'Chasing the dream': So you want to work in baseball?

NASHVILLE - For a few days each December, in the hotel lobby where MLB's winter meetings are held, one group stands out for its appearance, youth, and emotion.

Baseball's insiders are generally outfitted in khakis and quarter-zip pullovers. This other group is wearing blazers that might be a bit too long in the sleeves and too wide in the shoulders, and the vibe is a mixture of fear and eagerness. They're generally college students or recent graduates looking for a foothold in the world of professional baseball.

Earlier in December, they wandered around the sprawling Gaylord Opryland Resort & Convention Center trying to land that first internship or job.

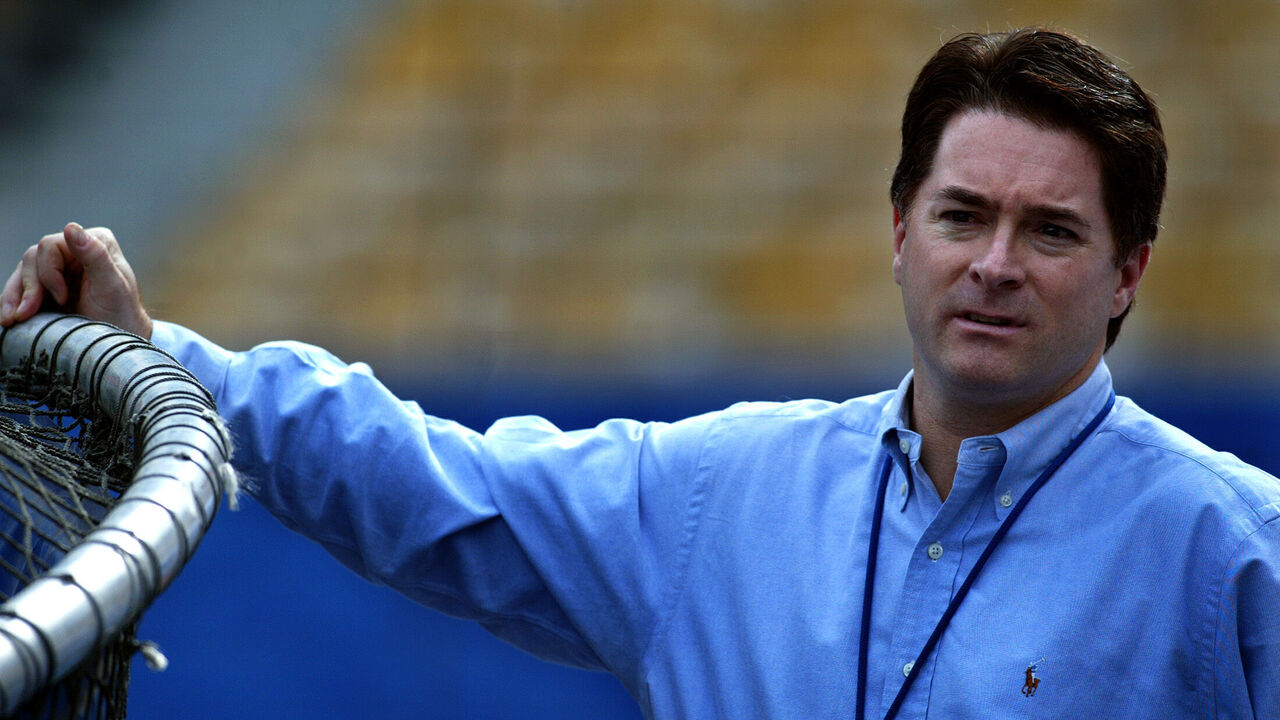

At the end of the first full day on Dec. 5, former Los Angeles Dodgers general manager and longtime executive Dan Evans noticed some of these hopefuls hugging a railing near the Falls Bar & Lounge, a busy foot-traffic area in the resort. They were interacting with each other, not reaching out to those they needed to connect with.

Evans is an instructor for Sports Management Worldwide, a training organization that boasts more than 400 alumni in roles with MLB clubs. The organization offers courses and holds an annual conference at the winter meetings, which many of these hopefuls are attending.

Evans knew some of them personally and could ID others in the program via their telltale lanyards. He knew the timid body language; it reminded him of those clinging to the edge of the pool back in his days as a summer lifeguard in Chicago.

In the dim nighttime light - Opryland's glass ceiling creates an outdoor feel indoors - Evans did what he always does when he comes across such a tentative group: herds them together and tries to stoke a little courage.

"Are you feeling fear?" he asked the dozen or so gathered around.

Some heads nod, illuminated by the park-like lanterns overhead.

Evans knows the winter meetings can overwhelm newcomers. The entire baseball industry is under this roof. He reminds them that everyone working in the industry felt that fear when they took their first steps.

"For some of them, it becomes paralyzing," Evans said later. "One thing I try to do is diffuse it and confront it. They are thinking, 'How am I in the same room as so and so? How am I doing this?' At some point, you have to overcome that.

"I try to introduce them to as many people walking by that are good people, people like (Washington Nationals GM) Mike Rizzo, people who remember their roots. You cannot take all the anxiety away. Part of the process is you have to face it, and meet it head on."

He wants to place them in a little better position to make their elevator pitches. If there's too much fear when those opportunities arise, Evans says they "cannot articulate" their skills, interests, and passion.

After he introduced one small group to Rizzo later in the evening, Rizzo began to engage them. A conversation began.

"And then I magically walk away," Evans said.

This is what first steps look like for many who go on to work in the game's front offices, coaching staffs, and broadcast booths. The hopeful job seekers compete to gain a foothold in a competitive industry where low-paying, entry-level positions attract hundreds of candidates. Many have advanced degrees and could make more money in another field, but analyzing widget sales isn't quite the draw that working in baseball is.

So, you want to work in baseball? We spent time with these job seekers in December to observe what they see, hear, and say as they weigh the opportunity - and cost - of chasing a dream.

'You have to love it'

A few hours earlier, in the indoor courtyard at another hotel, the hopeful job seekers settled in for the next panel at the Sports Management Worldwide conference.

They're here at their own expense, and it's cheaper to stay at The Inn at Opryland - situated next to a Cracker Barrel - than at the sprawling Opryland resort complex on the other side of McGavock Pike.

The space quiets as Dodgers manager Dave Roberts arrives and walks on stage. Roberts agreed to volunteer an hour of his time, as all the panelists do. It's an effort to give back, Evans said.

Roberts looked out upon five rows of mostly young faces, a crowd just shy of 200 hoping to work in baseball.

He shared details of his entry into the game, including the net sum from his first pro paycheck. "It was $344," he said.

Roberts was selected in the 28th round of the 1994 draft by the Detroit Tigers after starring at UCLA. His signing bonus was $1,000, pre-tax.

Roberts told the young faces they have to be resilient if they want to rise in this industry. Roberts is nothing if not irrepressible. He's a cancer survivor (Non-Hodgkins lymphoma), and the son of a U.S. Marine, which meant Roberts spent his childhood moving around to different military bases. He shared how he didn't reach the majors until 1999 as a 27-year-old with Cleveland.

"It's not always easy. It's a grind," Roberts said. "You get knocked down and then how do you respond?"

His love of the game helped him persevere. Evans, back in his capacity as Dodgers GM, brought Roberts to L.A. in December 2001 via trade. The 2002 season was Roberts' first chance to play regularly.

As the panel wrapped up, Evans turned to Roberts and said these hopefuls would be "unleashed" in the Opryland lobby that evening.

"Good luck," Roberts said. "That you're here, it speaks to you guys caring, being proactive. It's not easy to get in a car or plane. Impress upon people, let them know how much you love the game."

Even in this data age, Roberts said it's "still about people."

As Roberts departed, the job seekers rose from their chairs and mingled during the break. The lunch buffet would begin soon.

They come from all over

Micaiah DeWitt is a recent grad with a business degree from Lee University in Cleveland, Tennessee. He's currently selling cars at Integrity Chevy in Chattanooga, a couple of hours south down Interstate 23. Auto sales isn't his dream; he loves baseball and can handle a spreadsheet. He played at the NAIA level and even helped coach locally at the high school level. He's tall and lean like a former athlete, and wearing a dark suit.

A few weeks ago while browsing MLB.com, he saw an ad for this event and decided he couldn't pass it up.

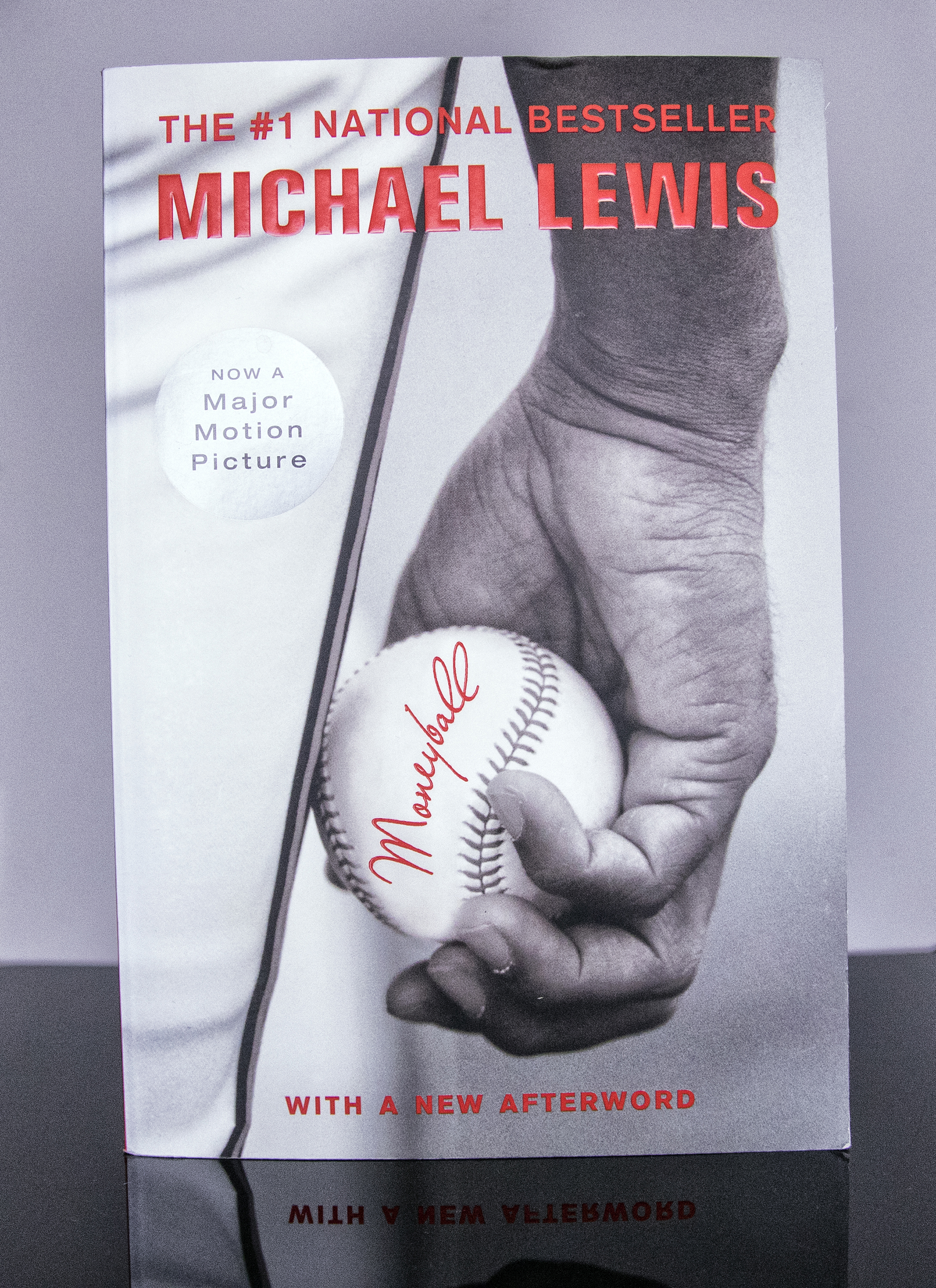

"It's funny you brought up 'Moneyball' - that's my favorite movie," DeWitt said.

While it helps to have an Ivy League degree and connections, part of the mission of Sports Management Worldwide is to democratize paths into the game.

"It's a tough barrier to entry. I've definitely seen that," DeWitt said. "The people that do get in, it's a dream job. Everyone loves it."

Weston Clare is a San Francisco-area native and student at Ole Miss. He started college this fall and has a LinkedIn page where he already describes himself as a "baseball expert."

He's a marketing major, adept with numbers, and is also attempting to secure a role as a student manager on the Ole Miss baseball team.

A few weeks ago he Googled "winter meetings" and an ad for this event appeared. He made the four-hour drive from campus. Many arrive here with no connections.

I asked him if he felt he loved the game enough, if he met Roberts' suggested prerequisite for making it a career. He articulated a sober view.

"The further in the future you go, you're going to have to love this game more and more to be part of it," he said.

He's interested in scouting, possibly becoming an agent, or even working in media. He's not sure.

"I'm just trying to see what I want to be," he said.

It's a tough thing to know at 19. But the next panel explains that it can be a big edge if you do, if you're one of the lucky ones.

Having the passion

Evans introduces the next group of speakers - scouts in the game - with a story.

It was back in the 1980s at Comiskey Park, when Evans was working as an assistant in the White Sox front office. This was before the internet, of course, and he was interested in a hobbyist evaluator who kept sending him a newsletter that offered thoughts on various professional players and their potential.

Evans thought the work was very good, so he asked Kevin Goldstein to come in for a visit.

As they met in Evans' cramped office, concessions workers were rolling kegs of beer in the upper-deck concourse above them. The metallic sounds shook the room. Evans remembers that detail along with Goldstein's enthusiasm for scouting.

"People notice passion," Evans said.

Although Goldstein didn't get a job with the White Sox, he went on to write for Baseball America and Baseball Prospectus. Later, he entered the pros as a scout for the Astros and now the Twins.

If Goldstein had any advantage, it was that he had a narrow interest: scouting.

"Don't tell me you'll do anything," Goldstein told the crowd. Find a focus, a niche.

Before arriving for the conference, Nathaniel Rodriguez had never traveled on his own. But he has the passion.

"I hopped on a plane from L.A., and it's really just about chasing a dream," Rodriguez said. "I believe all of us grow up with a dream, and it takes courage to chase it. This is my first step."

Rodriguez owns the advantage of knowing exactly what he wants to do.

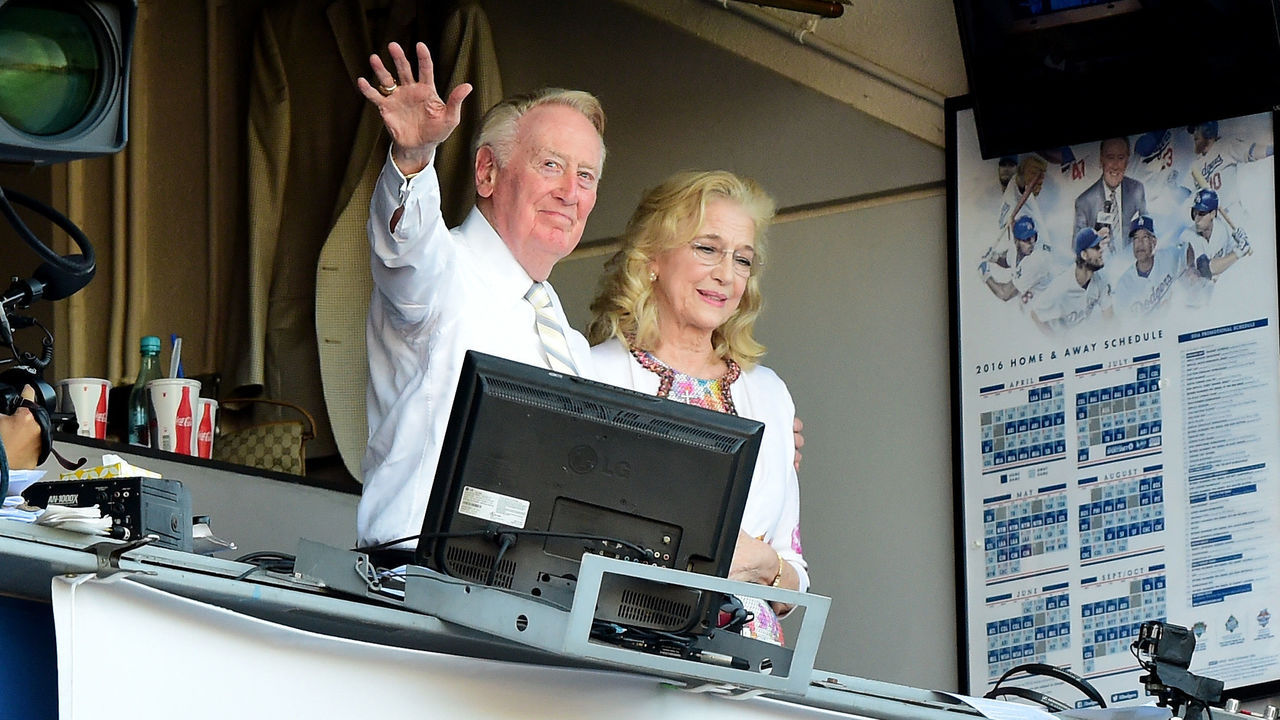

There are all types of jobs in baseball - not everyone attending wants to work in a front office - and Rodriguez wants to secure one of the rarest: to work as a play-by-play voice. He was inspired by watching countless Dodgers games.

"To have that voice in your house three hours a night, it almost gives you a role model," he said of the late Vin Scully.

He's begun honing his skills, calling live events - volleyball, baseball, and basketball games - at the University of La Verne out in eastern L.A. County.

His voice is rich and smooth. His shirt is complete with gold cufflinks. Again: he knows what he wants to do. But one thing that struck him in leaving his small world of La Verne is how many people are chasing the same dream.

"I think the competition is definitely next level," Rodriguez said. "As a 23-year-old myself, to come in here and try and stay focused on your own lane and not peek over (at) what the other person is trying to do, it's certainly a challenge."

He built up the courage to approach the MLB Network set at the Opryland a day earlier, and waited for host Greg Amsinger to end his show. He was nervous but approached him and extended his hand.

"He said worry about the bills later, chase your passion now," Rodriguez said. "Hearing that from a guy I look up to, who I would like to be one day, it's perfect advice."

The bar is high

Orioles assistant GM Sig Mejdal was one of the job seekers roaming the winter meetings lobby in New Orleans in 2003.

He'd bought a Baseball America handbook, cut out mugshots of various executives he was hoping to meet, and attached them to several pieces of paper so he could ID them in the lobby.

Earlier that year, he was studying sleep patterns for NASA when "Moneyball" - the book - arrived shortly after its release at his small apartment in Sunnyvale, California. He was off that day, so he started reading, and finished the book in the early hours of the morning.

"I read the line about how (Paul) DePodesta was not supposed to be there. That just got me excited," Mejdal told theScore last year. "'Holy shit, the A's hired someone like me!'"

He decided to travel to the winter meetings that winter.

The greatest lasting impact of "Moneyball" - book or movie - isn't the market inefficiencies it identified; rather, it changed the perception of who could work in a front office.

The trip worked out for Mejdal. His resume ended up on the desk of Jeffrey Luhnow, who met with him at the 2004 winter meetings and gave him his first job with the St. Louis Cardinals.

Dreams do come true in the lobby.

Evans remembers Trey Rose, the Pittsburgh Pirates' assistant director of baseball operations, who roamed the lobby as a college kid after taking the Sports Management Worldwide scouting course in 2016.

Elvis Martinez is another alumnus, and now the manager of communications for the Tampa Bay Rays. He got his start by passing out resumes in the hotel lobby. Evans received one, was impressed, and passed it along. A career began.

There are countless stories like these.

While "Moneyball" changed who worked in front offices, it also grew the number of job seekers exponentially. There are more jobs than there used to be, but the number of applicants dwarfs the number of openings. The bar is now even higher in terms of technical skills and competition.

"I've thought about how much harder it is now, as a junior person, to get in," Minnesota Twins GM Derek Falvey said.

While there are more front-office jobs, it's also more difficult to get your voice heard by decision-makers.

"To make an impact as the group gets bigger, the access to the higher level of baseball operations is a little less," Falvey said. "We try to keep it small enough so that (entry-level staffers) are getting face time with some of our most senior leaders, and are exposed to some of the key decisions that are being made. But it's changed, for sure.

"Squeezing that extra 1% out of certain areas has gotten harder. But there are also a lot of avenues for new data that we didn't have 10 years ago," Falvey said, noting new roles baseball has adopted in biomechanical data and technology in player development.

However, even for those who get inside the gates, the dream doesn't always turn out as imagined.

Dream vs. reality

Ethan Moore began chasing his dream job in high school.

He read "Moneyball" and several other analytical-based baseball books and was excited there was an opportunity for those who loved the game but hadn't played at high levels. He was strong in math and began mapping out a career plan.

He studied what data science skills he needed to make him an attractive candidate: data analytics, data visualization, machine learning, and statistical communication. He focused on acquiring them at Cal Poly, where he majored in statistics.

He gained real-world experience there, too, as the data analytics and video coordinator for the school's baseball team. He shared his research on social media and networked with team employees.

He had a clear dream and worked toward it.

"I wanted to work for the Rockies and help bring a World Series to Denver," he said of his hometown team.

Shortly after graduating, he landed an internship with the Twins. He was immediately met with some culture shock.

"Because these organizations have had an analytics department at this point for five-to-10 years, a lot of the big decisions in how they are going to do analytics, and how analytics are going to be integrated into their processes, are largely already made," Moore said.

"(Analytics) has also kind of become relied upon for things that are not research. They are providing advance-scouting reports to the coaching staff before games, or they are providing amateur scouting help around draft time. These tasks take up almost all the time and energy that you thought you were going to be able to use for innovative, cool stuff."

Moore wanted to work on big projects. He wanted to ask big questions of datasets and find interesting conclusions. But he learned that wasn't likely to be a primary task. Moore heard similar stories from friends working within departments of other organizations.

After his internship with the Twins, he was able to land his dream job as a full-time analyst with the Rockies. He wanted to move to Denver, and he also wanted to be part of a smaller analytics team, which he thought would allow him to make more of an impact.

"Every other team has this big bureaucracy built up within analytics," he said.

Instead of working on big projects, he was making heat maps.

"This is maybe a me problem, but I just couldn't believe that a lot of the work the analytics departments were working on was actually helping the team win more games," Moore said. "We're giving them, like, 300 heat maps before every game. How is that helping us win?"

Sitting at his cubicle in Denver during the 2021-22 offseason, he came to a realization.

"It was just kind of this feeling of, 'This isn't it,'" Moore said. "I got to where I wanted to get to, and it doesn't feel like I wanted it to feel."

It wasn't about the money, though it's generally not great for entry-level types, either. Because there's so much interest in working in baseball, teams can pay their staff lower wages compared to other industries where they could apply their skills.

Career doubts started to enter Moore's mind in Minnesota, and he began meeting with a therapist to talk through what he was feeling. Something was missing. He likes to talk things out, and share, which he does through blogging about his experience.

"I just became really fascinated with, 'I don't even really know what is driving me and what is important to me?'" Moore said. "There is some stigma around (therapy), and I kinda don't understand why. The most important thing was thinking about values - what is it that you actually care about? What is it that you value? That's something I had never actually thought about."

He liked that friends and family thought he had a great job, but beyond that, what else did he value?

"At the time, all I really cared about was being recognized for the work I was doing," he said. "I learned that that's not healthy: external validation. It wasn't 100% external validation, working in baseball, but it was a big part of it. Prestige, too. If you get this job that everyone wants and is impressive to your family and family's friends, you feel better about yourself.

"But you kind of sit there and think, 'Do I want to spend basically all of my waking hours thinking about ways to get people to listen to my ideas?' I thought that job satisfaction would equal life satisfaction. As soon as I started breaking that down, it was just like, 'Who am I outside of that?' That's kind of what I have been working on since."

In spring 2022, the Rockies fired the department head who hired Moore, which was a disappointment, and they also asked him to stay in the office for all home games in addition to his 9-to-5 shift.

Working long hours is fairly common in the industry. For some, the trade-off's worth it. But Moore wanted more time outside of the office and away from work. He felt his relationships outside of baseball were lacking. He left in April 2022 and now does data science work for Nike. He's happy with his choice.

"Curiosity that used to be about baseball, now I wonder about myself," he said, "I am grateful that I was confronted so early with this. A lot of people encounter that later. It's kind of like that idea of a midlife crisis. That always terrified me, that idea of, 'Those last 50 years - we are going to throw those out the window and start over.'"

Moore made the bold step to walk away from what he'd worked toward since high school. It takes courage to step away from such a personal investment. It also takes courage to take that first step as a job seeker at an industry convention. It's all part of chasing your dream.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.