Baseball's beanball death, 103 years ago, changed the game forever

The mid-August day in upper Manhattan was hazy and humid with intermittent light rain. Some of those present said there was a yellowish tint to the air. In the fifth inning of the game, as the afternoon lengthened following a 3 p.m. first pitch, the ball was filthy, coated with dirt and tobacco juice. It was almost certainly scuffed, too. Many suspected all those elements conspired to make the pitch difficult for a batter to see out of Carl Mays' hand.

The Polo Grounds was also an oddly shaped ballpark, pieced together through multiple iterations. The 1920 version featured wooden bleachers that wrapped around the entire outfield. There was no batter's eye, so it's possible clothing worn by some fans situated in the center-field bleachers for the game between the Cleveland Indians and New York Yankees made picking up the ball even more difficult.

In this deadly calculus was also the pitcher, the Yankees' Mays, who featured a sidearm delivery, and who had a reputation for being aggressive on the inside part of the plate.

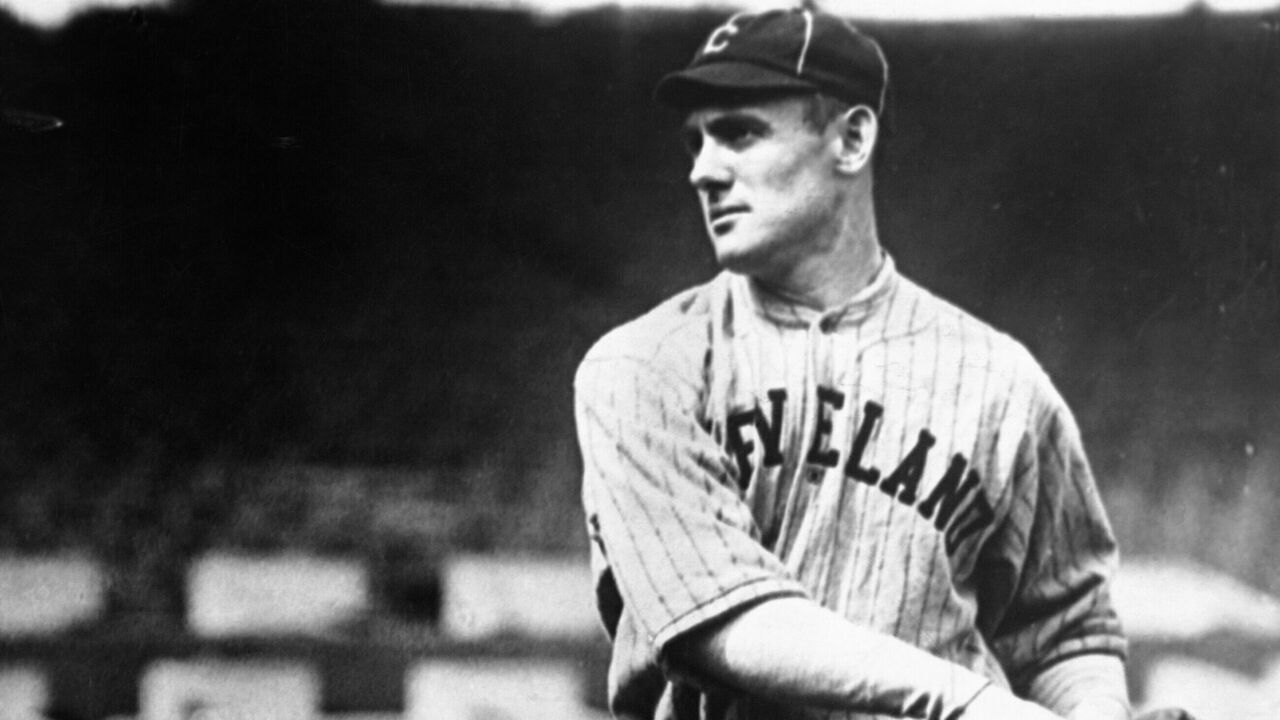

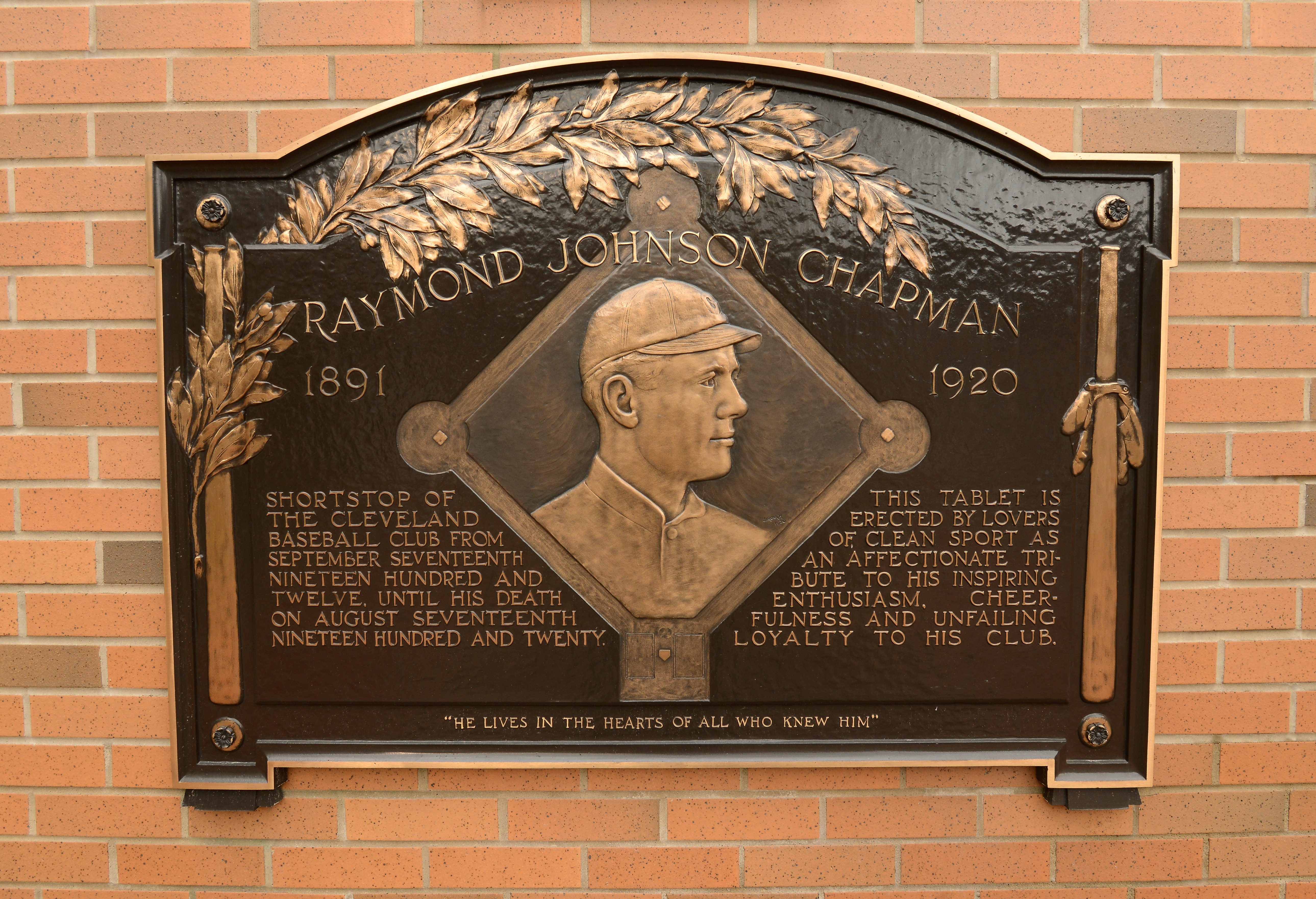

This perfect, terrible storm of circumstances on the afternoon of Aug. 16, 1920, led to the death of 29-year-old Cleveland shortstop Ray Chapman, the only fatality related to on-field events in major-league history.

Chapman, a right-handed batter hitting .303 who regularly slotted into the No. 2 hole ahead of star player-manager Tris Speaker, led off the top of the fifth inning. He didn't seem to see the first pitch, which struck him near his left temple. Initially, the ball's collision sounded to some like it hit the bat. The ball rebounded partway back to the mound, and Mays fielded it, believing it had hit the knob of the bat. Chapman crumpled to the ground. He died early the next day.

From the Cleveland Plain Dealer's Tuesday morning edition on Aug. 17, 1920:

He sank to the ground and Umpire Tom Connolly turned at once to the stand (sic) and called for a physician. Two responded and the players of both clubs rushed to the plate. After a few minutes, Chapman regained consciousness and was assisted to his feet. He tried to talk but found it impossible. The blow evidently caused a temporary paralysis of the vocal nerves. After a short delay, Chapman was held up by a Cleveland player on either side, and started for the club house (situated behind center field). He walked all the way across the infield and then it appeared that his legs gave way and the remainder of the route was covered with the injured player resting in the arms of team mates (sic).

Over 100 years later, Chapman's death still echoes around baseball. It marked the end of one era and was a tragic catalyst to the creation of the modern game.

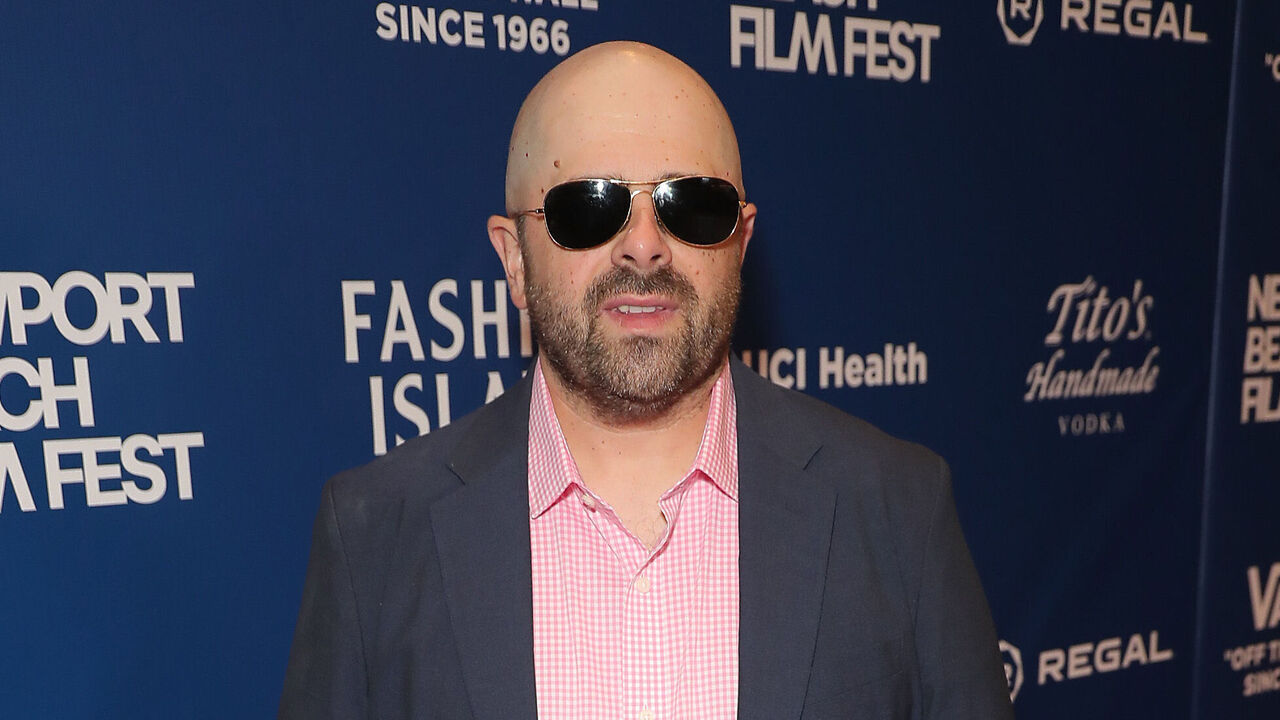

Filmmaker Andy Billman chronicled Chapman's death in his 2022 documentary, "War on the Diamond."

As a native Clevelander, Billman wondered why the city felt such a deep rivalry with New York's American League team. After all, the Yankees and their fan base never considered Cleveland much of a rival. The Yankees won 25 World Series titles in the 20th century; Cleveland won two.

His research led him to Chapman's death as the root cause.

"This is a time period of no trainers. They did not properly ice him," Billman said. "They did not properly treat him. Medicine is not like it is 100 years later. The umpire really did yell into the stands, calling out, 'Is there a doctor in the house?!'"

Some reports said Chapman was able to speak as he was helped to his feet, telling teammates before losing consciousness: "I'm all right; tell Mays not to worry … Ring … Katie's ring." He was recently married.

He was taken by ambulance to St. Lawrence Hospital, a half-mile from Polo Grounds, where he was examined.

The game continued, with Cleveland holding on to win 4-3.

Late that afternoon, an urgent telegram was sent to Chapman's wife in Cleveland. The Plain Dealer reported that Speaker reached her by "long-distance telephone," as well. He recommended she travel to New York "because he feared developments might make her presence here advisable."

We can only imagine the terrified state she was in as she took an overnight train to New York, which was about a 12-hour journey in the 1920s.

Still, the Aug. 17 morning newspaper reported there was growing optimism for a time after the game. Speaker said Chapman regained consciousness at the hospital.

"I was badly scared when I saw Ray try to talk this afternoon but he was (able) to talk tonight," Speaker told the newspaper. "So that worry is over. I am inclined to believe that if there is a fracture it is not a severe one."

But by the time those picking up the morning edition were reading the article, Chapman was dead.

His condition worsened into the night, and a decision to operate was made by Dr. T.M. Merrigan. According to The New York Times' account, the operation began at 12:30 a.m. and was completed at 1:44 a.m. Merrigan found that the pitch caused a depressed fracture spanning three inches.

From the Times report:

Dr. Merrigan removed a piece of skull about an inch and a half square and found the brain had been so severely jarred that blood clots had formed. The shock of the blow had lacerated the brain not only on the left side of the head where the ball struck but also on the right side where the shock of the blow had forced the brain against the skull.

Speaker was stricken with grief and guilt when he met Katie at Grand Central Station that morning and delivered the news. Speaker had convinced Chapman to come back for another year after the star shortstop considered retiring following the 1919 season. Speaker believed they could win the World Series.

Katie, pregnant with the couple's first child, was so distraught she had to be sedated.

"For a guy to die, for his wife - back in the time of Western Union telegrams - for her to get a telegram like that out of nowhere, and take a train into Grand Central not knowing if her husband passed away or not ... that's hard," Billman said. "You finally arrive in New York hearing or thinking he's OK, and as soon as you arrive in New York, you don't even get a chance to say goodbye. That's awful. And Speaker had to tell her. He was also (Chapman's) best friend, and he was also the reason he came back."

The tragic events for the Chapman family didn't end there. Katie remarried a wealthy businessman and moved to Los Angeles, but suffered from depression. She died by suicide in 1928 at the age of 34. Their daughter, Rae, died from measles the following year.

In the Aug. 18 morning edition of the Plain Dealer, a seven-column headline ran across the front page: "Chapman's Body Arrives Home Today."

Speaker traveled back to Cleveland that day along with Katie Chapman, her brother, and Cleveland pitcher Joe Wood. The game was canceled. The Plain Dealer also reported on the scene at the Ansonia Hotel in New York:

At the local headquarters of the Cleveland club, the depression is pronounced. There one may see ballplayers walking idly through the corridors, their every action indicating they are unable to realize their pal and teammate is no more.

Another story in the same edition reported:

Wherever baseball is discussed, there were long faces and tears as the news was spread. Hundreds - no thousands - refused to believe the rumors on the street. They called up the newspaper offices seeking confirmation and even then they hesitated to accept the announcement as truth.

Chapman's funeral took place Aug. 19 at St. John's Cathedral in Cleveland. The club returned for the service. Thousands attended.

And another 15,000 crowded League Park and stood in silence, caps removed, for a memorial service when the club returned from its road trip. A bugler from the Cleveland naval reserves, of which Chapman was a member during World War I, played the calls "Colors" and "Retreat" before the game.

Remarkably, less than two months later at League Park, Cleveland went on to win the World Series over Brooklyn.

Almost immediately that August, disbelief was replaced by rage toward Mays.

Mays already had a reputation for pitching too aggressively. He led the AL with 14 hit batters in 1917, and hit 34 total batters in the three previous seasons.

He wasn't particularly well-liked, either. He was a loner, known for his taciturn nature. He was involved in his fair share of brawls. But this was an accident and Mays was contrite.

After the fateful game, Mays sat at his locker distraught, head in hands, according to his biography by Kenneth D. Richard for the Society for American Baseball Research. "I would give anything if I could undo what has happened," Mays was quoted.

From the Plain Dealer's reporting:

According to Mays, the ball which hit Chapman was a 'sailer,' or a fast ball (sic) which takes a peculiar twist … when the cover is rough. Chapman was the first hitter in the inning and there was no reason for a 'bean ball' of which pitchers are accused at times. Chapman did not try to duck away from a close ball, but appeared to have been fooled when the ball broke toward him. He did not move.

Speaker told reporters he didn't hold Mays responsible "in any way," but by then it was too late.

Boston Red Sox and Detroit Tigers players asked AL president Ban Johnson to bar Mays from pitching.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, an umpire claimed no pitcher "resorted to trickery more than Carl Mays in attempting to rough a ball in order to get a break on it which would make it more difficult to hit."

"The other half of the story is that Mays' life changed forever, too," Billman said. "Some of it was very unfair. He was called a murderer. He was ostracized."

Mays didn't pitch for a week but he returned with a 10-inning shutout on Aug. 23.

Mays didn't make the team's trip to Cleveland in September. "We are not taking Mays to Cleveland not because we think there is danger of any trouble but out of respect to the feelings of the people there," Yankees co-owner Tillinghast L'Hommedieu Huston said. "It's largely a matter of sentiment."

In addition to the individual impacts, the accident was also a turning point for the major leagues, Billman said. It helped bring to an end the dead-ball era.

Before the 1920 season, spitballs were banned, but with a limited number of pitchers grandfathered in. After the Chapman incident, balls were replaced more often during games so cleaner balls could more easily be picked up by the batter. There was no overhaul to the manufacturing process of the ball, which had its core changed to cork from rubber years earlier.

The emergence of Babe Ruth and home runs are tied to the so-called lively ball era. Ruth was in right field when Mays hit Chapman. On Aug. 19, Ruth hit his 43rd home run of the season, having long surpassed his own single-season home-run record set a year earlier (29).

The rule changes cleaned up play and made baseball safer, and were accelerated by Chapman's death. "This incident changed a lot of things in people's mindsets," Billman said.

"It was a brutal game. It was not a game for weak people," Billman said of the dead-ball era. "It was a very rough-and-tumble game. It was kind of more like the Wild West. Once Babe Ruth and the Yankees took over in 1921, it became a game we are more used to where it is focused on heroes, stylized, and charming."

Batting helmets didn't catch on right away, although experiments began in various quarters, including by Chapman's Cleveland teammates. It wasn't until the 1940s that they came into any real use and it wasn't until 1971 that modern helmets became mandatory in both leagues. The last grandfathered player to step to the plate without a helmet did so in 1979.

Today, Chapman is largely a forgotten figure. But that one pitch, that one tragic afternoon 103 years ago this week, helped usher in a safer, more modern game, more like the one we know today.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.

HEADLINES

- Yankees score 15 vs. Brewers in consecutive games to win series

- Crew chief: Judge should've been called for interference on slide during rally

- Twins win 7th straight with rout of struggling Angels

- Tucker leads Astros to second win over Rockies in Mexico City

- MLB's most unlikely breakout, 8 more observations