Film Room: Can the Patriots block Michael Bennett and the Seahawks?

Nate Solder still sees shades of blue and gray.

Three years ago, Solder and New England Patriots teammates Dan Connolly and Sebastian Vollmer were thumped in Super Bowl 46 by the New York Giants' defensive line.

Solder, who was a rookie splitting snaps with Vollmer, was tugged around. He overextended his frame, lunged and had his long arms batted away to the tune of four hurries allowed. Connolly wasn’t much better as a cleanup center, allowing two hurries. And Vollmer, the German with long arms and great power, was slapped around by multiple Giant rushers for six hurries allowed and a safety on the Patriots’ first play. The three couldn’t keep their legendary quarterback, Tom Brady, the Juan Roman Riquelme of American football, upright all game.

The speed rushes and power rushes are still there. The blue and gray, too. They’re inescapable. The three Patriots are back in the Super Bowl, this time Super Bowl 49, and they’re facing a similar defense to the Giants’.

The Seattle Seahawks’ defense is loaded with those same kind of rushers. They’re versatile, athletic, explosive technicians. They pride themselves on cohesively sacking quarterbacks.

Cliff Avril

Look beyond Avril's five regular-season sacks. He’s much more than a simple sack total; he’s an all-around disruptor.

In 2014, he had 46 hurries, according to Pro Football Focus, second-most among 4-3 defensive ends. He tore through backfields and threw down quarterbacks. He did it with speed and power and with technique. His handwork is some of the best in the NFL.

He is primarily a weak-side “Leo” in the Seahawks' scheme, where he’s racked up seven hurries and two sacks this postseason.

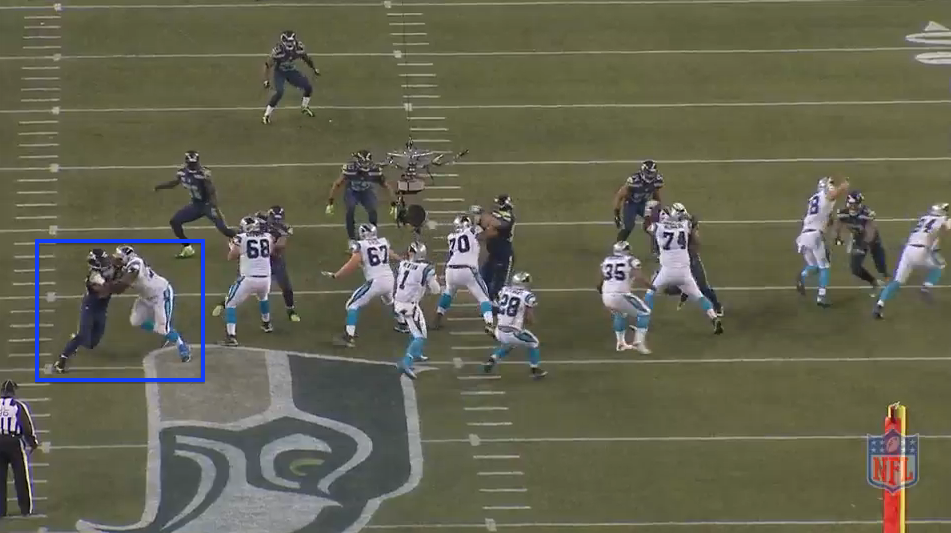

On one play against the Carolina Panthers in the divisional round, Avril lined up at weak-side end in the Seahawks’ 4-3 Under front. He was at the five technique when he raced three steps forward and was bearhugged by the left tackle.

The tackle hung his plump arms off of Avril’s shoulders and tried to anchor. Avril pumped his hands into the tackle’s open chest and took another step outside to build momentum. Then he sunk his hips and his left knee and stretched his right leg to power up and toss the tackle aside.

The tackle lost his balance and suddenly faced downfield. He and the left guard, who chipped in at the last second, grabbed Avril's arms to hold him captive. Avril powered through, though, and burst into the backfield to sack the quarterback.

Bruce Irvin

Irvin wasn’t always supposed to be an outside linebacker, no. He came in as a defensive end, a pass-rush specialist who wasn’t big enough nor strong enough to consistently defend the run.

To absolve Irvin of direct contact with blockers, the Seahawks moved him to outside linebacker on the first two downs and made him a pass rusher on the third. Sometimes he would stick his hand in the turf, other times he would rush from linebacker.

This season, Irvin racked up 6.5 sacks as well as five hurries and one sack in the playoffs. Like Avril, he teed off on the Panthers.

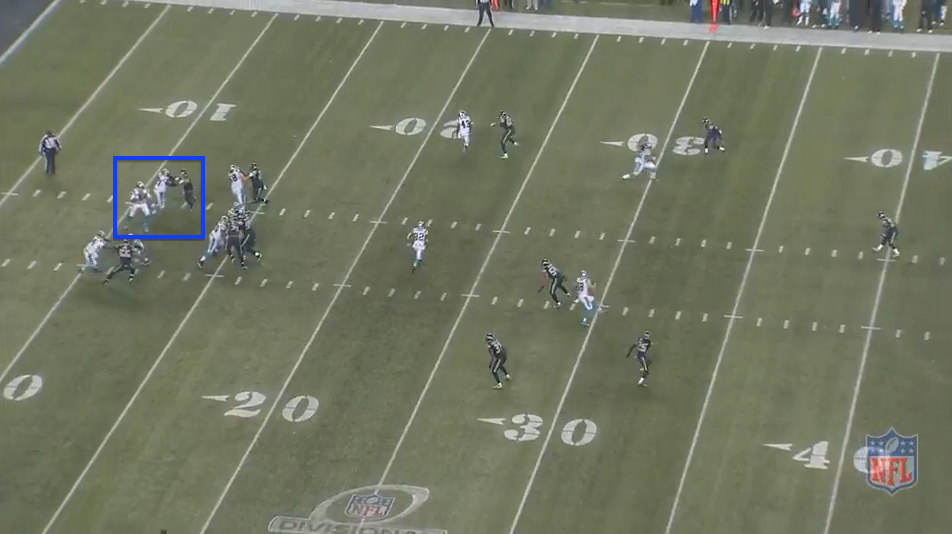

His sack came early in the fourth quarter. An obvious mismatch in quickness, Irvin shot forward from the weak-side 3-4 outside linebacker position against the same left tackle. He rushed straight outside and forced the tackle to kick-slide longer than he should have.

The tackle abandoned the entire inside gap. He turned his back to the quarterback and slid his feet all the way out.

Irvin stuck his left foot inside, then his right foot outside and pinned the tackle onto his heels. When the two collided, Irvin shoved him to his right as he rushed inside to his left. He swallowed the quarterback for his only sack of the playoffs thus far.

Michael Bennett

Bennett is the one to be concerned about. He is the one who floods back bad memories of that championship game against the Giants. The one who is reminiscent of and capable of doing damage like Justin Tuck did.

Like Tuck, Bennett is a versatile pass rusher who primarily plays left defensive end on the strong side. He’s athletic, quick and physical, able to weave his way through seams that initially seem slammed shut.

On passing downs, Bennett kicks inside to defensive tackle. He terrorizes guards who are too weak and too slow to compete with him. His inside rush opens up the outside rush for his teammates, too, because of the attention he draws.

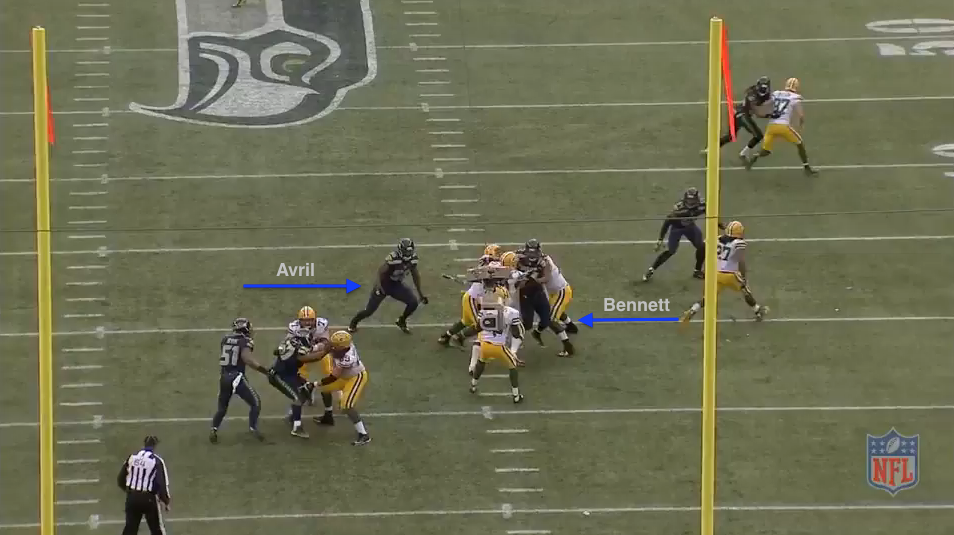

Against the Green Bay Packers in the NFC Championship, Bennett lined up across the right tackle on third-and-8. He was considered the defensive tackle, but he was essentially an extra end because of his head-up, four-technique alignment. The other end, Avril, was outside of him in a wide-five technique.

Because of the alignment, the Packers’ right guard and right tackle were forced to slide to their right. That instantly stretched the gaps to the inside of them.

Once Bennett saw the A-gap widen between the right guard and the center, he raced across the guard into the gap. That drew the attention of the center and when Avril looped behind Bennett into the opposite A-gap, Bennett drew the right tackle, too.

No one blocked Avril, which allowed him to twist the quarterback down for a sack.

Bennett’s four-technique alignment could be problematic for the Patriots because their offensive guards do not move as well laterally as they do forward and backward. The stacked look from Bennett (with Avril or possibly Irvin next to him) may be used on the right side of the defensive line, where Dan Connolly lines up at left guard.

Dan Connolly

Connolly isn’t the player he once was. Granted, he hasn’t ever been known for magnificent athleticism and quickness. What he is known for is his intelligence and awareness.

He’s bounced between both guard positions and the center position over the years. He’s a grinder, a blue-collar worker who drives back defensive linemen with every ounce of him. He sees what defensive linemen will do before they’ve decided to do it, which allows him to set his feet and his hands to beat stunting linemen to the point of attack.

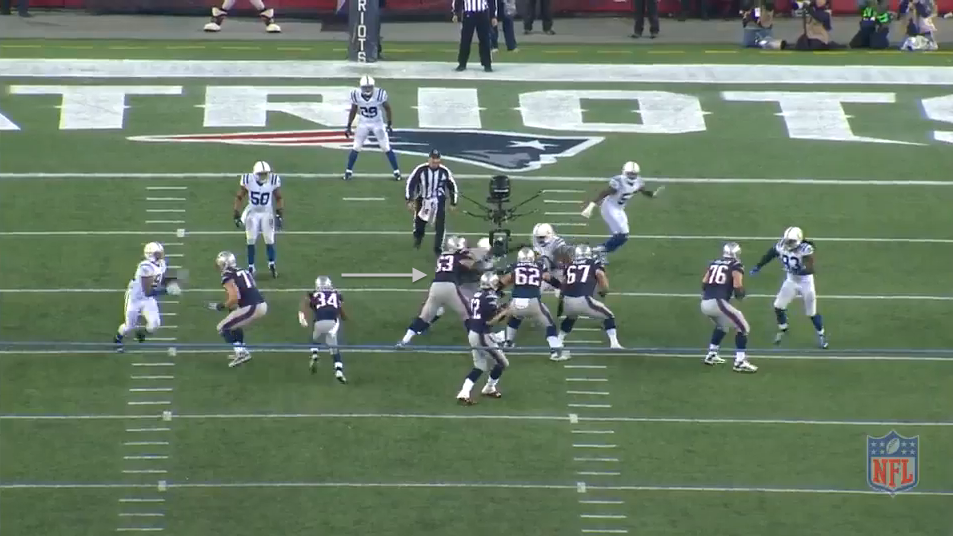

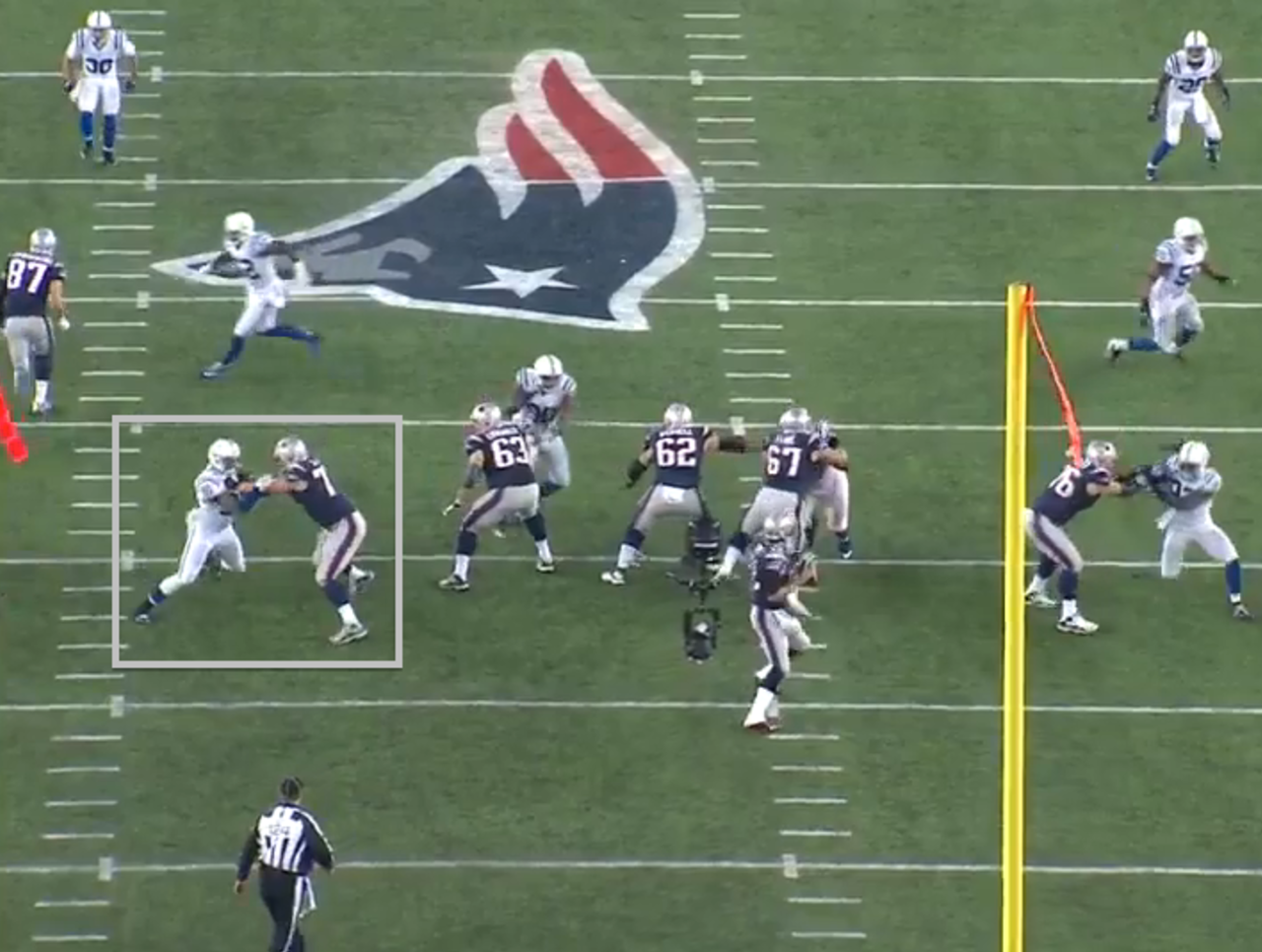

In the AFC Championship game against the Indianapolis Colts, Connolly was lined up in a two-point stance. In front of him, a Colts defensive tackle was in a three-point stance. The Colts had an even front with two defensive tackles that plugged up both guards and left the center uncovered.

When the play began, the defensive tackle in front of Connolly jumped into the A-gap to the inside of him, which forced the veteran guard to slide to his right and slap the defensive tackle to the ground to pass him off to the center and right guard.

Simultaneously, the other defensive tackle hustled across the line and toward Connolly. Connolly saw him and waited, then clubbed and hooked him long enough to buy Brady time to throw the ball.

Sebastian Vollmer

Vollmer is the best Patriots offensive lineman. He is their most consistent. He is the type of tackle who doesn’t hide from any challenge. He’s strong, quick, long and heavy.

He is a laid back, 6-foot-8 blocker who lets rushers come to him. He has a tactical, calculated discipline in his every move, true to his German nature. Once rushers come to him, he relies on his 33 ¼-inch arms and Hulk-like strength to ride them wide of the pocket.

Vollmer has relied on these strengths to have a strong regular season and playoffs. He’s pass blocked well, according to Pro Football Focus, allowing a total of four sacks and 22 hurries.

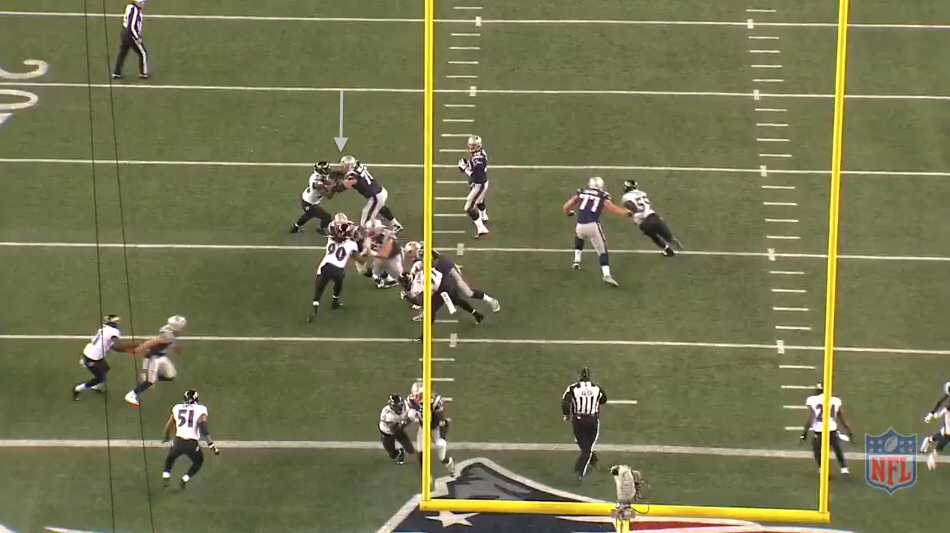

On third-and-4 in the divisional round against the Baltimore Ravens, Vollmer hurried out from a two-point stance to combat the outside linebacker’s speed rush. The linebacker tried to get to the corner and then thrust his hands into Vollmer’s chest before the tackle was ready.

With surprise, the linebacker lodged his hands into Vollmer’s chest, but he couldn’t move the gigantic blocker. Vollmer, whose hands were initially down as he waited for the rush, drilled his hands into the linebacker’s chest. Then he pressed the linebacker back and anchored down, quelling the rush for good.

Nate Solder

While Vollmer has buried rushers this season, Solder has been inconsistent. His technique has been up-and-down, as he has lunged to make blocks. He also has dropped his head, at times, which makes him lose sight of his rusher and of his own position.

He’s bounced back in the playoffs, however. He’s only allowed a sack and three hurries in two games, according to Pro Football Focus, and been solid with his technique. He hasn’t allowed rushers into his chest as much as before and when he has, he’s bent his knees and used his punch and his frame to anchor.

On a second-and-6 against the Colts, Solder kick-slid with his hands up from a two-point stance. His knees were bent, his rear was out. He waited and watched the delayed rush of a Colts linebacker.

The linebacker took a couple steps forward and shook his shoulders. He tried to set up an outside rush with hesitation, but it wasn’t going anywhere. Neither was Solder, who had enough.

Solder sunk his feet and hammered the linebacker’s heart with two jabs. His arms were fully extended. Then he latched onto the linebacker and drove him wide of the pocket, allowing his quarterback to step up.

That’ll be the question that needs to be answered in Super Bowl XLIX. Can Solder and his teammates keep Brady upright? They struggled against the Giants three years ago and these Seahawks are built the same way.

All three rushers – Avril, Irvin and Bennett – could pose problems for Solder if they line up across from him. Irvin’s quickness could lead to Solder’s hands being slapped away time after time. Avril’s power and hand usage could expose Solder’s chest. Bennett could line up over Solder and then force Connolly (or another guard) to slide around more than he should and leave the interior gaps vacant.

That’s where Brady is most vulnerable. That’s where the Giants ate up the Patriots and where the Seahawks will try to do the same.

All statistics referenced are courtesy of ProFootballFocus.com.