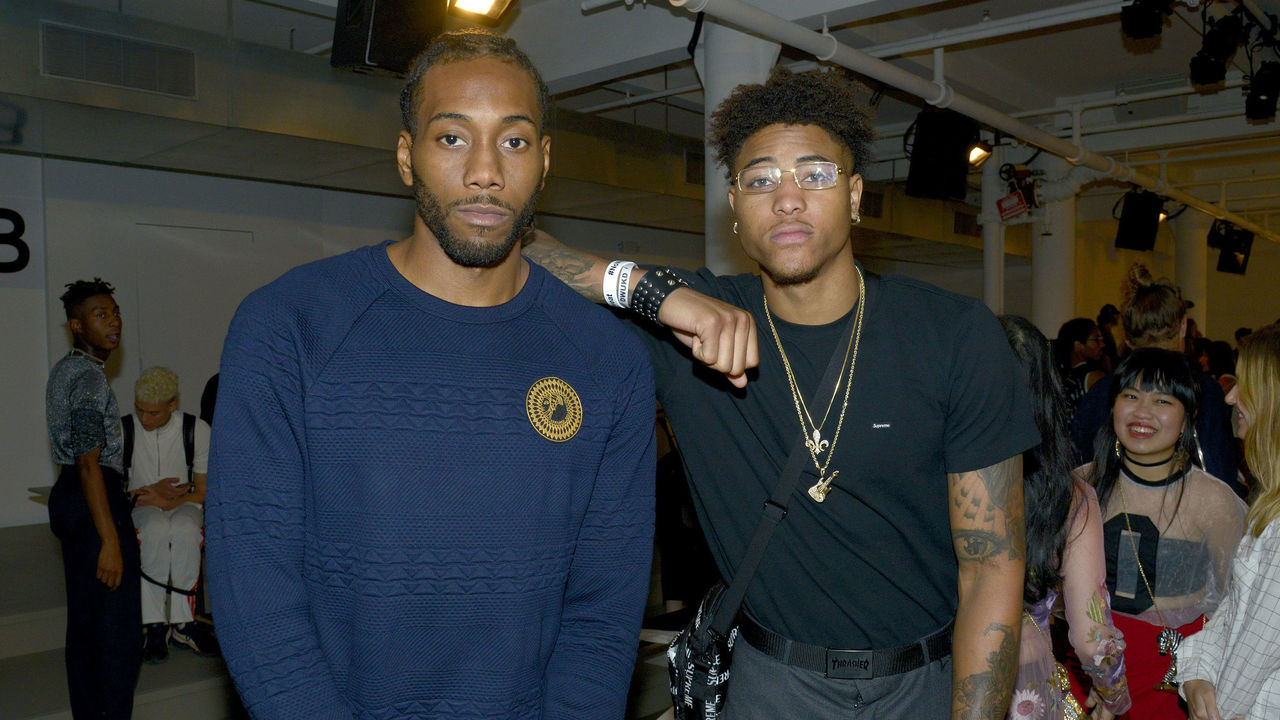

Oubre's pregame outfits, including statement pieces like a leopard-print faux-fur jacket and plaid trousers, drew the attention of designers. That secured him an invite to New York Fashion Week in summer 2016 after his rookie season.

Attending fashion week for the first time was exciting for Oubre, but also humbling - and enlightening. While players like James and Kawhi Leonard sat in the front row, Oubre had a low profile as a mostly unknown name in basketball and fashion circles. He saw that there was much more to being a designer than the glitz and glamor of a runway show, and he had a lot to learn if he wanted to start his own brand.

"I thought I was going to come in, throw some names on some shirts, put it online and sell it," said Oubre.

Oubre's been a New York Fashion Week fixture every year since and is using his access to pick the brains of prominent designers including Kanye West, Virgil Abloh, and Pharrell Williams. He's also spent the past few years studying different manufacturing processes and is building a business plan in order to finally launch his company.

Beyond making a dent in the fashion industry, Oubre hopes to help unite young people and inspire them to pursue their own creative paths. He intends to donate the eventual proceeds from his brand to an organization that will benefit the community.

While Oubre's provided glimpses of Dope $oul sample pieces on social media, many of his designs are still in his notebooks.

"It's all about fine-tuning," the Phoenix Suns small forward said. "I haven't really done much in fashion. I can never be complacent. I always want to grow and learn."

Blake Griffin, comic in the making

It's the first night of the 2016 Just For Laughs Festival in Montreal. "Sirius" - a 1982 instrumental by The Alan Parsons Project that became famous as the theme music of the '90s Chicago Bulls - blares as Blake Griffin steps on stage.

The then-Los Angeles Clippers power forward confidently grabs the mic and launches into a monologue about how he's sure everyone in the audience thinks he's stupid because they think all athletes are stupid. Griffin blames this perception on the postgame interview.

"I would love to see somebody considered smart by the real world get interviewed 30 seconds after they just finished exercising for two straight hours," Griffin says. "It's not that we're dumb. We just can't get enough oxygen to our brain."

To demonstrate his point, Griffin brings an audience member on stage and interviews him while he does jumping jacks and pushups.

The crowd roars with laughter.

Griffin receives positive reviews - and while he looks like a natural, the 10-minute set is the culmination of years of preparation.

Neal Brennan is the co-creator of "The Chappelle Show," a screenwriter for TV and movies, and a comedian. After he met Griffin at the 2014 ESPY Awards, the two became fast friends.

Brennan quickly sensed that Griffin wanted to do something more with his comedic chops. Whenever the two went out for dinner in Los Angeles, Griffin asked Brennan about the world of stand-up, awestruck that Brennan could just walk into any comedy club on a given evening and perform a set.

Griffin started writing his own jokes, making observations about the absurdity of being an NBA player. In particular, he found the postgame interview routine ridiculous. In what other occupation, he thought, would they shove a bunch of microphones in your face while you were half-naked just minutes after you finished two-plus hours of intense physical exercise?

But while the jokes piled up, Griffin had reservations.

"I wasn't sure if people would find any of it interesting," he told theScore.

Griffin's hesitation, in fact, was what convinced Brennan that the 2011 Slam Dunk contest champion could succeed in comedy. Brennan realized Griffin wasn't just another athlete who thought he could use his celebrity and status to get a few cheap laughs.

Brennan helped the forward reshape some of his punchlines, encouraged him to perform at a comedy club in Santa Monica, and offered him tips afterward.

"Stuff like 'don't finger the microphone cord' (during your performance), because that's what all amateurs do," Brennan told theScore.

Griffin's approach - finding a mentor in the industry, being open to constructive criticism, constantly refining his jokes, and attention to detail in general - earned him respect within the comedy scene.

"Every comedian that has seen him has said he's funny," Brennan said. "These are people that have nothing to gain from it. These people don't want his autograph, and they're haters by nature, and they're all like, 'Dude, he's actually funny.'"

Last December, Griffin held a comedy fundraiser for his Team Griffin Foundation, which encourages young people to pursue their passions. For his part, Griffin wants to pursue stand-up as a potential full-time career after he retires from basketball. Brennan thinks the Detroit Pistons star is wise to get started now, while he's still a recognizable face.

"(NBA players) are so valuable while they're still playing," Brennan said. "It's like ... the minute you drive a new car off the lot, it goes down in value. While it's on the lot, it is really valuable. These guys are on the lot right now."

Shaun Livingston and Andre Iguodala, investment gurus

Many NBA players may not have the connections or the chops for Hollywood, but a growing number are getting into something just as lucrative: business and investing.

When Shaun Livingston entered the NBA out of high school in 2004, there was no one in his circle to teach him how to deal with becoming a millionaire overnight.

"People take advantage of what you don't know," Livingston told theScore.

Today, Livingston regularly watches CNBC and reads the MarketWatch website for financial news. He's also taken a particular interest in commercial real estate. At this stage of his career, Livingston calls himself a conservative investor and is still looking for the right opportunities.

"I wouldn't say I'm a shark," Livingston said. "But I'm intuitive about how I want to eventually diversify my portfolio."

Now 33, Livingston's mentored younger players on how to spend their money.

"Don't be a follower," Livingston said. "Just because a guy you see is buying a fancy Mercedes Benz ... it might be because he's been in the league 10 years and made $50 million, and you're on a rookie salary. You just have to think about that and build good habits."

Experience is the best teacher, as Livingston would attest, but many players around the league are now seeking help from professionals. Paul Millsap, Kyrie Irving, and Spencer Dinwiddie, among others, attended a Harvard Business School course called "Crossover into Business" last summer. Sitting alongside MBA students, players learned about the intricacies of the business world and how they could also become entrepreneurs.

One of the course's case studies: James and his burgeoning business empire.

"(LeBron) is so public about what he's doing," Millsap told theScore. "It makes sense to follow what he's doing, and to try and get more knowledge about how he's made it and how he did what he did."

While Harvard Business School helps in that regard, the Golden State Warriors' locker room has become a hub of business savvy in its own right - and not just because of Livingston's growing portfolio.

Andre Iguodala, 34, joined the team five years ago. Early in his career, the forward started talking to Ivy League graduates he knew and kept asking questions about business. Iguodala was an investor before he headed to Oakland, putting money into companies like Facebook, Twitter, and Tesla.

In his time with the Warriors, Iguodala's become a prominent presence as an investor in Silicon Valley. He's connected with some of the top executives in the tech sector and sat in on meetings.

"The first few meetings, I would just sit back and listen," Iguodala told theScore. "I didn't grow up like the majority of them, so it was a challenge to figure it all out. Every meeting, I would pick up something. That's what I try to preach to other people. You just have to seek it."

Iguodala reads tech newsletters daily and pores over financial statements and annual reports the way most players study postgame stat sheets. He and Steph Curry hosted the first NBA Players' Technology Summit in 2017. This year, Kevin Durant joined Iguodala as the event's co-host. Iguodala says he only watches two television channels: Bloomberg and The Golf Channel (plus basketball, which he calls "work").

Iguodala says his peers frequently contact him for investment tips, and he's focused on relaying his knowledge to younger players. He and Warriors owner Joe Lacob recently met with the team to discuss the nuances of finances and investing.

"Once you master something," Iguodala said, "it's your duty to pass it on."

He added, "We don't get the financial education to understand the ins and outs about taxes, about assets versus liabilities. That's the issue we've always had in the African-American community. These are simple things but we don't have access to that knowledge because we don't have that structure and the system isn't set up for us to succeed, especially in America. So we're always overcoming the odds."

David West, COO

David West retired last summer after 15 years in the NBA - the last two with Golden State. Having spent time around Iguodala and Livingston, he came away with a key lesson.

"It's important to pick up skills that are transferable once you're finished playing," West told theScore. "That's the most important kind of investment you can make."

In retirement, West was looking forward to spending time with his kids, catching up on some reading, and not being tied to a daily work schedule - though he'd spent much of his playing career learning how businesses are run. But a conversation with Historic Basketball League co-founder Ricky Volante about the HBL's initiative to provide collegiate athletes with both compensation and education swayed West, and he accepted the role of league COO in November.

Now, West spends most of his day helping set up the HBL's structure so it will be running by 2020.

"The kids need another option," West said. "I feel like this could be that option."

Livingston applauds West for working to make a difference for the next generation of basketball players.

"We have more of a platform now," Livingston said. "We can be our own CEOs."

At least a couple of Livingston's teammates are also breaking down barriers in other industries while giving back to their communities. Durant's charitable foundation recently committed $10 million to help disadvantaged students in Prince George's County, Md., finish college, and Draymond Green is opening 20 low-cost gyms in Michigan and Illinois. Scratching the surface of what players are doing elsewhere in the league, Chris Paul's production company produced the film "Crossroads" about a lacrosse team comprised of at-risk teens; Russell Westbrook's clothing line Honor The Gift launched a second collection with an inner-city theme; and Dwyane Wade donated $200,000 to the March for Our Lives fundraiser to support students taking action against gun violence after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School.

As he has been throughout most of his NBA career, James is at the epicenter of it all, his combination of philanthropy and business sense providing a perfect example of how to be so much more than an athlete.

"There's a stigma that comes with being a basketball player," Iguodala said. "I want to step outside of how a typical basketball player is perceived by people."