Ohtani is amazing, but here's one way the Angels could maximize his gifts

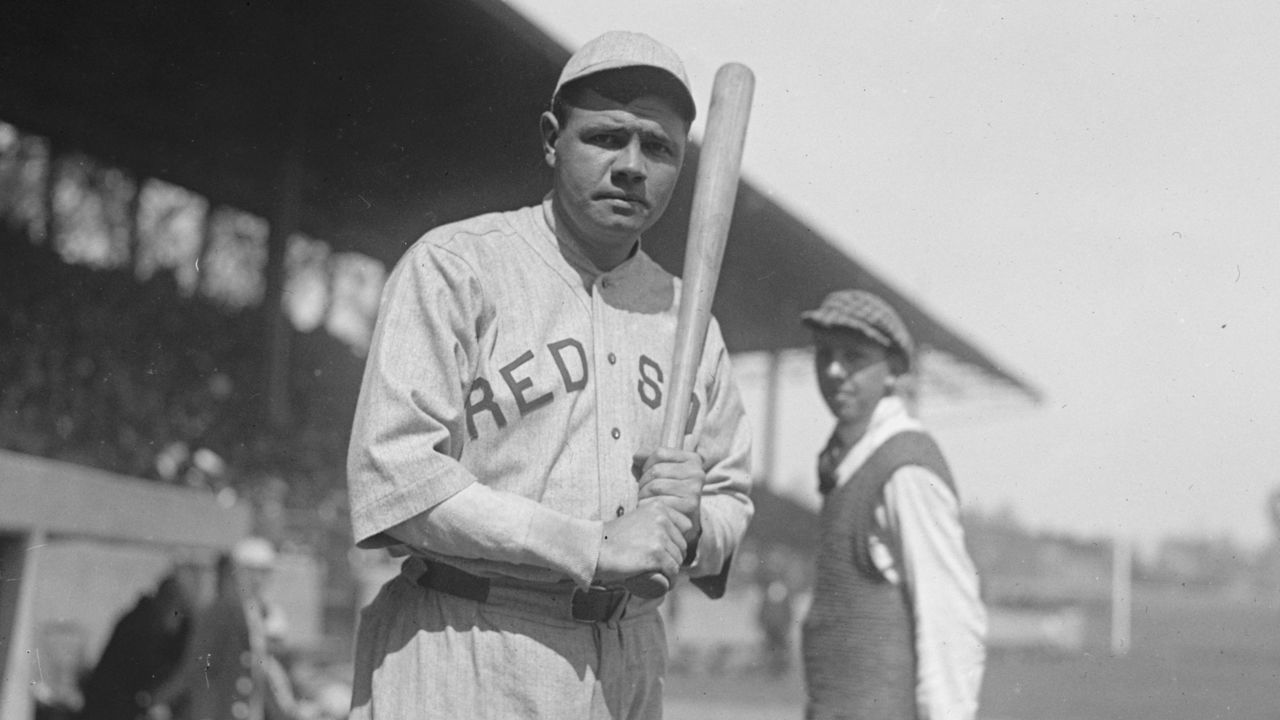

For three days in January 1920, New York Yankees manager Miller Huggins scoured Los Angeles for Babe Ruth. He'd traveled there to inform the former Red Sox two-way star that he was now a Yankee, acquired from Boston owner Harry Frazee for $125,000. Huggins finally found Ruth on a golf course in Griffith Park where Ruth played regularly to stay in shape, in addition to his regular "long walks," according to The New York Times account of the search. Huggins cornered Ruth at the end of a round.

As more details trickled in about the greatest player acquisition of all time, a few things emerged: Ruth had no love lost for Frazee, who branded him a troublemaker - "Frazee is not good enough to own any ball club," he said - and Ruth wasn't going to continue to pitch.

As Ruth began to show a rare ability to smash a baseball with an unorthodox swing in 1918, The Boston Globe reported, "Ruth's big ambition is to be an everyday member of the ball club." Ruth combined for 6.7 fWAR in 1918 (5.2 as a batter). He then clubbed a record 29 home runs in 1919. But the Red Sox wanted him to keep pitching, too. Ruth was regarded as one of the best left-handed pitchers in the game, but his interest in pitching was waning. The Yankees wanted his bat.

After acquiring Ruth, they secured a $150,000 insurance policy on the slugger that "made provisions for any accident serious enough to keep the home-run king out of the daily lineup," the Times reported.

Ruth told the press he would smash his own home run record in 1920 - and he did with 54 homers - in part because of the short distance to the right-field wall at Polo Grounds where the Yankees then played. He would pitch only five more times in his career.

"I don't think a man can pitch in his regular turn, and play some other positions and keep the pace year after year," Ruth said.

The year marked the end of the last great two-way player experiment until Shohei Ohtani came along. The big question with Ohtani is how to balance his hitting and pitching to maximize his skill set and keep him on the field. This season, the Los Angeles Angels are much more aggressive in how they deploy him - to the delight of all of us watching.

But is this role too much? Can he sustain this year after year? Many doubt it, including Ruth in speaking of such a role a century earlier. Ohtani's already had one Tommy John surgery and other minor pitching-related ailments. He wants to pitch and hit, but he's been a better hitter throughout his career.

Perhaps there is a more sustainable way to employ him without giving up on his two-way status: Ohtani as a DH/closer.

A day after tying for the major-league lead with his 12th homer, a two-run, go-ahead shot off of Red Sox closer Matt Barnes on Sunday, Ohtani launched a laser into the right-field seats against Cleveland on Monday to take sole possession of the home run lead. He added No. 14 on Tuesday.

“Ohtani is the most physically gifted player I have ever seen,” Barnes said Sunday.

How good could Ohtani's bat be if he gave it even more attention? Including his professional career in Japan, Ohtani has made 2,280 plate appearances and faced 2,524 batters as a pitcher. For his career as a hitter in the NPB, he posted a career weighted runs created (wRC+) mark of 141, according to the Japanese baseball analytics site DeltaGraphs. That means, adjusted for yearly run-scoring environments and ballparks, he was 41% better than the average NPB batter. As a pitcher? He was very good, posting an adjusted fielding independent pitching mark (FIP-) of 70, or 30% better than league average.

Based on those metrics, his hitting outperformed his pitching.

In the major leagues, he's posted a wRC+ of 130 and a FIP- mark of 90. Again, that means he's been 30% better than average MLB hitting production, and 10% better than the average pitcher. While Baseball-Reference.com values his hitting and pitching nearly equally this year, FanGraphs places double the value on his batting performance to date (1.5 fWAR hitting versus 0.5 fWAR pitching).

So, after the combined equivalent of nearly four full professional seasons as a batter and 622 innings as a pitcher, Ohtani's track record suggests he's a better hitter than a pitcher - and that's significant because he boasts a 2.10 ERA this season heading into his scheduled start Wednesday.

Ohtani's bat, however, is also getting better this season.

Early on, Ohtani set a new career high in maximum exit velocity (119 mph), which trails only Giancarlo Stanton (120.1). It's also the top max exit velocity for any left-handed hitter in the Statcast era.

This year, Ohtani owns a career-best rate in average launch angle (17.3 degrees), which means he's more often in the sweet spot for lifting the ball and tapping into his power. He's first in the majors in barrel rate (13.3%). He could be a 50-homer threat with 600-plus plate appearances. While his plate discipline isn't Bondsian, he might be the rare player who can be an effective bad-ball hitter - he's seventh in the game in slugging on pitches just off the plate or on the edge of the strike zone.

Shohei Ohtani, master of adjustability. #Angels pic.twitter.com/DKA300RuC5

— Lance Brozdowski (@LanceBroz) May 18, 2021

Moreover, his elite running speed adds to his advantage as a hitter, as he makes routine ground balls dramatic events. He's already legged out eight infield hits this season, ranking fifth in the majors. He's stolen six bases. His ceiling might be of a player who could hit 50 home runs, steal 30 bases, and rack up huge run totals by taking extra bases with Mike Trout and Anthony Rendon hitting behind him.

While his skills as a batter are actually showing signs of growth, his pitching skills are very good but stagnant in some notable areas.

Ohtani's average fastball velocity (96.7 mph) is above the major-league average (93.6), but it's also the same as his peak level in Japan, when he averaged 96.6 mph in 2017. Velocity typically begins to decline with age, and since the 26-year-old made the jump across the Pacific, MLB fastball velocity keeps increasing relative to Ohtani's rate.

Command is perhaps the most difficult skill to improve on the mound. In Japan, Ohtani posted a walk rate of 9.1%, and he's at 14.8% for his major-league career. (The MLB average is 9% this season). His career K-BB% rate was 19.4% in Japan and is 16.6% in the majors. It's a good but not exceptional rate. And it's that lack of precise command that could hold Ohtani back from becoming an elite ace, though perhaps it'll improve the further removed he is from Tommy John surgery.

But with Ohtani's desire to pitch, the rarity of his arm skills, and the Angels' dearth of quality pitching, there is perhaps a better role that would allow him to unlock as much potential as possible in both areas: to become a late-inning arm instead of a starter.

An end-of-game bullpen role could allow Ohtani’s pitching skills to play up and it could shield his uneven command.

The average fastball velocity of starters who move to the bullpen often increases. If Ohtani could sit at 98-99 mph instead of 96-97, his walk rate could be reduced if hitters had a bit less time to react. He could also heavily rely on his split-finger pitch, one of the best swing-and-miss pitches in the game. His elite strikeout rate could spike higher. He could be the top closer in baseball. And in pitching fewer innings, perhaps he could reduce injury risk.

If one was drawing up the ultimate player, it might be one who can help his team get ahead with his bat early in games and then preserve a lead late with his arm. By using Ohtani in only late, higher-leverage situations, he could have more impact per inning. Relievers often rate highly in the win-probability added metric, since performance in close, late games typically influences game outcomes more than pitches thrown earlier in a contest.

The big issue with using Ohtani as a reliever is that the Angels would lose their DH when he stepped on the mound. But if Ohtani was being used only in the later innings when the Angels held a lead, it would be less of an issue.

There really are no historical comps for such a role in the majors. In 2001, Kent State's John Van Benschoten led Division I in home runs and also saved eight games. His arm was good enough that the Pittsburgh Pirates drafted him eighth overall that year and had him focus only on pitching. Injuries derailed his career, though.

A DH/closer role could allow Ohtani to maximize his bat-missing ability on the mound - and shield command issues - and allow him to reach his offensive ceiling. He could be more rested overall and give more time to offensive preparation. More than anything, it might make his desire to remain a two-way player sustainable.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer.