How sports became 'an American obsession' 100 years ago

Baseball had yet to tar Shoeless Joe Jackson as a cheat when the sweet-swinging outfielder, one of eight Chicago White Sox players alleged to have thrown the World Series in 1919, stepped to bat at Manhattan's Polo Grounds the following July 19. Rain clouds that delayed the start of a doubleheader with the New York Yankees were gone by the second game's second inning, when Jackson, his club chasing the home team in the American League pennant hunt, connected on a deep drive that soared over the right-field wall.

Characteristic of the sport's dead-ball era, Jackson wasn't much of a slugger: The most home runs he ever hit, 12, came in 1920, his final season in the majors. Across Jackson's 13-year career, the average team stroked a homer once every five games, at most, manufacturing offense instead through light contact, bunts, and basepath speed. Power was subordinate to moxie and guile. That damp summer afternoon, though, signaled change was coming.

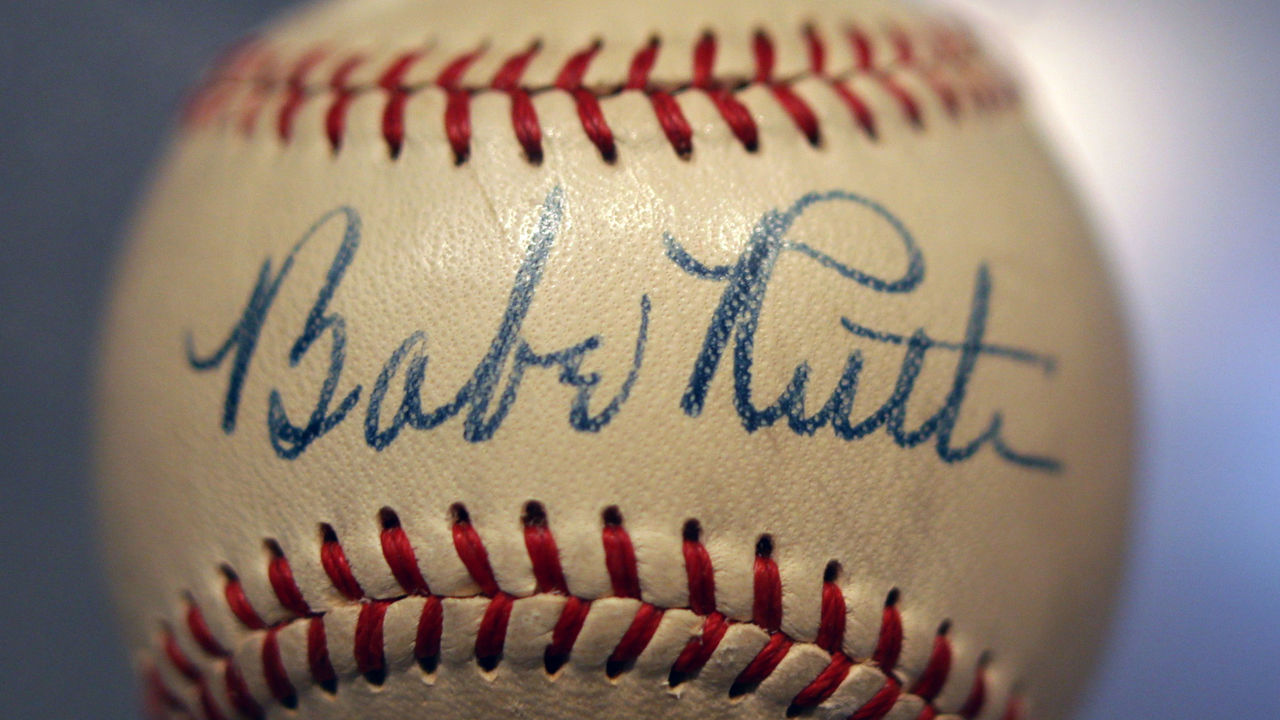

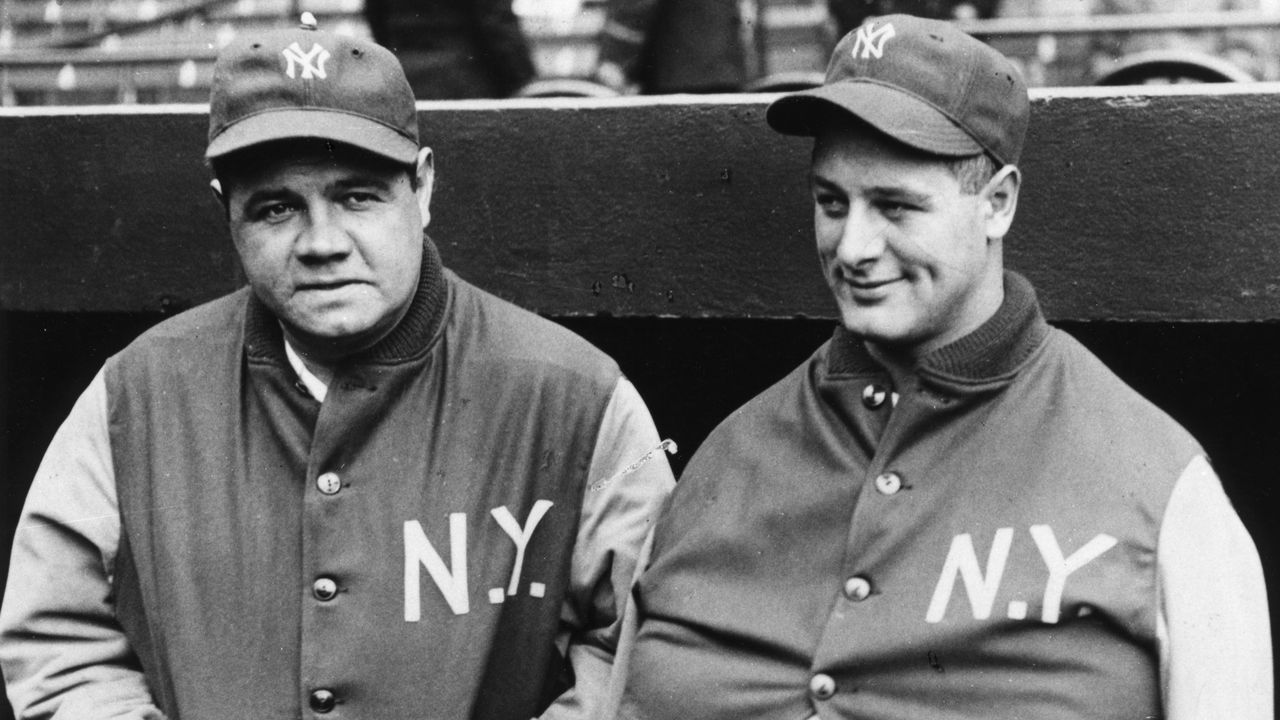

1920 was Babe Ruth's first season in Yankee pinstripes, the Boston Red Sox having flipped him to their budding archrival that January for cash. The Bambino tagged 29 home runs for Boston his last year there, a big-league record, and in New York, he immediately began to rake like no batter before him. Entering the White Sox twin bill, a mere 86 games into the campaign, Ruth was sitting on 29 homers, rapping once again on history's door.

More than Ruth's Yankees debut, 1920 was baseball's first full-length season since the end of the Great War, and it coincided with the tail end of a flu pandemic that killed, at minimum, 50 million people worldwide. Americans coveted normalcy, and in New York, they yearned for Ruth to crank moonshots, deeper and more frequently than ever.

The breakthrough came shortly after Jackson went yard, in the bottom of the fourth on July 19. Chicago still led 1-0 when southpaw Dickey Kerr, battling Ruth in a 2-2 count, tried to fool the Yankees' cleanup hitter with a curveball.

"There was a resounding smack as bat met ball and the noise from the stand swelled in volume before the ball had started its descent," The New York Times reported from the park, recounting how the 28,000 fans on hand greeted Ruth's blast with deafening applause. The shot to right field was Ruth's 30th homer, and by season's end, his count totaled 54, a new standard for greatness that he'd surpass twice more before the decade was out.

In hindsight, the timing was perfect. Sent to New York at the dawn of the 1920s, a human remedy to the Black Sox misdeeds, Ruth came to define the free-swinging spirit of the age. War and contagion were bygone memories in the Roaring Twenties, when pay increases and shortened workweeks unlocked leisure time in the U.S., and people searched for fun diversions to fill the hours.

This was the decade, the historian Frederick Lewis Allen once observed, when sports became "an American obsession."

As our own pandemic year ends, to think back a century is to remember how baseball - and football, boxing, tennis, and golf - first gripped the United States' collective attention. Highlights aired weekly at movie theaters. Starting in 1921, radio broadcasts connected listeners across the nation to faraway title games and marquee fights. For daily news, the public turned to newspapers, whose sportswriters had leeway to relentlessly hype the athletes they covered.

Ruth was the Sultan of Swat, the Wizard of Wallop, the embodiment of this boom time, and as author Michael K. Bohn has written, almost everybody loved the guy: "He appealed to everyone but opposing pitchers." Bohn made this remark in his 2009 book, "Heroes & Ballyhoo," the latter term synonymous with the buzz that surrounded sports in the '20s. Ballyhoo was a phenomenon that fed itself, Bohn wrote. Journalists promoted the players, which drew spectators to games, and eventually, their interest compelled promoters and teams to shell out to build grand new venues. All the while, fans demanded more coverage of their favorite athletes, whose reputations thrived.

"And on it went," Bohn wrote.

If two symbols defined the decade in sports, they were probably the knockout and the home run, like Ruth's record-breaker against Chicago that inspired the Polo Grounds faithful to fling their hats, wave their arms, and howl "in glee," as the Times noted. The Yankees didn't win the AL pennant in 1920, but their heyday wasn't far off, and throughout that period, they spearheaded an offensive revolution. By the end of the '20s, the average MLB team clubbed a homer every couple of games, and the Yanks and select other contenders were almost twice as dangerous.

The fans who flocked to watch Ruth live appreciated his power, but also his fondness for drinking and aversion to team-imposed curfews, Donald L. Miller wrote in The Conversation several years ago: "White-collar workers fearful of flouting authority and telling off their bosses could take secret pleasure in Ruth’s insubordination." Whatever their particular motivation, these diehards helped the Yankees smash spectatorship records in the early '20s, spurring owner Jacob Ruppert to commission a bigger ballpark in the Bronx. The original Yankee Stadium opened for play in April 1923, less than a year after construction started.

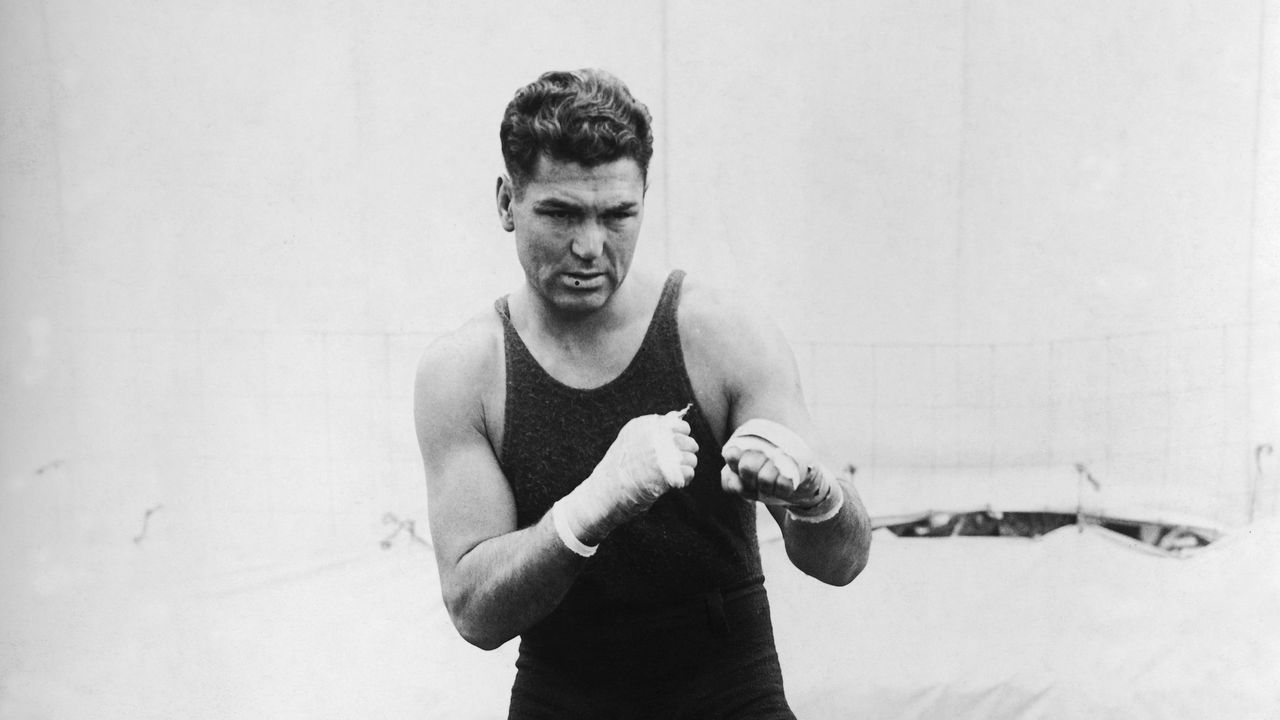

Across town from Ruppert's baseball temple, promoter Tex Rickard soon broke ground on Madison Square Garden, New York's regal new hub for basketball, hockey, and boxing. Rickard understood the power of spectacle, and together with Jack Dempsey, the era's best heavyweight, he organized mammoth title bouts at MSG and stadiums around the U.S. that in some cases drew more than 100,000 spectators.

Dempsey was boxing's original moneymaker, the power puncher who legitimized the brutal art for mass consumption. The first sporting event broadcast on radio nationwide was his July 2, 1921 title defense against French war pilot Georges Carpentier, which also generated boxing's first million-dollar gate. A suspected but acquitted draft dodger, Dempsey entered the ring in New Jersey a foil to his distinguished challenger, but he won over the capacity crowd of 91,613 by KO'ing Carpentier in the fourth round. In 1927, 50 million listeners worldwide heard Dempsey fight Gene Tunney, and this time, the gate at Chicago's Soldier Field surpassed $2 million.

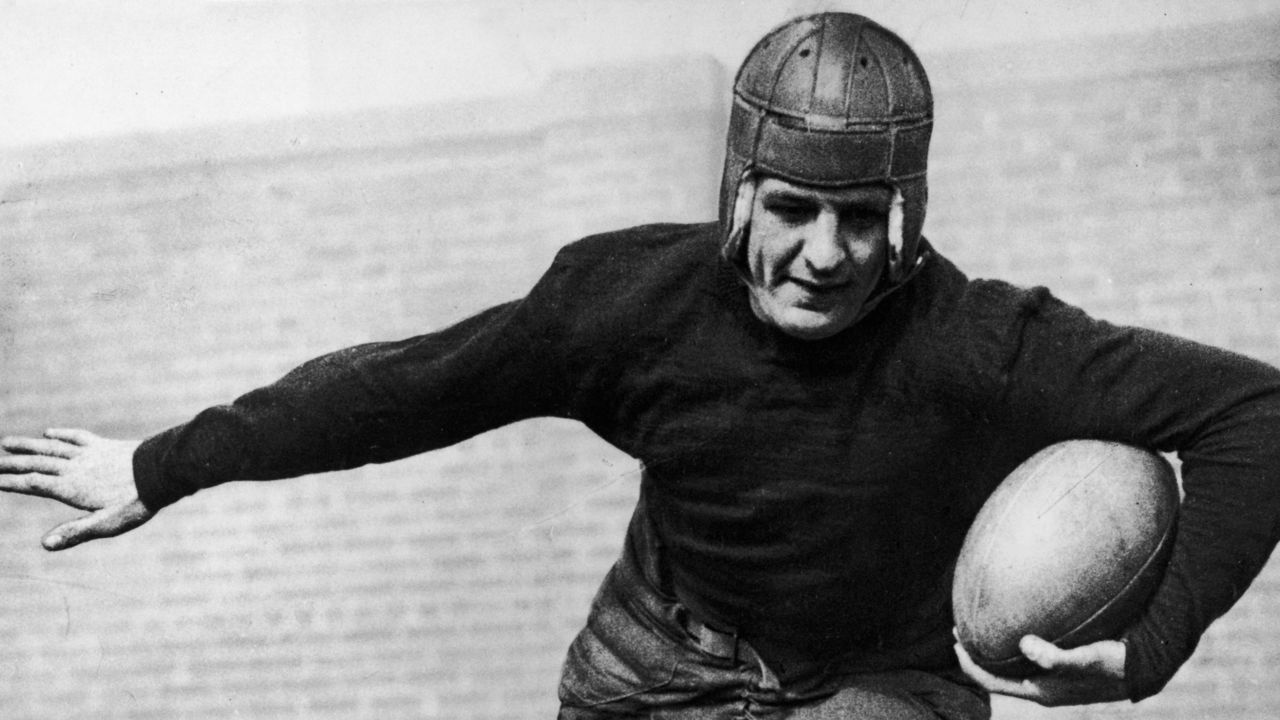

Around the same time, football's main superstars were Notre Dame coach Knute Rockne and Illinois halfback Red Grange, and Grantland Rice was there to mythologize them.

Rice was the 1920s' foremost celebrity sportswriter, an audacious wordsmith whose columns were published nationally and who, Miller notes, was paid better than Ruth and President Calvin Coolidge. With the NFL in its infancy, college football was the biggest game around. Rockne's Fighting Irish squads pioneered the forward pass; Grange, nicknamed the "Galloping Ghost," was a consensus All-American three years running; and Rice's fawning prose related to millions of readers their greatest feats.

Consider the events of Oct. 18, 1924, when Notre Dame beat rival Army 13-7 at the Polo Grounds and Rice invoked scripture to describe Rockne's star backfield quartet: "Outlined against a blue-gray October sky the Four Horsemen rode again. In dramatic lore they are known as famine, pestilence, destruction and death. These are only aliases. Their real names are: Stuhldreher, Miller, Crowley and Layden."

That day in Illinois, Grange rushed and passed for 402 yards and scored five touchdowns against mighty Michigan, with whom the Fighting Illini had split the national championship in 1923. Stirred by the display, Rice later turned to poetry to illustrate Grange's evasiveness on the gridiron:

A streak of fire, a breath of flame

Eluding all who reach and clutch;

A gray ghost thrown into the game

That rival hands may never touch;

A rubber bounding, blasting soul

Whose destination is the goal.

Plenty of other sports spiked in popularity across the '20s, each thanks in large part to the exploits of a fabled figure.

In horse racing, that was Man o' War, the stallion who won all 11 races he entered as a 3-year-old in 1920, including the Preakness Stakes and Belmont Stakes. (Naturally, the only horse ever to beat Man o' War was named Upset.) In golf and tennis, respectively, Bobby Jones and Bill Tilden hoarded major titles and became their games' first fan favorites. (Jones' handiwork endures today: He helped design Augusta National and founded the Masters in 1934.) The era's best swimmer was Johnny Weissmuller, a five-time Olympic medalist who went on to star as Tarzan in a dozen films. (No 100-meter freestyler swam the race in under a minute before Weissmuller in 1922.)

Suffragettes won women the right to vote in 1920, and while flappers agitated for greater independence, top women athletes dazzled at home and on the global stage. Tennis legend Helen Wills won 11 of her 19 Grand Slam titles in the '20s, plus singles and doubles gold medals at the Paris Olympics in 1924. Gertrude Ederle earned three freestyle swimming medals at Paris, and on Aug. 6, 1926, the Manhattan native became the first woman to swim across the English Channel, in a tidy 14 hours, 31 minutes at that. No man had completed the crossing in fewer than 16 hours, much longer than it took Ederle to race from Cap Gris-Nez, France, to Kingsdown in choppy seas.

In different stories that month, The New York Times called Ederle a "superwoman" and the "Queen of Swimmers." On Aug. 27, upon her return to New York by boat from Europe, 2 million people turned out to fete Ederle via ticker-tape parade. The throng stretched from City Hall, by the Manhattan harborfront, five miles north to her home near Central Park.

"No president or king, soldier or statesman," the Times wrote in a front-page story the next day, "has ever enjoyed such an enthusiastic and affectionate outburst of acclaim by the metropolis." Ederle's parade, the phrasing implied, upstaged even the city's heartiest celebrations of Babe Ruth.

"Of course," Arthur Ashe once wrote about the 1920s, "it should have been more appropriately called the 'Golden Decade of (White) Sports,' for Black athletes were shut out of major-league baseball, eased out of professional football and basketball leagues, barred from Forest Hills in tennis, and unlawfully kept out of contention for the heavyweight boxing crown."

When Americans fell for sports, racial segregation was a societal norm, and it restricted Black athletes from the national spotlight. Following Jack Johnson's reign as heavyweight champ, from 1908-15, no Black boxer got to vie for the belt until Joe Louis in 1937. Jackie Robinson didn't break the MLB color barrier until 1947. Only in 1956 did Althea Gibson become tennis' first Black major champion, followed by Ashe himself on the men's side in 1968.

Progress was halting, but even in the '20s, Ashe noted in his 1988 book, "A Hard Road to Glory: A History of the African American Athlete," Black sports stars made significant advances. At the Paris Olympics, where Weissmuller, Wills, and Ederle all excelled, American long jumper DeHart Hubbard won gold in his event, laying the groundwork for Jesse Owens' four-gold breakout at Berlin in 1936. The creation of the barnstorming, all-Black Harlem Globetrotters and New York Renaissance helped professionalize basketball, and in 1925, the Rens beat the Original Celtics, the era's dominant team, for the title of world champion.

Baseball's Negro Leagues were experiencing their own moment. Starting in the 1920s, Black leagues launched the Hall of Fame careers of Satchel Paige, Martin Dihigo, Judy Johnson, and Cool Papa Bell, plus those of more legends whose star turns and struggle preceded Robinson's MLB debut. Teams found footholds in Chicago and Detroit, in Kansas City and St. Louis, and for four years in the mid-'20s, the champs of two top circuits met each October to contest the Negro World Series.

During that same span, the New York Yankees transformed into a force. On Opening Day at Yankee Stadium in 1923, Ruth christened the park with a three-run homer to right, this time against the Red Sox and before a crowd that exceeded 70,000. The franchise won its first World Series that October, and the Murderers' Row core - Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Bob Meusel, Tony Lazzeri - led New York to two more titles in 1927 and 1928. Ruth knocked 60 homers in '27, a record that stood the rest of his life.

The decade didn't start with the Yankees appearing in the World Series, and it didn't conclude on that familiar note, either. On Sept. 18, 1929, Cleveland's baseball team took the field at Yankee Stadium in a dejected Bronx and changing America. The second-place Yanks had just fallen out of contention for the AL pennant. The stock market was about to plummet, shattering the decade to come, and Miller Huggins, New York's manager for the past 11 seasons, was days away from checking into hospital with influenza, which killed him before the end of September.

Twelve games remained to be played after Sept. 18, and Ruth didn't clear the fence in any of them, a rare reprieve for opposing AL pitchers. That day against Cleveland, across both games of the midweek doubleheader, New York got to savor one last taste of the '20s, the Times wrote: "The howitzers of the Yankees' greatest days, the Babe himself and Gehrig and Lazzeri, fired home runs in their very best fashion at the Stadium."

Within a few years, the Great Depression put a quarter of Americans out of work, and baseball attendance, an expendable luxury, cratered in turn. Yet many of the gains sports made in the '20s proved sustainable. Stadiums built in the '20s remain in use across a couple dozen major college campuses. Fans in 2020 await the return of the stadium experience, but beaming games into our homes is an entertainment staple.

By the following decade, a lesson of the 1920s seemed to be ingrained in the American psyche: Games can lift spirits. What historian Kevin Grace once told the Westchester Journal News about sports in the '30s was still true this summer: "For 60 minutes or three hours, the world was right again."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.